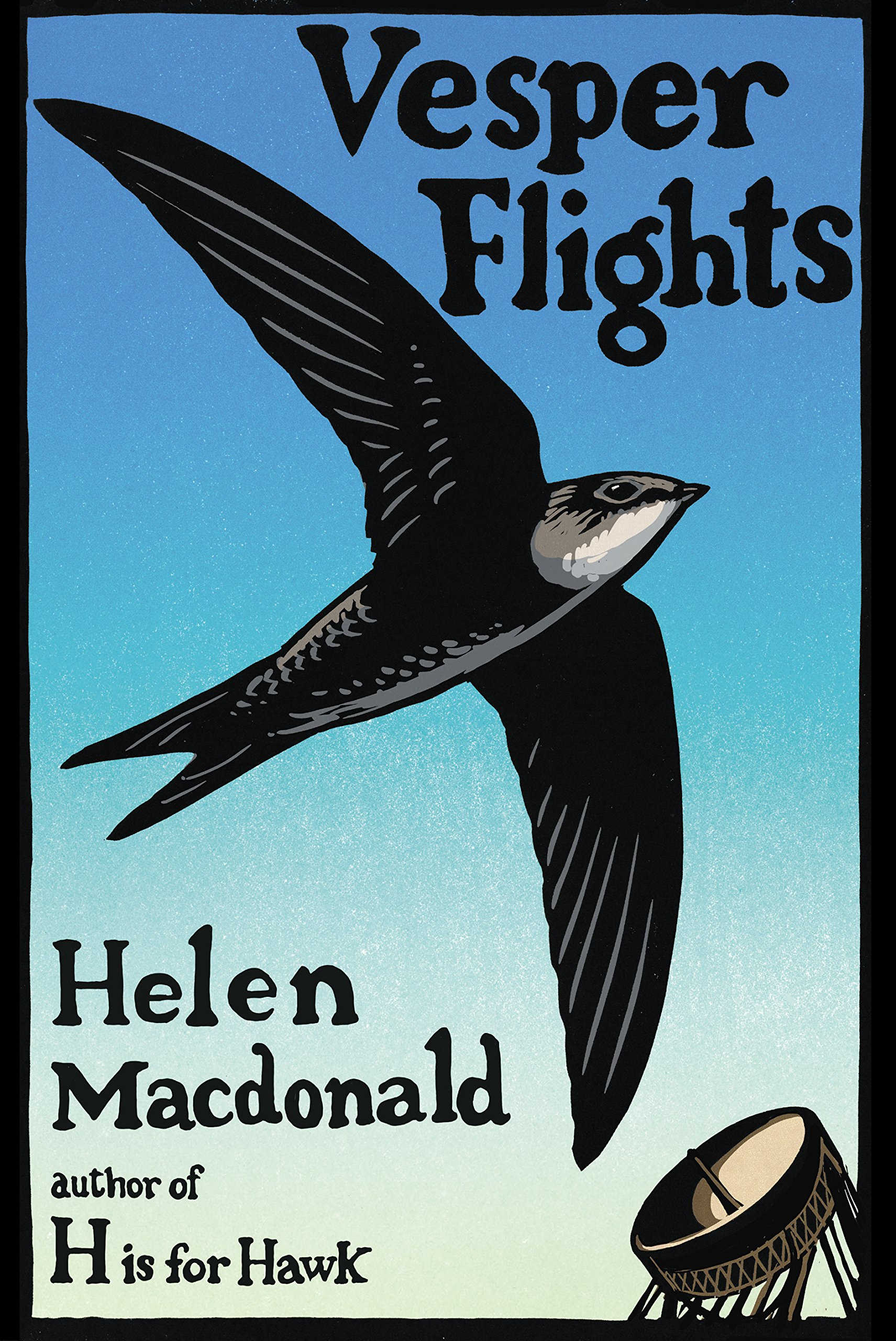

Book: Vesper Flights

Author: Helen Macdonald,

Publisher: Vintage

Price: Rs 799

Quite a few reviews of Vesper Flights mention Helen Macdonald’s hope that her book “works... like a Wunderkammer”. But it would be reductive to suggest that this volume of slim, searching — often searing — essays allegorically resembles a cabinet of curiosities meant to evoke a sense of strangeness and wonder. Vesper Flights is more than that. It is lyrical in style and philosophical in temperament, an embodiment of a deeper tryst. The book ought to be read as Macdonald’s continuing exploration of and search for meaning: what does it mean to ponder, love, be enchanted by a world — the world of mushrooms, ants, hares, deer, swans, wintry woods that Macdonald unveils slowly, delicately, delightfully — that is not quite like our own? The answer possibly lies in interrogating humanity’s stubborn inclination to impose its own thoughts, needs and meaning on the natural world that is being decimated by human depredations with a fatal consequence: climate change. Vesper Flights is a stimulating, intelligent, yet never haughty interrogation of the template of anthropomorphism that dominates culture and science.

Macdonald’s reflections on the limitations of science as she goes about her tryst to discover a new, meaningful engagement with the wilderness is particularly instructive. “We have corralled the meanings of animals so tightly these days, have shuttled them into separate epistemologies that are not supposed to touch.” This soulless disaggregation means that “scientists aren’t supposed to speak of magic”. Even though science’s role in computing the humongous scale of the Sixth Great Extinction cannot be substituted, it is the loss of the magic wand that has rendered science peculiarly impotent when it comes to making civilization commune with the losses that it is inflicting. And therein, Macdonald writes, lies the potential of literature. “The landscapes around us grow emptier and quieter… We need hard science to establish the rate and scale of these declines, to work out why it is occurring and what mitigation strategies can be brought into play. But we need literature, too; we need to communicate what the losses mean.” It is literature, not science, that can let us feel, sometimes presciently, “[O]ur experience of a wood… made of light and leaves and song” becoming “something less complex, less magical, just less,” when the wood-warblers are gone forever.

Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald, Vintage, Rs 799 Amazon

Furthermore, what science understands as benevolent intervention can, Macdonald argues, raise complex ethical dilemmas: “Increasingly, animals are seen not only as proxies for scientific researchers but also as scientific-research equipment functioning like sensors or probes. In one project studying climate change in West Antarctica… elephant seals with tags glued to their foreheads collect and transmit data… used for weather forecasting and climate change. This notion of autonomous biological-sampling devices confuses the distinctions between technology and living organisms, quietly erasing the animal’s agency.” Macdonald also problematizes the concept of wildlife reserves by marking their distance from the collective ecological consciousness: “If you start to see ecologically rich habitats as temporally separated from us, then the lack of wildlife in modern landscapes seems unremarkable.”

That words — the building blocks of literature — can foster empathy is proved by Macdonald’s prose that turns the mundane magical. Thus a young Macdonald, a solitary, socially awkward, bullied child, reaches out to touch a bird-dwelling through thistles and brambles with the full knowledge of nests resembling “bruises”, “… things I couldn’t help but touch”. In the essay, “Inspector Calls”, it is, again, the magic of literature that transforms an ordinary encounter into something enduring — like love and loss: “The bird and the boy stare at each other. They love each other. The bird loves the boy because he is entirely full of joyous, manifest amazement. The boy just loves the bird. And the bird does that chops-fluffed-little-flirting twitch of the head, and the boy does it back.”

It is literature, this kind of gifted writing, that can capture and communicate the essence and the beauty of the bond between man and animals.

Macdonald is also that rare writer who can fuse her mastery over language with a sparkling intellectual curiosity. Vesper Flights captivates — perhaps the comparison with the Wunderkammer is apt — by evoking a sense of wonder at the strangeness and the richness of our encounters with species. “Murmurations” describes “starlings rising from their roosts in pulsing circles, lapwings moving north along weather fronts… The whole sky etched livid… and the reflections of moving wings.”; “Deer in the headlights” explores the animal as a paragon of social — very British — conservatism, the stags attuning themselves to the symbolism of stability in a world spinning on change; “Swan Upping” embeds the bird on the body politic of nationhood and identity; “Winter Woods” — “wood and soil and rotting leaves, the crystal fur of hoarfrost and the melting of overnight snow...” — reassures us with their ability to compress hours, days and centuries into the time spent in their shadows.

It is plausible that Macdonald has, indeed, discovered the tenor of the language of conservation, a language that enables us to “think of animals as more than mere creatures, each living species at the center of a rich fabric of associations linking… matters allegorical, scriptural, proverbial, personal.”

A little bird — the Swift — may have helped.

“So I’m starting to think of swifts differently now… as perfectly instructive creatures. Not all of us need to make that climb, just as many swifts eschew their vesper flights because they are occupied with eggs and young — but as a community, surely some of us are required… to look clearly at the things that are so easily obscured by the everyday… Swifts are my fable of community, teaching us about how to make right decisions in the face of oncoming bad weather…