Book name: The Dream of Revolution: A Biography of Jayaprakash Narayan

Author name: By Bimal Prasad and Sujata Prasad

Publisher: Vintage

Price: Rs 799

Given the colossal range of his political life, penning the life story of a versatile socialist leader like Jayaprakash Narayan may seem an unenviable task for any biographer. Spanning roughly through the first eight decades of the twentieth century, Narayan’s political career frequently mirrors the major upheavals of his time — both in India and the world at large. The Dream of Revolution is an admirable feat. Instead of drowning the reader under an oppressive deluge of political challenges, the book manages to effortlessly navigate through the wide gamut of events unfolding in Narayan’s life with ease and dexterity. With its free-flowing narrative interspersed with meticulously researched anecdotes, The Dream of Revolution vindicates Narayan’s lifelong struggle against any form of stifling of dissent.

Although the biographers admit that “not much is known about Jayaprakash’s childhood”, they efficiently manage to link his early years with the gradual shaping of his political sensibilities in later life. The recorded circumstances are fascinatingly complex and varied: being exposed to the political churn at Saraswati Bhawan and at the residence of the historian, Jadunath Sarkar; a fascination for young revolutionaries and clandestine meetings with them through his classmate, Chhottan Singh; bunking classes to catch a glimpse of Bal Gangadhar Tilak; quitting college twenty days before his exams; and, finally, giving up the use of foreign cloth and footwear for simple, coarse khadi kurtas and handmade shoes.

Notwithstanding his early marriage with the fourteen-year-old Prabhavati in 1920, Jayaprakash, much against the wishes of his parents, took on the challenge of pursuing higher studies in the United States of America. In order to eke out an existence there, he did several odd jobs as an overseas student. However, it was his stint at the University of Wisconsin at Madison that addicted him to Marxism, igniting his revolutionary zeal for the rest of his life. He ultimately got his undergraduate degree from the Ohio State University in 1928. Following his return, he became a member of the Indian National Congress in 1929. Already inspired by Gandhi, he was now impressed by Jawaharlal Nehru whom he got to meet at a Congress session in Lahore.

An incorrigible optimist about the future of socialism in India, Jayaprakash formed the Congress Socialist Party, a leftist group within the Congress in 1934. In due course of time, as the “poster boy of democratic, radical dissent”, he got disenchanted with the Congress leadership. In spite of his best efforts, he repeatedly failed to convince his leaders of the necessity of a more aggressive path in the freedom struggle. His vociferous opposition to any form of Indian co-operation with the British during the Second World War led to his recurrent imprisonment during this period.

Jayaprakash’s disillusionment culminated in the post-Independence period when in 1952 he along with several other leading socialists quit the Congress to form the Praja Socialist Party. Ideological homogeneity, however, did not ensure a smooth run hereafter, as sharp differences with other party members soon made Jayaprakash totally disillusioned with any form of mainstream party politics. Fatigued with his earlier political endeavours, he now found sustenance in Vinoba Bhave’s Sarvodaya-Bhoodan movement, pledging to provide land for the landless.

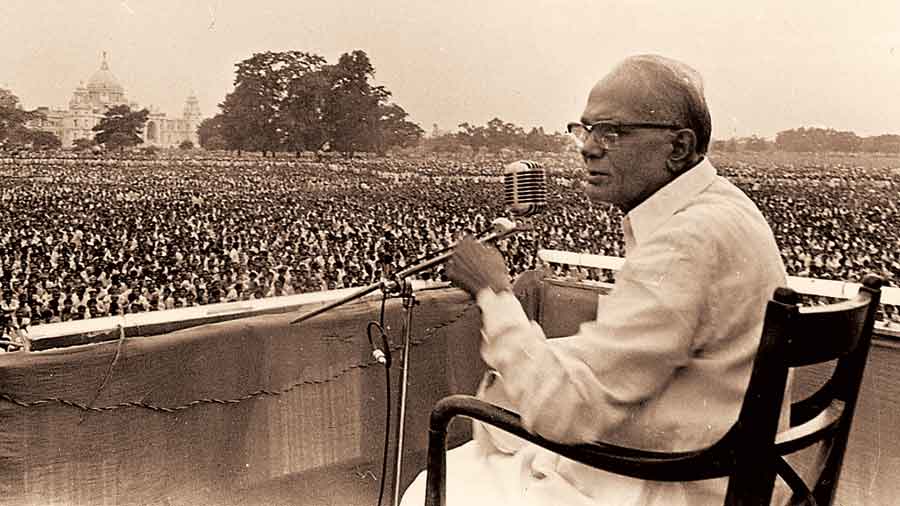

The last couple of decades in Jayaprakash’s life were as eventful and stormy as his days of pre-Independence activism. His isolated detention without any trial during the Emergency took a severe toll on his already worsening health. During his final days, in spite of being on dialysis, he continued to spearhead the combined fight against the authoritarian Indira Gandhi regime. The concluding chapter, “The Death of a Dream”, brilliantly chronicles the indefatigable resilience of the septuagenarian against all odds, oblivious to his rapidly deteriorating health.

The Dream of Revolution would not only engage those interested in the history of the Indian freedom struggle and post-Independence domestic politics but also those interested in the fascinating personal struggle between revolutionary romanticism and the grim ethical and political realities of life.