When I meet him, Mana Dey is standing right in front of his small office in central Calcutta’s College Street area — a man of average build dressed in pyjama-kurta; his white hair brushed back and tied in a ponytail. The tiny room has a big table in the middle, papers stacked here and there, books and a small computer. The 77-year-old runs his printing business from this place.

Dey was born and brought up on College Street. His father owned a sweetshop on College Row — Santosh Sweet Shop. He says, “I have seen College Street grow over the years.”

The printing business is his own; he started it in 1963. Since then, Dey has been printing magazines. “Chaturanga, Utsa Manush, Anushtup, Ekkhon, Paschim Banga Loko Sanskriti Patrika, Anwesha, Kalyan Barta Patrika...” he rattles off the names. Dey has seen College Street evolve into boi para, a demesne of books.

He shuts his eyes and starts to map out the College Street he knew as a child in the 1950s. “College Row did not have a single bookshop. Shyama Charan Dey Street had only two. There were a few libraries on the street where Dilkhusha Cabin stands now,” he recalls.

It seems the area was dotted with libraries — Mitra and Ghosh Library, Mahes Library, Prakash Bhavan... Dey says, “Near our sweetshop, there was Popular Library. It would open twice a month. An astrologer would come here to do business.”

In the late 1950s, four or five publishing houses came up on College Row. Dey’s, Mondal Brothers, Mondal Sons, Katha O Kahini, Rabindra Library and others came up with their shops on Shyama Charan Dey Street. And then came the Naxal movement.

Suddenly chaos took over this area,” says Dey. “Those days I was into theatre. College Street was the seat of culture. There were theatre groups in and around the place. I started getting involved with them.” He continues, “One night I was returning from a rehearsal, when I found myself caught in a crossfire. But when they spotted me, they stopped and let me pass. What I mean is, those days there was an ideology. The Naxalites were at war with the government and its police machinery. I was not their target and they were not out to kill innocent people.”

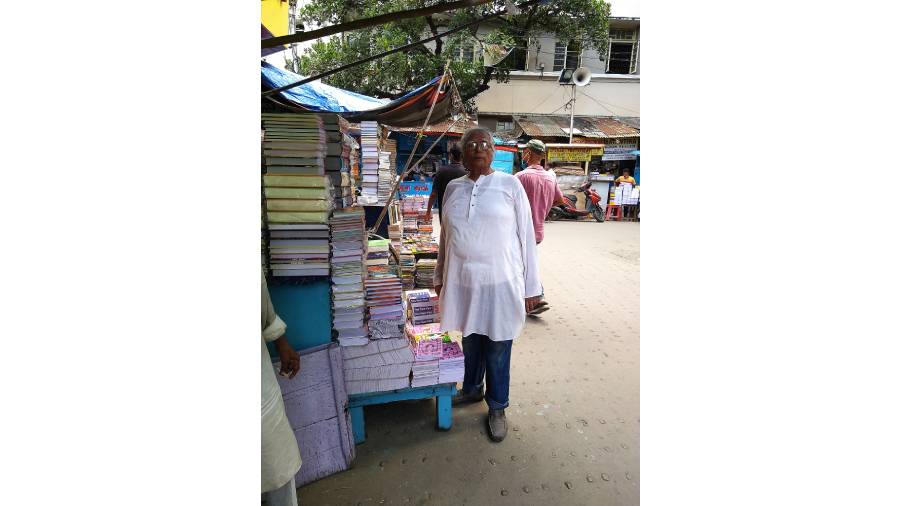

According to Dey, this was also the time when the problem of unemployment in Bengal was acute; a lot of people turned to selling books. By the mid-1960s, College Street was achatter with bookshops. Bankim Chatterjee Street, Radhanath Mullick Lane, Patuatala Lane, Ramanath Majumder Street, Tamer Lane, all were brimming with bookshops. Dey says, “Each and every household in College Street started opening up at least one bookshop. In the lane beside Presidency College mushroomed second-hand bookshops. But what was noticeable was the advent of hawkers.”

The 1970s brought with them their own turmoil. Bangladesh was yet to be born, and refugees were entering the city in droves once more. Dey continues, “College Street had witnessed the spectre

of Partition. This is where Gopal Patha fought and saved lives. The Calcutta riots had ripped open the heart of College Street. Before all that, this place had never babbled in communal language. It was a seat of culture. Id and Muharram, Kali Puja and Durga Puja, everything was celebrated here. Even during the riots, the people here stood up for their neighbours without even asking if they were Hindu or Muslim.”

In the 1990s, the letterpress went out of fashion and offset printing became the favoured mode. From being the intellectual’s haunt, College Street now became the crammer’s refuge. Shops selling textbooks, guidebooks and question papers started to come up. “Today one does not even know how many bookshops there are — 3,000, 5,000, 7,000,” says Dey.

As College Street burgeoned, so did the family sweetmeat business. The who’s who of the city would stop by. Dey says, “Artist Ganesh Pyne would stop here every evening between 7 and 7.30. Former CM Jyoti Basu and litterateur Samaresh Basu too stopped here. And once Gunter Grass dropped in.” Dey remembers watching his father chat up his famous customers.

“And if we must talk about adda and College Street why talk about my sweetshop, when the great Coffee House stands here,” exclaims Dey. He pauses, eyes fixed on nothing in particular, takes a deep breath and starts to say, “It is now all smoke and darkness and…” Then quickly adds, “Manna Dey’s song has come true.” He is referring to the musical legend’s nostalgia stoked number from the 1980s — Coffee House-er shei adda-ta aaj aar nei. The entire song is a lament for the Coffee House, for scattered friends, for lost youth and a broken adda.

The singer’s near namesake then says, “The ambience has changed. Intellectuals do not come this way. It is all darkness and smoke...”

Many of the College Street bookshops have closed down following the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. Dey’s sweetshop too closed down.

College Street-er shei adda-ta aaj aar nei...