Book: Hul! Hul! The suppression of the Santhal rebellion in Bengal, 1855

Author: Peter Stanley

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Price: ₹699

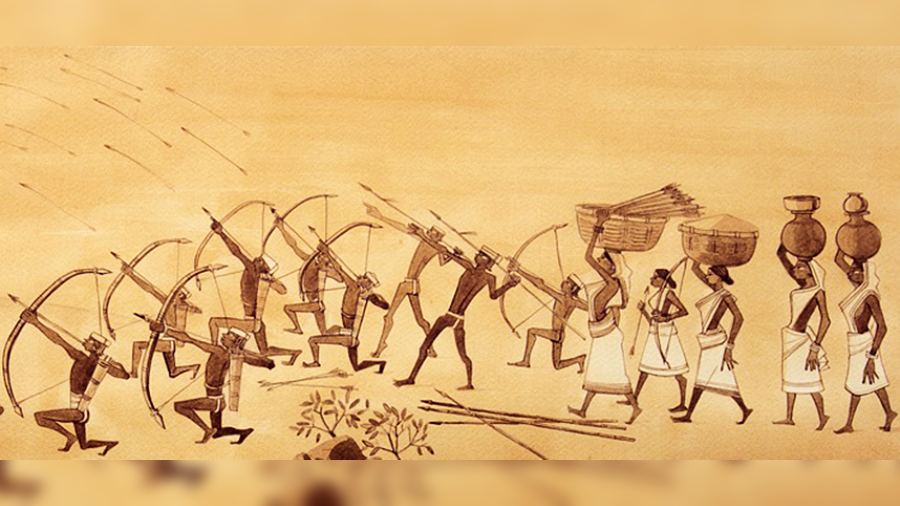

Peter Stanley does a commendable job of uncovering the neglected history of the Santhal Hul (rebellion) of 1855, considered as the most serious uprising the East India Company ever faced. In Hul! Hul! (Rebel! Rebel!), Stanley painstakingly rummages through archives that have remained unexplored to provide a detailed military, administrative and social history, thereby revealing the lives and stories of those who have remained in obscurity.

It is a travesty that the story of the rebellion is not better known. But this is not surprising given that history tends to be written by victors. The Hul was a natural culmination, a domino effect of oppressive events and discriminatory administrative-civil structures that meted out injustice to those considered to be the lowest on the rung — the adivasis. More than a rebellion against the British, the Hul was to expose the fault lines among the “natives” — a build-up of resentment against the mostly Bengali mahajans and merchants as well as foreign landlords owning indigo factories who treated the “native races” with disdain, employed Santhals as labour, and paid them measly amounts.

The Santhals formed a core part of labour in the early years of the East India Company government. The combined stress of displacement and exploitation produced a fertile environment for the creation of phantasms and supernatural signs, where religion and rebellion powerfully combined to turn into the Hul. As Stanley puts it succinctly, “Santals felt the weight of economic oppression and, mobilised by religious rhetoric, sought redress.” Reading the book, one wonders how not much has changed in the present day — the ones governing retain the xenophobic and patronising attitude towards their “subjects”.

Lower Bengal and Orissa had a history of uprisings, beginning with a peasant uprising in 1783 that has remained undiscovered by popular knowledge. This book becomes an attempt at narrativising the “subaltern resistance” and paves the way to connect the dots with other indigenous rebellions, thereby challenging the notion that between the battle of Plassey (1757) and the Sepoy Mutiny (1857), the colonists faced little opposition.

In India, history has been suppressed to suit the narrative of the powerful. Lack of documentation exacerbated by a casual attitude has ensured the loss of material history, of historically important places, and of thousands of stories. The memory of the Hul lives on among the people of Rajmahal, but not much has permeated outside of that territory.

Today, tribal communities face increasing marginalisation. Some could argue that the status of adivasis is worse than what it was in 1855, given their disempowerment by State forces and displacement because of corporate greed. In this light, the book does an important job of documenting adivasi resistance. Stanley is empathetic towards the Santhals who gave so much to this land and witnessed sweeping changes in the last 200 years. He also acknowledges the skewed nature of the book, since the bulk of the source material is from the British archives, but hopes that it would pave the way for Santhal voices to take control of their own stories.