|

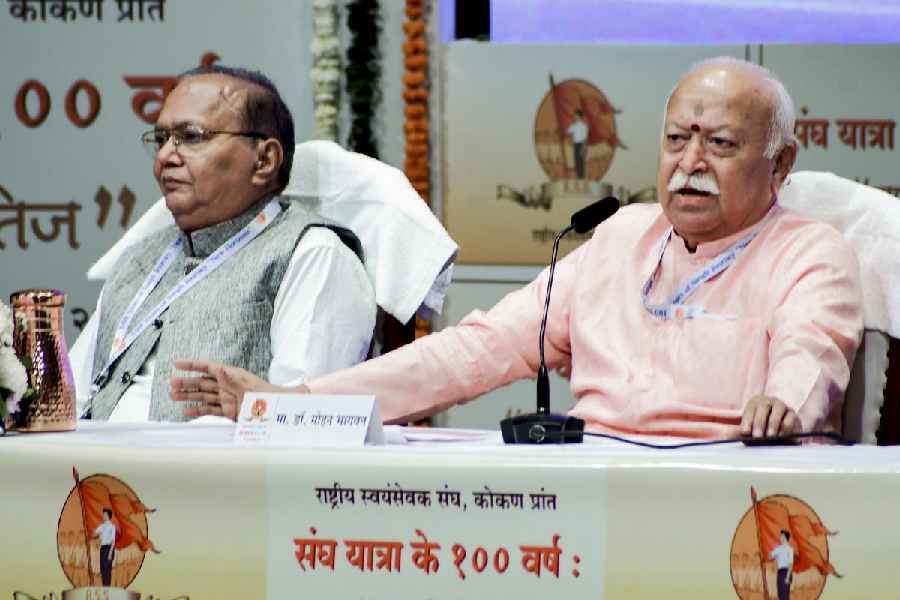

| Sreeranjini GS of Kavade Toy Hive holds workshops in schools explaining the significance of the ancient games;PixbyJagadeesh NV |

|

They might seem like poor cousins to Nintendo, the iPod and the other accoutrements of a modern childhood. But there are still plenty of people around who remember long lazy summer afternoons spent during childhood playing Gilli-Danda with their cousins or battling over a game-board like Chaupad.

Now a handful of entrepreneurs who aren’t afraid to go against the tide, are trying to bring back Indian origin games — and as a bonus most of them are made from eco-friendly mater- ials. So, try your hand at Chaukabara, a strategy game, or even the hunting game Adu Huli Atta which is played by two people — one controls three tigers while the other controls a flock of 15 goats. Or settle for a quick game of Pagade, which you probably better know as Ludo.

Take a look at Vinita Siddharth who runs the Chennai-based Kreeda, which makes traditional Indian toys. She says: “I wanted to capture the spirit inherent in some of our old Indian games. As a kid I loved playing with my spinning tops and even tamarind seeds and shells.” The idea of launching the company germinated one day when she saw her son playing a game of Pallanguzhi with her grandmother. Pall-anguzhi is a board game that originated in south India.

Or, look at Mumbai-based game enthusiasts Manisha and Vaishali Gadekar, who launched KEC Games in 2009 to revive some of the dying crafts of India and also giving children different options to choose from. Today they offer a smorgasbord of about 40 games including Bagh Chal (Tiger Moves) and Pacheta which is a traditional Indian five-stone game, the sort that used to be played in the villages under a tree.

|

| KEC Games is trying to revive forgotten favourites like Lagori, a game traditionally played with stones stacked upon one another |

KEC is also attempting to revive forgotten favourites like Lagori (traditionally played with stones stacked upon one another). Their games are all priced between Rs 100 and Rs 700. Recently, they have introduced a game of Saap-Seedi (Indian snakes and ladders) printed on a cloth which can be rolled up when not in use. “This has been designed by Gond craftsmen and the ink is made from soy-oil,” says Manisha.

One of the strongest plus points of these Indian origin games is that they are environment friendly. There is not a trace of plastic in any of them and they are made from natural materials like wood, cloth and palm leaf.

Kavade Toy Hive in Bangalore owned by Sreeranjini GS also has an array of games made from natural materials like palm leaves, wood, fabric and even elephant dung. “The objective is to make children aware of environmental issues. Also, children today are dependent on computerised games and television as their main source of entertainment. These simple games can be alternate means of fun,” says Sreeranjini, who offers a wide array of traditional games like Vimanam (this is a race between two players played with cowrie shells) which is played on a Kalamkari printed canvas.

|

| (Top) Bangalore’s Red Bug Kreative Kits offers do-it-yourself kits that allow kids to make their own fun toys and functional items from scratch; (right) the hotsellers from Kreeda’s collection of traditional games include Chaupad, Pallanguzhi and Vanavas |

|

Similarly, Siddharth makes the game Pallanguzhi (a cup and coin game) from fibre instead of wood to help “forest conservation”. Kreeda’s games are printed on canvas or cloth and rolled-up in little cardboard boxes made out of recycled paper. These are priced between Rs 100 and Rs 700 and are available in lifestyle stores across India.

Kavade Toy Hive also offers other exotic games like Chaukabara (a strategy game played on a mat with zari work and played with cowrie shells). There are also colourful lacquer- finished spinning tops with non-rust nails that are safer for children to play with. “These are also beautiful as collectors’ items,” says Sreeranjini, who holds workshops in schools explaining the significance of the ancient games. Her are priced from Rs 20 to Rs 400.

The other benefit of these games is that they give a boost to craftsmen all over the country. There are, for instance, the wooden toy craftsmen of Channapatna in Karnataka and makers of stuffed toys from the Kodaikanal area. And, of course, there are wooden folk toys from north India.

Take a look at sisters Anu Parthasarathy and Rupa Vijendran’s craft-kits brand Red Bug Kreative Kits in Bangalore. “One of our primary goals is to help artisan communities continue with their work,” says Parthasarathy. The duo works with artisans from Channapatna, terracotta craftsmen from Bengal and Orissa and Sanjhi (paper-cutting) workers from Uttar Pradesh. They are also involved with block-printers from Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh. Their products include do-it-yourself kits for fun toys and functional items for kids like pencil boxes, bookmarks, fridge magnets, pencil caps and utility boxes and holders to store items. Says Parthasarathy: “The kits come in handmade boxes with necessary parts and instruction manuals with assembly instructions.”

Reinventing these old games proved to be a challenge for many of these entrepreneurs. Says Siddharth: “Since these were all ancient games we had to rely on the memories of old people who’d played them during their childhood.” Siddharth and her team made several trips to old-age homes and villages to unearth some of the regional games and the rules of playing them.

And as Sreeranjini puts it, “There’s no generational limit to play these games. Besides being a source of fun, these games help in bonding and interacting within families.”