If you step into the narrow lane beside the chop shop on the winding Shyama Charan Dey Street off College Street, you will notice a narrow entrance with blinding white walls. From this point, you will be able to see the bookshop.

Ceiling-high bookshelves stacked with beautifully packaged tomes that invite you to browse. Plenty of stools scattered all over the place so you can sit and read. No one interrogates you or hassles you or in any way hurries you to just choose a book and leave. In other words, it is a book lover’s paradise.

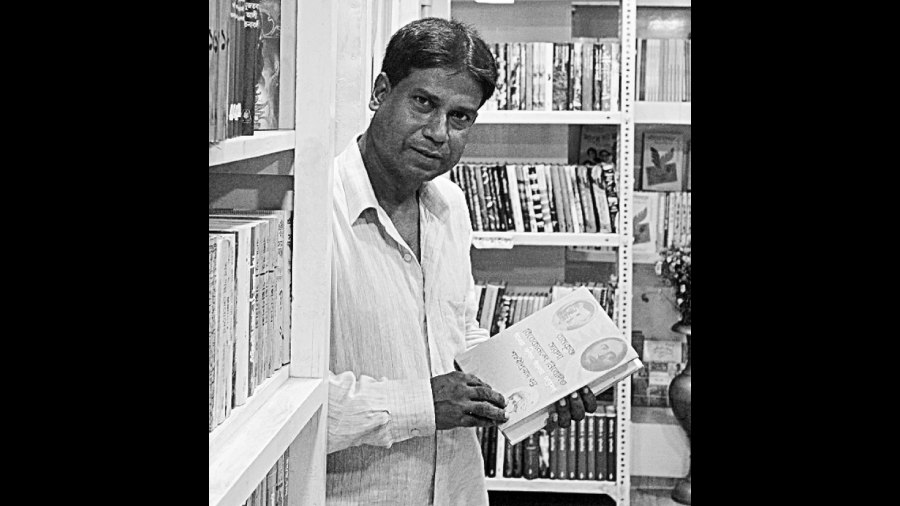

It is also the dream — and a labour of love — of the middle-aged Nemai Gorai, an ardent reader who at one time lacked the funds to indulge himself. He wanted to create a haven for book lovers like him with limited means.

Gorai arrived in Calcutta in 1992 from Kutulpur village in Bankura district. He took admission in City College but, within three months, the assured funds from home dried up. Unable to pay the fees, he quit college but not the city. He started tutoring children, found cheaper lodgings — sometimes that meant under the open sky — and managed, though barely.

Eventually, he scraped together a bit of money and invested in a business. His place of work was a 3x1-foot niche at the busy 2B bus stand in Bagbazar in north Calcutta. He sold newspapers, magazines and cheap ballpoint pens from there. During this time, perhaps inspired by the publisher’s line on the goods he sold, he decided that he wanted to publish a book.

Unfortunately, while he had the funds, he did not have the permanent address required for a publisher. An elderly gentleman, who lived next to the bus stand and had become quite friendly with the hard-working young man, came to his rescue. He allowed Ghorai to borrow the address of his ancestral home.

Gorai used his contacts to get in touch with famous Bengali authors such as Sunil Gangopadhyay and Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay. He persuaded them to give him the rights, for a sum of Rs 500, to the favourite ghost stories they had written. He then put together these stories in Saada Bhoot, Kalo Bhoot (White Ghost, Black Ghost), loaded the few hundred copies he could afford to print on a cycle van and peddled them on busy streets.

The other type of books his customers demanded were cookbooks. So sometime in the early part of this century, Ghorai approached a man called Vincent Gomez to collate a cookbook for him. Chef Gomez was the son of Nehru’s official chef Sir Gomez and was part of the prime minister’s kitchen, says Gorai. The publisher designed a smart-looking book, which sold like hot cakes, bringing in quite a bit of money for Gorai’s Surya Publishers.

But Gorai had even bigger dreams, he wanted to print coffeetable quality books with archival value. And that is why, 13 years after he started Surya Publishers, he decided to approach the son of the late Bengali writer Lila Mazumdar for the rights to bring out a comprehensive collection of her works.

There was much demand for Mazumdar’s work, so many well-known publishing houses were keen to acquire the rights to them but her son Ranjan Mazumdar refused to entertain publishers. So Gorai did the next best thing — he sought an appointment with dentist Ranjan Mazumdar as a patient.

Since there was nothing wrong with his teeth, he decided to get them scaled. And then, he let it slip that he was in the publishing industry. It took him three scaling sessions — one every three months — to gather the courage to tell Dr Mazumdar the real reason for seeking him out. That done, a few more months passed before the man agreed to look favourably on his request, and still more time passed before they signed an iron-clad, 15-page contract to seal the deal — possibly the longest contract ever signed in Calcutta’s publishing circles. And yes, Dr Mazumdar reserved the right to cancel the contract if the production wasn’t up to the mark.

Over the last 13 years, Gorai’s Lalmati Publishing has brought out 13 volumes of the collected works of Lila Mazumdar. Lalmati’s logo is a stylised terracotta horse — a nod to his home district Bankura with which this horse is synonymous.

Emboldened by his success with Dr Mazumdar, Gorai decided to approach Narayan Debnath, author of the popular Bengali comic strips Bantul the Great, Handa Bhonda and Nonte Fonte. His cartoon strips were tied up with different publishing houses that treated them as no more and no less than comics. But Gorai wanted to publish archival material. And he approached Debnath for the right to publish his collection. Debnath agreed and Gorai then decided to move forward with publishing more collections of cartoons, including an English translation of Bantul the Great.

Bengali books, most often than not, are likely to be perfunctorily designed — it may have something to do with the Bengali reverse snobbery on looks — and cheaply printed. Gorai wants to change that. The books Gorai publishes are all well-designed — often by the man himself — and printed on quality paper in easy-to-read fonts. He says that is the only way to attract new readers, to encourage a love of books.

The bookshop Borno Boimahal is the next step. It will be some time before we know if it will take the love of books as far as the love of books has brought Gorai.