|

It?s a story about a struggling Kannada author who wins a huge advance and literary limelight by writing a best-selling novel in English. But her sudden celebrity and good fortune trigger a debate over whether she has ?sold out? to the West and abandoned the cause of her mother tongue. If that isn?t enough, there?s also a smaller tale about the protagonist coming to terms with her ambivalent feelings towards her crippled sister. All these unlikely ingredients are woven into an engrossing tale by one of India?s most famous contemporary playwrights, Girish Karnad.

Karnad?s new play, A Heap of Broken Images, represents a departure for the playwright in more ways than one. For a start, it?s the first play he has directed in more than 30 years. Also, it represents a moving away from his much-beloved historical and mythical themes. Karnad?s oeuvre has indeed come full circle: from the mystical Hayavadana to contemporary realities depicted in A Heap of Broken Images.

?One has to make a change sometime, doesn?t one?? asks Karnad. ?The excitement of doing something different ought to be reason enough. One needs change,? he declares. Karnad has kept himself busy over the years writing several extremely popular plays and acting in films. He also served as the director of the Nehru Centre in London.

A Heap of Broken Images and its Kannada version Odakalu Bimba are set in a television studio where the newly-famous author delivers a talk to settle the debate that has arisen over her work and its success. It is more technically involved than any of Karnad?s other works. In a remarkable adaptation of a technique used by many film-makers whereby a character?s conscience talks back at her through a mirror, Broken Images sees the protagonist?s electronic image on the television screen acquire a life of its own, probing, questioning and chastising her till she is forced to acknowledge unpalatable truths about herself.

The media deluge of recent times might have been a factor that prompted him to set his play in contemporary society, says Karnad. Having spent the last three years as director of the Nehru Centre, he was engulfed by a profusion of images, both in the print form as well as the electronic, and this brought home how all-pervasive the media had become in our lives. This is a reality at which he pokes gentle fun in his play, albeit as one of the sidelights.

As for the long-running feud between Indian writers in English and vernacular authors, the so-called bhasha writers, Karnad has seen it develop over the years into a bitter fight. A conversation with author Shashi Deshpande, who recalled a furious debate over the relative merits of the IWE (Indian Writers in English) clan and writers in Indian languages at an authors? conference at Neemrana in 2001, gave him the idea to base a play on this.

Its rather focused theme has not been a deterrent to its success ? an unqualified one in Bangalore where it has run to full houses in both the English and Kannada versions. ?The success of the play is gratifying and heartening, and shows that good theatre will always draw people,? says Karnad. And linguistic chauvinism is not restricted to the literary classes alone. ?Language is something most are passionate ? and possessive about,? he feels.

Personally, Karnad feels the debate is a futile one. ?As A K Ramanujan once said, it is useless to ask whether an author should write in English or not. One should rather ask whether they can.? According to him, there is only good literature and bad literature, and any author who feels happy to write in more than one language should feel welcome to do so. ?As I mention in the play as well, the root of the debate is not about which language you patronise. It is ruled by economics,? says Karnad. The unnamed but purportedly huge advances earned by writers in English, thanks to the larger audiences they reach, are bound to make regional authors envious, and this is ultimately behind the whole squabble, he believes.

Karnad himself is fluent in almost five ?Indian? languages: Konkani, his mother tongue, Kannada and English, in which he writes, the Marathi he picked up in Mumbai, and the Hindi that he speaks fluently. ?Most Indians speak at least three languages, and this is a source of amazement to Westerners, most of whom are monolingual. This obsession with language could well be a colonial hangover,? Karnad believes.

The language debate forms only part of the play?s storyline as it also focuses on three main characters (of course, only one of them is seen on stage) ? the author protagonist, her husband and her physically challenged sister who spent six years of her life with them. The changing relationships between them, universal in flavour, are the mainstay of the story.

The Gnanpith awardee is busy making plans to take his play to other cities, though he concedes that it could be a difficult proposition given the technical details that have to be kept in mind.

The increased interest in theatre in the country, especially the enthusiasm being shown by the corporate world to sponsor plays and theatre festivals, has him feeling heartened and optimistic. The fact that television and cinema, especially the multiplex culture that has the country in its thrall, have not managed to keep people away from his play doesn?t come as a surprise to him. ?Theatre is an extremely engaging medium. The element of risk involved in each performance, plus the fact that no two performances of the same play can ever b e the same, attracts people. There is a certain thrill in watching a play live on stage ? and this is something cinema and television can never recreate. This is what brings people back to theatre,? he claims.

As long as there are people like him around ? those committed to the cause of theatre and in love with the romance of the stage ? the gallery promises never to be empty. The show, emphatically, is bound to go on.

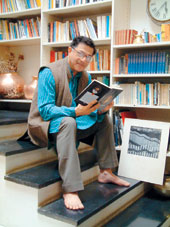

Photograph by Asif Saud