Book: Going: Stories of kinship

Author: Keki N. Daruwalla

Publisher: Speaking Tiger

Price: Rs 499

Keki N. Daruwalla’s latest collection of stories, Going, would leave readers with an ache. The stories etch variegated lives — with the faintest of brush strokes — when the country was on the verge of Independence or just thereafter. The settings include tea gardens of Assam, ferries on the Brahmaputra, shikar expeditions in Shamsabad (now Hyderabad) or perhaps Parsi apartments and Bombay’s corporate world. Yet, in the end, they are not so different after all as they bring together distraught parents, children and grandchildren. Perhaps Keki the poet could use the lines of another poet to describe Going’s preoccupation with relationships between parents and children. As Khalil Gibran says: “Your children are not your children/They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself/ They come through you but not from you/ And though they are with you yet they belong not to you (“On Children”).

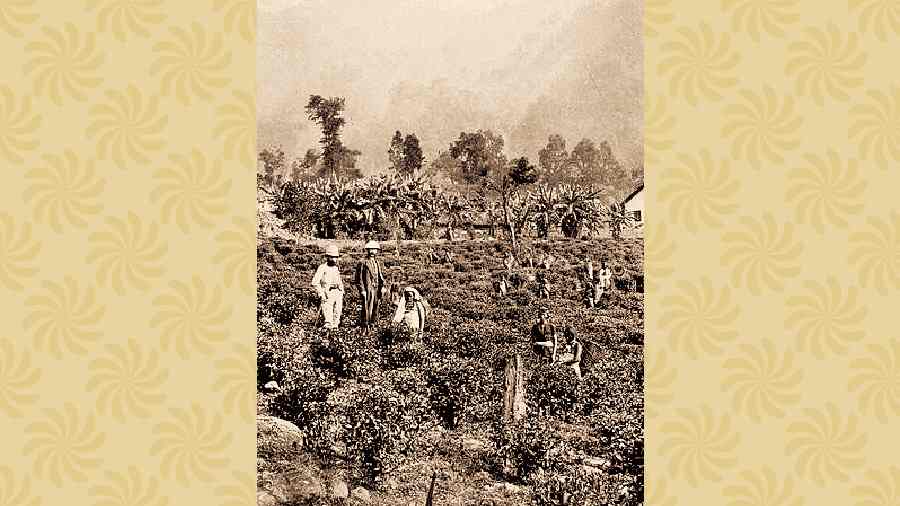

The “Brahmaputra Trilogy” is my favourite because it describes places and people I know. The narrative remains tenuous, and information lies beyond the readers’ grasp. Vikram appears to be a part of a trio that makes up a fighter group that reaches the Cuthbert Tea Estate, a tea garden earlier held by British planters. The reader is never told as to whether these three (especially Vikram who has a distinctive fair skin) fight for the cause of tea labourers or hold grudges against the exploitative, chaotic systems of Assam’s tea gardens. Clearly one among the three has a resentment that has been sustained. The bomb that, in all probability, Vikram explodes in the bungalow of the tea garden manager is his way of shredding the shroud of whiteness that he has inherited as a child born out of wedlock in the tea gardens. The manager, who is saved miraculously, is, however, an Indian and, therefore, not Vikram’s target. Is Leonid Campbell, the former sahib manager who had returned to India after the Second World War to wrap up British tea operations, Vikram’s father? The investigating officer thinks so. The incident evokes uneasy memories, such as those of Campbell’s relations with a coolie woman once his wife, Patricia, had left. The story is left inconclusive, raising suspicion and unease regarding the meaning of freedom.

Perhaps the most profound of the stories, “Bird Island”, describes the mysterious disappearance of a couple’s (Hemlata and Sudhakar) son. Nothing can explain the disappearance of Sukhdeo, an introvert. But a lot can explain Hemlata’s unwillingness for a police investigation given that it might lead to possible evidence of her son’s death. Much later, Sudhakar joins the nawab of Shamsabad on a shooting adventure. While the nawab shoots birds, Sudhakar captures them in photographs. He sees that the otherwise edgy birds are comfortable on a lonely riverine island even though it is inhabited by a human being. Sudhakar’s instincts lead him to the island and he confronts this strange hobo-like figure. There, the birdman's face — sunburnt, bearded, caked with dirt — lights up as Sudhakar utters the name, “Sukhdeo!”

The poignancy of these tales makes them worth reading.