Book- The Language Of Trees: How Trees Make Our World, Change Our Minds And Rewild Our Lives

By- Katie Holten

Published By- Elliott & Thompson

Price - £ 16.99

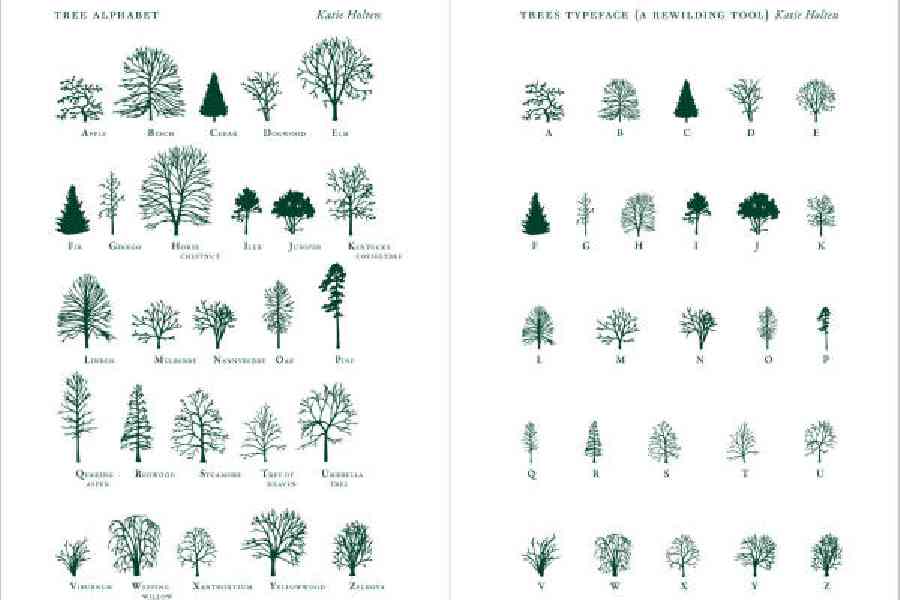

The Language of Trees is a testament — perhaps ironic, given its title and its content — to the lure of books in their physical form. If the matte, forest-green hardcover with a delicate illustration of a woodland gilded on it is not enough to entice readers, there is also the soothing green Essonnes and Garamond fonts of the text. The most alluring thing about this volume, though, is its design. Katie Holten has created a unique tree typeface (picture) in which each letter of the alphabet is assigned a tree according to the first letter of its popular name: ‘a’ is thus an apple tree, ‘b’ is beech, ‘c’ cedar and so on. Each of the contributions to the book is aesthetically set to this typeface — an enchanting, harmonious transformation from text to image — resulting in dense and lush groves, which are then used to illustrate the text. This is not to mention the other illustrations that dot the volume — leaves of different shapes, the shadow of a tree, botanical parts of plants, among other visual meditations on all things green.

The book’s design is unique just as its list of contributors is eclectic. Plato rubs shoulders with Radiohead and the words of the author, Zadie Smith, are reflected in the findings of the ethnobotanist, Jonathon Miller Weisberger, while Amitav Ghosh’s plea for climate action is echoed by Nemo Andy Guiquita, a Waorani indigenous leader from the Ecuadorian Amazon. The textual contributions themselves are diverse — quotes, poetry, essays, extracts from novels, press releases, Instagram posts, exhibition catalogues, interviews, scientific papers, recipes and natural remedies and other such musings are brought together to form an extensive archive of the many branches of human knowledge on the living world of flora that surrounds us. As with many anthologies, there are moments when the narrative arc feels like a long and winding trail through the woods. However, not only is there pleasure to be had in this unhurried, meandering path, but there are also frequent moments of wonderment along the way.

One such moment is Aengus Woods’ essay on Ogham — an early medieval alphabet that uses trees and branches for letters and is perhaps a predecessor of Holten’s tree typeface — in which history, myth, sociology, linguistics and visual arts coalesce into a fascinating whole. Anna-Sophie Springer’s essay on “The Library as Idea and Space” makes a tangible connection between trees and language, which is also what Ross Gay does in the Introduction, where he underlines that the proto-Germanic antecedent of the English word, book, is ‘beech’ and that such overlaps between the words for books and names of trees exist in several languages. The connection between books (language) and trees, though, is not always intimate. In “Speaking of Nature”, Robin Wall Kimmerer focuses on how the deployment of depersonalised language — pronouns such as ‘its’, for instance — makes a forest and a copper mine seem equivalent. Language, she writes, “encodes human exceptionalism, which privileges the needs and wants of humans above all others and understands us as detached from the commonwealth of life.”

Activism animates The Language of Trees and the theme of climate change crops up time and again — deservedly so. Pedro Reyes’ blog post on the Botanical Garden of Culiacán, Mexico, starting a programme where people surrendered their guns, which were then melted to make shovels that were used to plant trees, is a perfect example of citizen activism that this book champions. But the central question that animates and unites the 69 voices heard in this book is this: if trees have memories and can communicate, what can they tell us and, more important, are we ready to listen? The climate emergency demands that we learn the language of trees and speak on their behalf. In the Afterword, Holten writes that “[t]his book is a love letter to our vanishing world...” Indeed, it is, but it is also a call to action for those who still care.