Book: The Language of History: Sanskrit Narratives of Muslim Pasts

Author: Audrey Truschke,

Publisher: Allen Lane

Price: Rs 699

Written accessibly for a non-specialist audience, Audrey Truschke’s latest monograph, The Language of History, is a timely intervention in an increasingly polarized world in which we find ourselves. It showcases the dazzling diversity in writings on Muslim rule in premodern India in a range of Sanskrit texts and inscriptions composed between the late twelfth and the early eighteenth centuries. The texts do not constitute a homogenous literary corpus; instead, individual works — dynastic histories, court chronicles, accounts of military victory, monastic biographies — were prepared by authors located in different geographical and historical contexts. Yet, what is common to all of them is that Hindus and Muslims are never imagined as two monolithic religious communities with irreconcilable differences between them. As Truschke demonstrates, Sanskrit intellectual history of almost six hundred years — from Prithviraj Chauhan’s military encounter with Muhammad of Ghur to the twilight of the Mughal empire — is an unfolding narrative of political and cultural integration of rulers who did not belong to the varna-based social order and who did not use Sanskrit to communicate political power, the two distinctive markers of early Indic kingship.

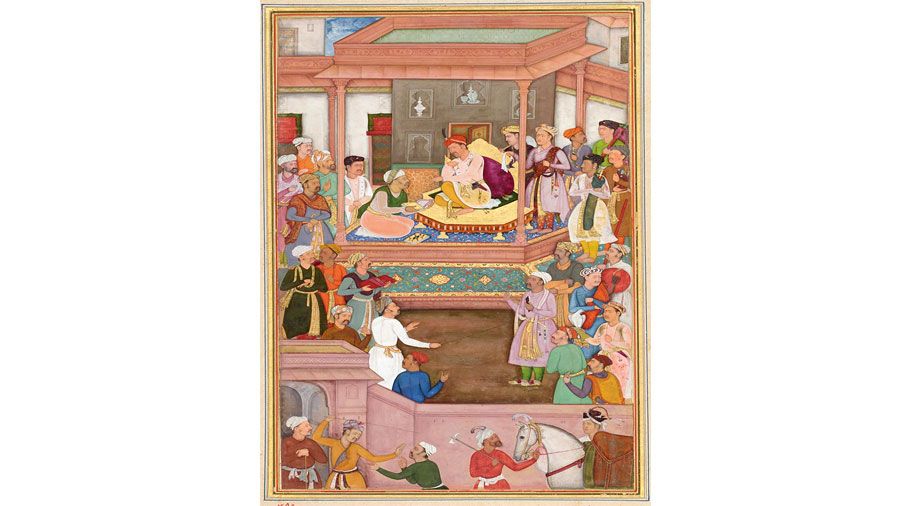

How this project of assimilation of Indo-Persian political actors was achieved can be gauged by juxtaposing two texts, which, in a sense, bookend Truschke’s own narrative. Prithvirajavijaya, a late-twelfth-century eulogy of Prithviraja, the Ajmer-based king of the Chauhan clan, was composed by his court-poet, Jayanaka, to celebrate the patron’s victory against the Ghurids, a ruling lineage from Afghanistan, who laid the foundation of the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in the early thirteenth century and consolidated the spread of Islam and Persian language and culture in South Asia. In this praise-poetry, Prithviraja is imagined as the righteous kshatriya king, an incarnation of Vishnu, who had been divinely ordained to restore the politico-ritual order of his kingdom sullied by Ghurids, the enemies who failed to speak Sanskrit properly and who flouted norms of Brahminical ritual purity by killing cows and drinking horses’ blood. Sarvadeshavrittantasangraha (‘Collection of Events Across the Lands’) was a partial Sanskrit translation of Akbarnama, the late-sixteenth-century Persian chronicle of the reign of Akbar, the third Mughal emperor, written by his vizier, Abul Fazl. It was created most likely in the early seventeenth century when the political histories of Mughals, the descendants of Timurids and Mongols of Central Asia, had begun to be written in Sanskrit. Representing a unique blend of Persian and Sanskrit literary traditions, its source of inspiration is a Persian text but its form follows that of well-known works of Sanskrit literary prose. The author-translator of this text, whose exact identity remains unknown, acknowledges the rich literary heritage of Persian, a language which had sounded like the cry of wild birds to Jayanaka a couple of centuries earlier.

The Language of History: Sanskrit Narratives of Muslim Pasts by Audrey Truschke, Allen Lane, Rs 699 Amazon

In the period between the composition of Prithvirajavijaya and Sarvadeshavrittantasangraha, the literary landscape came to be defined by the establishment of Persian as the dominant language of rule and the emergence of vernaculars, such as Kannada, Telugu and Gujarati, to name just a few. Truschke shows how intellectuals of this time writing about Indo-Muslim polity, most of whom were located in northern and western India, tapped into Sanskrit literary-aesthetic resources to creatively imagine particular rulers or dynasties. Among them was Gangadevi, the only woman author who figures in this book. One of the wives of King Kampan of the Vijayanagar empire, the most extensive and culturally influential political entity in precolonial southern India, she wrote Madhuravijaya to commemorate her husband’s victory in 1371 over the rival Sultanate of Madurai, a breakaway kingdom from Delhi Sultanate.

By paying close attention to the vocabulary employed in Sanskrit sources, Truschke shows that it is wrong to view the premodern past through a Hindu-Muslim binary. While the term, ‘Hindu’, came to be used in Sanskrit rather sparingly from the fourteenth century onwards, ‘Muslim’, too, was never the primary identifier for ruling groups professing Islam. Instead, poets and writers easily accommodated Persian-speaking Muslim rulers within the older, generic category of outsiders identified as mlechchha and yavana while periodically inventing new descriptors by adapting foreign terms, such as turushka from the Altaic for Turk and the Arabic-Persian derivatives, hammira and suratrana, from amir and sultan, respectively. The shared usage of the titles, hammira and suratrana, by both Muslim and non-Muslim rulers of medieval India clearly indicates overlapping conceptions of sovereign power by political elites of distinct religious affiliations.

This is not the first book to talk about either Hindu-Muslim encounters or ways of writing in Sanskrit in the premodern past. But by choosing such a wide canvas and building up on fine studies on these two themes, many of which have a regional perspective, Truschke is able to raise larger questions relevant to the historian’s craft, such as varied expressions of historical consciousness and the relationship between history and literature.