The thought occurred to many on the day of the 2021 Bengal Assembly election results and not for no reason. This year, May 2 also marked the centenary year of Satyajit Ray — director, composer, writer, artist... Bangali intellectual. As the leads trended that day, the thought also occurred that the BJP had shown no interest in Ray. Why so? After all, in the run-up to the Assembly elections, the saffron party had tried to appropriate and reinterpret several Bengali icons: Vivekananda, Vidyasagar, Bankimchandra, Rabindranath, Subhas Chandra Bose. It is curious that despite the fact that this is a milestone year for Ray, there was not a single saffron spin on him or his works. Yes, information and broadcasting minister Prakash Javadekar announced a national level film award after Ray, but that was all.

“I do not think the BJP is ignorant about Ray or that they cannot fathom the depth of Ray. It is just the opposite,” says Sujoy Shome, Ray's associate and former editor of Sandesh, a children’s magazine that was started by Ray’s grandfather Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury and was later run by Ray himself. He continues, “They know exactly how critical Ray was of their ideology and so they have chosen to stay away from giving any saffron twists to Ray.”

He starts to enlist some Ray traits. He was Left leaning. In his three films, Debi, Kapurush O Mahapurush and Ganashatru, he lashed out at the prejudices prevalent in all religions.

“Kanchenjunga critiques purushtantra or patriarchy, Sadgati critiques casteism and oppression of the Dalits. In several of his films, he has expressed high regard for women. The BJP does not afford any respect to women,” says Shome.

Samantak Das, who teaches at Jadavpur University, says, “One reason the BJP did not try claiming Ray as one of their own is possibly Ray’s sense of wry astute, very discerning humour. The BJP cannot stand humour; it only understands mockery.” Das talks about Ray’s commitment to rationality, to secularism, to the liberal ethos, his sympathy for the underdog evident in films such as Aranyer Din Ratri. “And the sympathy can be seen both in the form and the content — in the way he structures his films, the way he looks at the camera. The “subalterns”, the name that is in fashion now for these people, are not someone who are being looked at in his films, instead, it is they who are looking into the camera, it is their perspective, their voice that we hear. They are given their due respect.”

If there is a syllabus of Bengaliness, Ray is an integral part of it. Not because he made “art films”, not because he got the Bharat Ratna, the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, the Academy Honorary Award, the Commander of the Legion of Honour and so on and so forth, but because he created a cultural capital which continues to live and breathe and mean something to a community. Says Das, “He has become a part of the culture. One might be singing Aha ki anondo akashe batashe and yet not know who wrote the lyrics. That is Satyajit Ray. The acceptance of his work has been such that it has become one and same with Bengali culture. His Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne is nothing but a part of our consciousness.”

Ashoke Viswanathan, dean of the Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute, Calcutta, believes that Ray’s genius lies in his genes. Viswanathan has watched Ray closely working in the Shakha Proshakha — his father N. Viswanathan had worked with Ray in Kanchenjunga. “Ray’s father Sukumar Ray was the father of nonsense verse in Bengali literature — Abol Tabol is his brainchild.” However, Ray had lost his father when he was barely three years old. He was deeply influenced by his mother and his grandfather and later by his aunt Leela Majumdar.

A theory goes that Ray had possibly started making movies for children with Hirak Rajar Deshe. His son Sandip, who was a child then, had asked him to make a movie for children and so he did it. “But Hirak Rajar Deshe is not a children’s movie per se. It is an adult’s narrative for children,” says Siddhartha Chatterjee, one whom we see as Topshe in Sonar Kella. (Actually, Ray's screen venturing for children began with the making of Goopy Gayen Bagha Bayen, a work ahead of Hirak Rajar Deshe.)

Topshe shares his experience of working with Ray. “I was merely 13 years and a few more months old when I did Sonar Kella. I was too young to understand who Satyajit Ray was. We were two children on the set — Mukul and me. Ray never came across to us as a director. He loved children and had studied them very closely, their psychology and what triggered them.”

Ray’s work was manifold but broadly it had two aspects: his films and his contributions to Sandesh. But very often, the two mingled and merged — the music and the scripts, the detective stories and the science fiction writing, all of what became embossed with Ray’s eye and art. He would, of course, illustrate his own work.

Goutam Ghose, who made a documentary on Ray, has seen his laal kheror khata wherein Ray would lay the blueprint for his films. “Ray was extremely organised. He used to plan everything, from scripting, to dialogue to costume, set, scene. His kheror khata, which starts with Aparajito, has illustrations, musical notes, drawings,” Ghose says and adds, “Ray had not seen a computer, he had not seen a workstation, mobile phones were not there; there was no Internet. His kheror khata was his own created workstation. He used a kheror khata because his father would use it. He would often say, ‘I know my father from his writings. He is my inspiration’.”

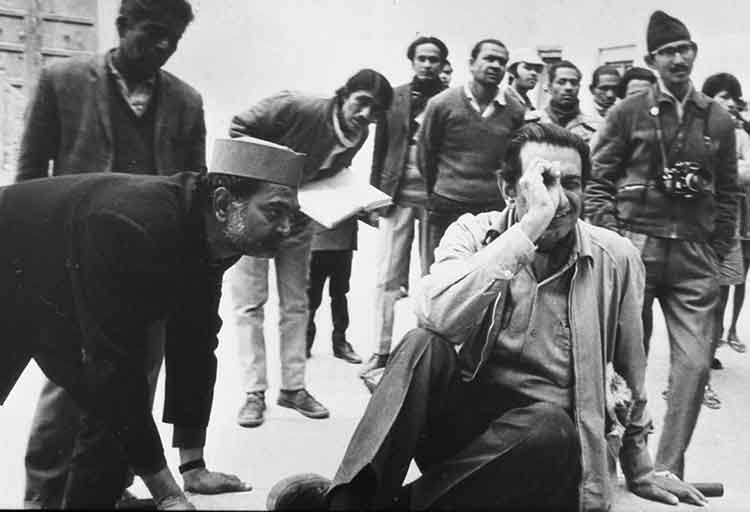

Satyajit Ray at the shoot of Sonar Kella in Rajasthan. Sourced by The Telegraph

Precision also marked his music composition. “That is because Ray had grown up listening to a lot of Western classical music,” says music composer Debajyoti Mishra. “Later in Santiniketan he got to listen to other kinds of music — from Rabindrasangeet to folk songs, everything. Ray’s music, I would say, is an assimilation of all these things and yet again it was completely original.”

Ray used to compose songs in Western notes first and then replace them with Indian notes for Indian musicians. There was a shade of Mozart in his music. For example, his Feluda series. Mozart’s Symphony No. 25, its notes, its flow, brightness, childlike quality mingles appropriately with the theme of adventure and thrill in Feluda. Even so, the composition is uniquely Ray’s.

Ray lived through a time when Bengal was wracked by political turmoil, from the pain and suffering of the Partition of Bengal to the strife of the Naxal movement. He was an engaged and conscious artist, he responded with his art. Films like Agantuk, Shakha Proshakha, Ganashatru speak for themselves. Agantuk shows how a country can be destroyed at the wag of a finger, Shakha Proshakha shows the complete breakdown of all value systems and Ganashatru critiques religious prejudices and how scientific reasoning is affected.

But Ray’s genius resided not in him alone. He was a team player. “Unlike many others, the greatness of Ray was not limited to his talents and skills,” says Viswanathan. “It was his entrepreneurial skill that took him to heights, more than anything else.”

Did we learn much from Ray? “I doubt it,” says Madhabi Mukherjee, one of his fabled heroines. “Today, I am getting so many calls asking about Manikda. But nobody recognised his talent during his lifetime.”

She adds, “Ray represented reality in a way that it would remain close to reality. If he was showcasing a scenario, say rural India, or he was depicting the poor, one would discern it in his use of costume, in his use of props, in his choice of setting. He portrayed life as it was, just as it was. Satyajit babur cinema-e kono kichhui asundar chilo na, kono kichhui kuruchikar chilo na... In Satyajit Ray’s films, there was nothing that was ugly or in bad taste. Pather Panchali is not removed from reality but it is still beautifully done. He taught us to capture beauty in everything — dialogue and script. How come people are using filthy language in films? Why is it that the representation of reality goes missing in the films? Have we forgotten what Ray and his contemporaries taught us — Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen, Saroj De, Bibhuti Laha?”

Do look around. Or ask yourselves why. Ask the question that occurred to many as the Bengal results rolled in on his hundredth birthday. In doing so, you may have paid some tribute to Ray.