|

I’m a walking talking contradiction,

Living in a world of fiction (Walking Talking Contradiction, Public Issue, October 2005)

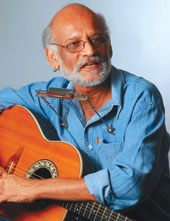

When Sushmit Bose sang these words at a concert on October 7, launching his latest album, Public Issue, he could have well been singing about himself. For he’s a bit of a square peg in a round hole, singing about serious social issues in English to Indian audiences. But if there’s one place where Sushmit Bose fits in perfectly, it’s onstage, under the arc lights ? singing what he calls ‘urban folk music’, about social issues and changing trends in Indian cities.

“The one overriding conviction that has settled into my guitar-playing fingers is that culture is the best way of sending a message about the most complex issues,” says he, giving the example of how Martin Luther King mobilised all of America with the anthem We Shall Overcome. In the 60’s and 70’s, an entire generation of Americans rocked to the hard-hitting music of singers like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, who sang about the politics of the cold war, Vietnam and the angst of urbanisation. As a student, Bose realised that it was only a matter of time before Indians addressed similar social problems and issues that seem to go hand in hand with ‘development’.

“I grew up listening to this sort of music and wanting to be a singer myself. But I wasn’t prepared to sing in smoky nightclubs wearing a suit and a bow-tie,” reminisces Bose, “so I became a singer in modern India inspired by my icons of social change in the West. I began to sing about peace, the ravages of strife and war, and the demented chasing after the good life.” And that is why he chose to sing in English on themes like AIDS, child abuse, child labour, human rights and more, which relate to a rapidly urbanising India in ways that traditionally rural folk music can’t. “I believe,” says he, defending his decision to sing in English, “that social change in our country can only be brought about by its English-speaking middle class. And that’s the audience I’m targeting!” Also, he points out, that this has ensured that his music can be heard across the country from the South to West and the North East.

His first album, Winter Baby, brought out by HMV (EMI) in 1973 was on child abuse, a subject few spoke about, let alone sang about. “People told me it would never work, the subject was too heavy and nobody would listen to it, but I went ahead anyway,” he says. His next two albums, Train to Calcutta (1978) and Man of Conscience (1990), released by CBS to coincide with the visit of Nelson Mandela, also received a good amount of critical acclaim and exposure among social organisations. He also released a music video, Do You Hear The Children? from Man of Conscience. Ever since, he’s performed in gigs in India and abroad, concentrating on music as an advocacy tool. “Over the years, I’ve affiliated myself to civil society organisations like Sahmat, UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) and HAQ (Centre for Child Rights) ? who’ve understood the value of mixing art with advocacy and used it to good effect,” says he.

Over the years, Bose has tried his hand at all sorts of creative projects. A talented filmmaker, he’s produced several successful television shows for Doordarshan, Surabhi, a show on Indian culture being amongst the best-known. He has also released documentary films like Akha Teej ? on child marriage; A Revival ? on traditional medicine, For Who; Man Of Heart ? on the bauls, for IGNCA (Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts). He also arranged the song Hum Honge Kamyab with Anil Biswas and has led the All India Radio Choir. He’s performed in international folk music concerts from Cuba to Berlin, and has sung with folk music legends like Pete Seeger in the US and Canada. He has also performed with Paul Horn, an internationally acclaimed flautist, for a US/UK project on world music.

What also sets him apart from other Indian singers is that he pens his own lyrics. Public Issue, his fourth album brought out with HAQ and Viveka Foundation, was released in early October, and contains 14 brand-new songs in the best Dylanesque tradition of social cause poetry. Some songs on the new album are poetic, others evocative, made more so by his slightly raspy voice and the trademark harmonica. Often, his songs are hard-hitting: singing about the plight of child weavers in the Indian carpet belt, he sings, “Who do they question, who will they seek,

Their fathers or their mothers or the man on the street

Or the one who stands besides them, should he be blamed

And the finger points at you and me.”

(Who’s to be blamed, Public Issue, October 2005)

The most interesting song on the album, Nirakaar Noire Bhojon, is sung in the baul tradition, and is about the futility of mosques, temples and churches to seek God. “I couldn’t play any of the traditional instruments which accompany baul songs, but the American banjo filled the void beautifully,” said he.

How do you speak of freedom?

When your thoughts are so in chains

How do you see the rainbow?

Without the rain

(Certain Thoughts, Public Issue, 2005)

The songs in Public Issue have been welcomed by civil society organisations who want to include music as part of their advocacy campaigns. A long term ‘Art As Advocacy’ programme with Viveka Foundation and HAQ (the two sponsors of Public Issue) is on the cards.

“People often call and ask me for copies of my lyrics,” he says, “And when I see the kind of response that my music evokes in young audiences, I feel even more certain of the efficacy of music as a tool for public advocacy.” Perhaps that is why unlike many other musicians who’ve sung one or two songs with a social theme, Bose’s music has consistently been about social justice. “In the last 30 years, I haven’t sold my soul to music without meaning. I have sung what I believed in, and believed in what I’ve sung,” says he. Dylan would have been happy.