Indians are schooled and indeed colleged to always see literature and science as two neatly segregated worlds that orbit on eternally parallel paths. This is a global condition, but in India, the divorce of arts from the sciences is so complete that most writers who write about STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) do not even try to reach out to readers who are not inclined to matters scientific.

Therefore, when the worlds of science and literature do collide, the big bang that does result is unvaryingly magnificent. For our generation of readers, Stephen Hawking achieved this rare feat. He attempted to write an all-encompassing, lucid and accessible book that eschewed equations and opaque theory. A Brief History Of Time was a book everybody read because it transcended the world of science to become a meditation on existence, transience and the meaning of life — in other words, it was a literary classic.

One can ponder on whether it was the specific nature of the author’s condition, along with the heroism needed to write and reach out, that made Hawking the colossus he was. However, that would be doing a disservice to his life’s work, and more critically to his books. There is so much wisdom in Hawking’s writings, which extends beyond the purview of science, making his books the classics that even those who are terrified of all things STEM can possibly read.

As Hawking moves to the great blue yonder (a theory he energetically dismissed in his lifetime), it would be instructive to hark back to books about science that boasted flawless prose, deep thought and the ability to compel the reader to turn the page. Hawking would lead that list, but there are others who made science palatable and readable to even those who were steadfastly ‘arts type’.

Bibliopath would like to make full disclosure that science is not her cup of tea. She has not read extensively on the subject and has a low threshold of tolerance for science jargon. However, that these books did not fly out of the window to form a parabola is testimony to their being completely readable.

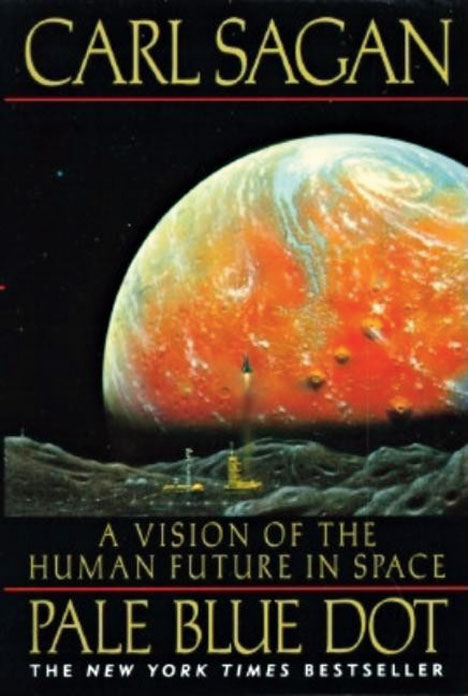

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan

I do not know whether this book makes sense anymore because interest in space travel today is more about tourism and less about the question of ‘is there anybody out there’. Today, we hear about Elon Musk planning SpaceX to take us out to space for a jaunt, but Pale Blue Dot harks back to a time when space was both forbidding and also infinitely fascinating.

The book possibly emanated from a speech Sagan made where he referred to earth as nothing more than a “pale blue dot” which should not see itself as the centre of the universe. The book discusses space programmes that were at the cutting edge of space research at the time, and even explores the possibility of life on each of the planets. Sagan goes a step further to explore whether earthlings aka human beings could go and colonise other planets.

The underlying passion for pushing the frontiers of astronomy and also to drive home the need for peace both make the book a more serious and sobering work when compared to Sagan’s Cosmos. The latter was published after the stellar success of the television series by the same name.

The Preserving Machine by Philip K. Dick

Some of the greatest writing on science is in fictional form with the genre boasting of maestros like HG Wells, Jules Verne and Ursula le Guin. These dreamers would be delighted to know that several of their fantasies are now part of our lives and the old cliche that it has to be dreamt for it to happen is apt for these wonderful writers.

However, the dark, dystopian voice of Philip K. Dick is one that sets him apart in the sci-fi genre. Millennial, this is the man who wrote Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep, the book on which Blade Runner version 1982 was based. Dick’s books are set in the future or in other places, aka, universes.

The Preserving Machine is wonderful because it is a collection of short stories that sock you in the gut in different ways. A scientist trying to preserve the symphonies of Brahms and Mozart comes to a disturbing and unusual discovery, while a prosaic scientist becomes the wub (a Martian pachyderm) he eats. These are stories that seem troubling and relevant even today, and would certainly appeal to readers who like their fiction to be black and unsweet.

A Brief History Of Time by Stephen Hawking

The book was published on April 1 thirty years ago and has sold millions of copies in several languages across the world. From Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity to the Big Bang Theory, to indeed the limitations of science, Hawking presents difficult, complex theories in crystal clear prose. The tone is friendly, and even when scientific jargon is used, a little dry humour always makes one wade through it cheerfully. The book was written with the express aim of providing an overview of the question: How did the earth come to be? Hawking then traverses various theories about natural phenomena and also the future of the universe.

Periodically updated over the last three decades, Hawking added a delectable foreword sometime in the 1990s, but the original foreword by Carl Sagan is wonderful for the way it details Sagan’s first encounter with Hawking.

There are parts of the book that are heavy going, even though there is just one equation (e=mc2) in the whole book. One could skip those to focus on the author’s meditation on God’s role in the creation of the universe. It is interesting to note that he uses upper case always even as he strenuously contends that He did not have much to do. Hawking claims the chain of events set off by the Big Bang Theory would have led to the creation of the universe anyway.

The Gene by Siddhartha Mukherjee

Few contemporary writers can write as beautifully as Mukherjee. His gifts of language, quiet humour and formidable research come together beautifully in his books. While The Emperor Of All Maladies dealt with cancer, Mukherjee’s second book was about genetics and how the study of the gene travelled from monasteries to laboratories. The ‘intimate history’ also delves into Nazi eugenics and similar studies in the mid-20th century that made the study of genes a dangerous and sinister pursuit for some decades, before it once again was reclaimed by researchers in search of clues to diseases, hereditary traits and the like. It is remarkable how those condemned to asylums were routinely sterilised so as to not pass on defective genes to the next generation, even in the US.

What makes The Gene truly special is the parallel narrative of Mukherjee’s personal history and his search for answers in the recurrence of schizophrenia and other mental health challenges. The life of Mukherjee’s uncle drives home the point that all study in the medical field eventually deals with human beings and their intensely personal stories. This strand of the story propels the general narration of the history of genetic studies, resulting in a remarkable, if heavy, tome.

If they have a good book, bibliophiles are known to shut out the world around them.

The Bibliopath is the Queen Mother of this tribe. She writes a monthly

column in t2oS.Talk to her at t2onsunday@abp.in