|

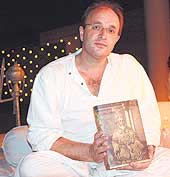

He is more a Dilliwala than a Scot and is unarguably the darling of the Capital’s literati. So when he launched his latest historical saga, The Last Mughal The Fall of a Dynasty Delhi 1857, his Delhi buddies came out in full force to get their copies of the book autographed. William (make that Willy) Dalrymple, reclined regally on a divan as he read out excerpts from his latest magnum opus. Late arrival, political honcho Mani Shanker Aiyer was happy to stand throughout the proceedings while former Himachal Pradesh chief justice, Leela Seth (and mother of writer, Vikram Seth), queued up later for a quick congratulatory hug.

Dalrymple whose humorous take on Delhi, City of Djinns continues to be a bestseller even 15 years after it was published, has reasons to be pleased. “This is my second fatty in five years,” he says tapping a copy of The Last Mughal (Penguin). And he’s glad that this 600-pager is making readers sit up and take note, just as much as his last fatty, White Mughals did.

The Last Mughal is a racy account of the dying days of the Mughal reign, with Bahadur Shah Zafar as a central figure and the 1857 Mutiny as the backdrop. With India marking 150 years of the Mutiny next year, Dalrymple is hopeful the book will provide food for thought in universities just as much as in drawing rooms.

He is clearly hooked on the Mughals. For, even before he can take a breather after his latest narrative, he has more in the pipeline. He has signed a contract with Bloomsbury, the UK-based publishing house to pen three prequels to The Last Mughal — beginning at the very beginning with the first Mughal emperor, Babur. “That should take care of the next 20 years,” he says.

When you pick up The Last Mughal be prepared for some surprises. While the focus of most Indian research on the Mutiny focuses on people like Mangal Pandey and Rani Jhansi, according to Dalrymple they were in fact small players in the events of that era. “Mangal Pandey was a great patriot but his March outbreak did not directly result in the uprising in May.” So too Rani Jhansi, though several books have been dedicated to her. Dalrymple’s research also indicated that the uprising was, above all, a war of religion as what the rebels or sepoys most objected to in the foreign domination of their country was the way the British threatened their religions.

The genesis of the book can be traced back to the time when Dalrymple chanced upon some 20,000 hitherto unexplored Mutiny papers written by Indians. Most of these were written by the rebels in Urdu and Persian in the sepoy camps or the Red Fort and they all found their way to the National Archives in Delhi. “It’s the most spectacular historical record that exists,” he says. Only a small number of these documents have been referred to by other scholars and of the material that Dalrymple studied, 85 per cent hadn’t been touched by anyone else.

What has surprised Dalrymple is that no Indian historian has hit upon these records before him. “Perhaps it’s because most people writing history in India are English speaking and have little knowledge of Persian or Urdu,” he says. Translating languages could have become a stumbling block for him as well if it hadn’t been for his colleague Mahmoud Farooqi. “He’s fluent in both English and Urdu. This book is as much mine as his,” he says. For the Persian translations he banked on Bruce Wannell who’d helped him during the writing of White Mughals. Usually the three of them would pour over manuscripts, magnifying lens in hand.

Their research took about four years. Largely, he split his time between Delhi, Rangoon, Lahore and the National Army Museum. Dalrymple spent hours typing notes on his laptop in the National Archives in Delhi. He says, “Two-thirds of the work was done here.” In Lahore he found material for the period before the outbreak, while in Rangoon he stumbled upon the complete prison records of Bahadur Shah Zafar.

And then he wrote quickly between February and August this year and finished writing the book in five months flat. “But hideous panic set in as the deadline approached as I had to further sift through enormous material,” he says.

But at any point during his research, did he ever get bored? He says emphatically, “There was never a dull moment. History can be depressing when you have to try and find a new angle to what has been written hundreds of times before. But at no stage did we feel that we were working through old material.”

His attempt as a historian has been to make history accessible to everyone — in each one of the five books of history and travel that he has written. He calls his kind of writing narrative history and says that he’d like to humbly put himself in the same league as Simon Schama, professor of history in Cambridge (where Dalrymple himself studied) who writes very well researched history books. “Jargon excludes and obscures rather than illuminates,” he says firmly.

Now that The Last Mughal is out of his system, he has many plans up his sleeve. Besides hectic countrywide promos for the book, he intends to take a break, travel a lot and maybe even lie back in a planter’s chair reviewing other people’s books. But he’ll be out with a collection of essays on Hinduism, Islam and Christianity sometime next year.

With a little more time on his hands he intends to deepen his affair with the country, for one. He’s loved India from the first time he landed in Delhi as an 18-year old in 1984 as a backpacking tourist. He took a job at Mother Teresa’s home and in his spare time explored the interiors of Old Delhi. Over the next 20 years, he has divided his time between London, Scotland and Delhi.

Now he’s very comfortable calling Delhi home and lives in a farmhouse in Mehrauli. He lives here “with lots of peacocks”, his artist wife and three children. However, he is sure that over time his obsession for Delhi will only deepen. “The only time I am not passionate about the city is during May. That’s when I ask myself why I didn’t choose to write about Bali,” he laughs. “But I will never be bored of her (Delhi, that is),” is his promise.

Photograph by Jagan Negi