Even if you have not noticed the briefs running down the sides of newspapers — with headers such as “15 Arrested For New Town Call Centre Fraud” or “Seven Arrested For Salt Lake Call Centre Fraud” — you would have heard it from the grapevine.

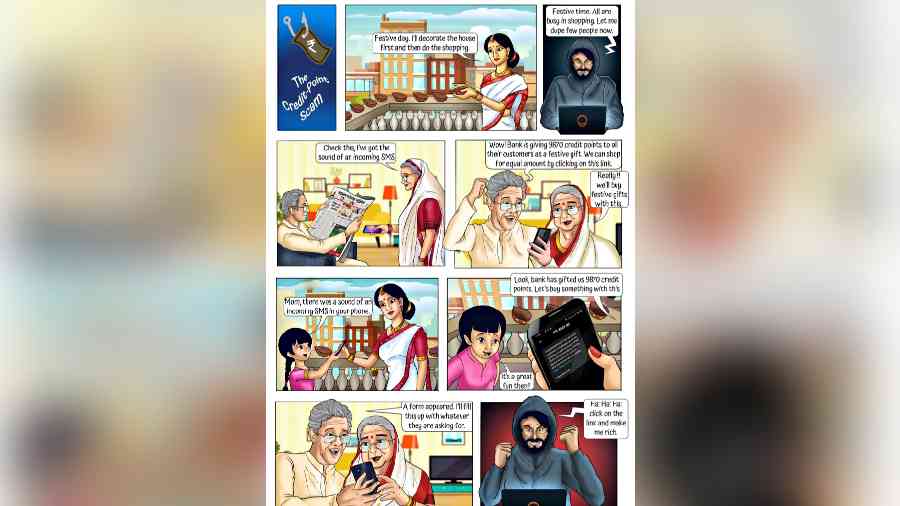

Someone received a text message alert about electricity dues, and an ultimatum to pay up using some app or risk a snapped connection. A harried visit to the electricity office revealed that the message was fake. Someone got a WhatsApp message from an international number threatening to make public personal videos. Eventually, cops said it was a virtual trap. Someone else lost Rs 65,000 when a scammer pretending to be a bank employee called to update KYC details.

You are certain to have received calls and texts in the name of insurance companies or the corporation office. You might have watched the new season of the Jamtara web series too. You may have been lucky so far, but with the exponential increase in the number of scammers, chances are you will trip up soon.

“Jamtara is no longer the centre of cybercrime,” says special public prosecutor and cybercrime lawyer Bivas Chatterjee.

He adds, “It is right here in Bengal. The entire area from Salt Lake Sector V to New Town is where the online frauds are happening.”

These call centres operate out of apartments or houses. They are fitted out with a dozen computers, a private server to receive and make calls (without using any SIM; that should explain the unsolicited calls from numbers with strange ISD codes), store and send data (including OTPs). Sources in the cyber cell department of Calcutta police claim there are nearly 1,600 non-verified fake call centres in the city’s IT hub, employing an estimated 10,000 men and 5,000 women.

And who is the scammer?

Regular people, men and women in their 20s and 30s, most of them picked up by employment agencies who advertise for “call centre executives” in print media and also on local cable TV. Walk-in interviews happen across the small towns of Bengal and also neighbouring Jharkhand and Bihar. Says a CBI source, “There are hardly any jobs available in these areas.”

Those hired get trained. Soumendra Padhi, who is the director of Jamtara, shares some of what he knows from his Jamtara recce. These young people are mostly college dropouts. They go through the routine “voice training”, which includes the basics of communicating over phone. The job itself, in call centre parlance, is known as “calling”.

One person makes as many as 100 calls in a day; of these even if two are successful it would be a good work day. Once they have worked for a bit, some of them go in for next-level training.

They learn to speak in Malayali and Marathi. Why? Apparently, a large percentage of NRIs belongs to Maharashtra and Kerala. Teachers charge Rs 1,50,000 per student per month. The tuition fee comes out of their savings.

Beyond all training there is potential. Chatterjee provides a psychological profile of the scammer. Introvert, impatient, casual, prone to anger, tech-savvy, ambitious and looking to earn big sums of money in no time.

A scammer does a lot of research before selecting a target — age of the victim, bank balance, location, employment history. Data is usually purchased online from companies for a fee. According to sources in the police, bank employees often help them locate accounts of senior citizens with a steady balance of over Rs 50,000.

SIM cards are kept ready. A scammer with whom The Telegraph spoke says, “I got one in the name of a person who is long dead. You cannot trace it back to me.” His voice is playful, casual, carefree. “Nobody comes to verify your address after you buy a SIM.”

At other times scammers provide valid ID proofs. Did you know that when you go to the neighbourhood photocopy shop for a print of an Aadhaar or a PAN card or a voter ID, they may be keeping an extra copy for themselves to sell to call centres at a price?

The SIMs go into stolen handsets. “Once they are successful in duping someone, they destroy the SIM. They do not always dump the phones as they are stolen property and will be traced back to the original owner,” says a source in the cyber cell department. But once a SIM has been successfully used for an online fraud, the scammer destroys it immediately.

According to Chatterjee, the scammers are clever in picking their victims. They go for the elderly, and even among them, mostly those who live alone. The moment you submit a spouse’s death certificate to your bank, the scammers are alerted. They also target people in other countries; even that data is available.

Traps for domestic victims vary. Claim your lottery win after paying a levy by clicking on a link. Discounts on hotel bookings by becoming a member of some famed hospitality company. Easy loans in exchange for a token EMI, and so on and so forth.

A fresher makes Rs 10,000 to Rs 12,000 per month. The lion’s share goes to the owners of the fake call centres who hire these scammers. No one is willing to go on record but these call centre owners are not entirely unknown to the keepers and makers of law or their largesse.

Freshers are mostly unaware of the criminal nature of their work. By the time they understand the business model, either it is too late to escape, or it is too exciting to give up, says Chatterjee. There are many executives who learn the model and even start their own businesses.

Chatterjee says, “India has been listed as a scammer country. Foreigners too come here in search of cybercrime opportunities.” These people come as tourists, students or sportspersons and stay back even after their visas have expired. Chatterjee adds, “No one monitors these people. They move to the northeastern states, marry local women, create a new identity for themselves, open bank accounts in the name of the spouse and safely transfer money through those accounts.” They also use dormant accounts to transfer money to Dubai and the Middle East, which is why it is best to close dormant accounts.

The Jamtara model — making calls in the guise of customer care executives — is apparently very last season. As the general public has turned more cautious, scammers have had to think up new ways of scamming. Nowadays, it is more common to send a link through which an eSIM can be generated. This makes it possible to control a device. “With 5G, this is becoming a norm. Scammers can control your device and get access to the OTPs,” says Chatterjee. So if a caller calls and asks if they can update your SIM to 5G, disconnect immediately and turn off your mobile data.

Chatterjee says, “The message has gone out to scammers that neither the administration nor the judiciary can stop them.”

And that’s where we are, for now.