|

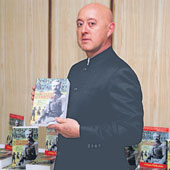

How did a one-time soldier of the British Army, leading men as varied as the Gurkhas and the Baluchis, come to write a book on one of the most hated names in Indian history, General Reginald Dyer? The story behind how author Nigel Collett?s book The Butcher of Amritsar got written is as fascinating as the book itself.

By his own admission, Collett had never been your regular Indophile or exactly interested in Indian history. This 52-year-old British-born author, now living in Hong Kong, read history at Oxford and then took up a military career after passing out from the elite Sandhurst Institute. Then, in 1981, he was seconded to the Sultan of Oman?s Land Forces. All the soldiers he led were from Pakistan and Baluchistan and he got interested in the customs and culture of the Baluchis. Among the books he read then was one written by General Dyer ? an account of his time in Baluchistan and the fights between the British and the warring tribes. ?It was an enjoyable book, a kind of boys? adventure story. Dyer wrote about how the tribes were overcome by trickery and stealth and not by main force,? recalls Collett, a true-blue ?propah? gentleman, though minus the famous stiff upper lip.

When he read the book, Collett?s knowledge of General Dyer and the part he?d played in Indian history was scanty. Some four or five years later, he watched Richard Attenborough?s film Gandhi and realised what a different man Dyer must have been. This paradox between the adventure-loving, almost boyish soldier and the man who murdered in cold blood hundreds of innocent people held a fascination for Collett. After leaving the army, he became an academic again when he did a master?s degree in biography in England. He chose Dyer as his dissertation subject and this eventually became the basis for the book.

?I found remarkable similarities between Dyer?s life and my own,? recalls the author. ?I was born in a village near Swindon that was very close to the Dyers? old home. Like him, I went to Sandhurst and served in the Army, mostly leading foreign troops. And incidentally, most of the races we led are also in common ? like the Gurkhas and the Baluchis.? But the similarities end there, he stresses with a smile, for Collett is passionate about human rights and opposes prejudice of any sort.

In fact, he mentions how his friendship with four Gurkha officers he met in a British training team while posted to the Zimbabwean Army in Harare made him apply for a transfer to the Brigade of Gurkhas in the British Army. Not only does he speak, read and write Nepali and Baluchi, he?s also written several grammar and vocabulary books on the two languages. ?Obscure languages are something of a passion with me,? says Collett.

The Butcher of Amritsar draws a detailed, minute and not too pretty picture of General Reginald ?Rex? Dyer. It traces Dyer?s life from before his birth ? the family had been settled in India for two generations ? and examines the various people and incidents that made Dyer the man he was.

Early on in the writing of the book, Collett decided that the angle he would take to decipher Dyer?s motivations for what he did would be social and psychological. ?It was the seemingly irreconcilable difference between the man I had in mind when I read that book written by him and the man who was the perpetrator of the Jallianwala crime that convinced me the answer must lie in his psychology,? says Collett.

What Collett is clear about, though, is that in delving into Dyer?s psyche and exploring the fear and paranoia that led him towards Jallianwala, he isn?t finding excuses for Dyer. In fact, the very title he chose for the book reveals his attitude. ?It?s very difficult not to take sides in something like this,? says Collett, ?for Dyer was not acting under any instructions. Neither was he a sick man. He chose to do what he did because he?d grown up in the shadow of the Mutiny and failed to recognise that this political struggle for freedom was very different in nature.?

Dry as the subject might seem, he has tried to keep the tone of the book readable and conversational. ?As a soldier, I had to write a lot of military manuals, and I didn?t want this to turn into one,? laughs the author. He also feels the book has special significance in the parallels that can be drawn between the colonised world of that time and what?s happening today in Iraq, Afghanistan and even post 7/7 Britain ? the conflict between races and heat of the moment acts to curb the violence that arises from this conflict. ?I never looked at it that way while I was writing the book, because the situation was different when I started researching it. But, yes, I do see the parallels now. There are a lot of lessons to be learnt from history, but the fact is, hardly anyone learns it, least of all those in positions of power,? he says ruefully.

While he travelled extensively in India to research the book, and fondly remembers a Mrs Bhandari at whose guest-house he stayed in Amritsar, his latest tour of India has of necessity been short. The book was launched at the grand old Raj Bhavan in Bangalore, and Collett wishes he had more time to see the city. The one place he has to visit, though, is an old second-hand book-shop in Bangalore?s Church Street that someone recommended to him. Maybe he expects to find a rare old copy of one of E M Forster?s books ? his favourite author and possibly the subject of his next biographical venture. ?I want to write about the time Forster spent in India and the close friendships he forged here,? is all he will say now.

In the meantime, he has to return to Hong Kong where he runs a human resource consultancy with a partner. An unusual occupation for an author, it may seem, but then they do say everyone has a book or two in them. Clearly, Collett?s love affair with India is far from over.

Photograph by Jagan Negi