Book: Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story

Author: Yasser Usman

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Price: Rs 599

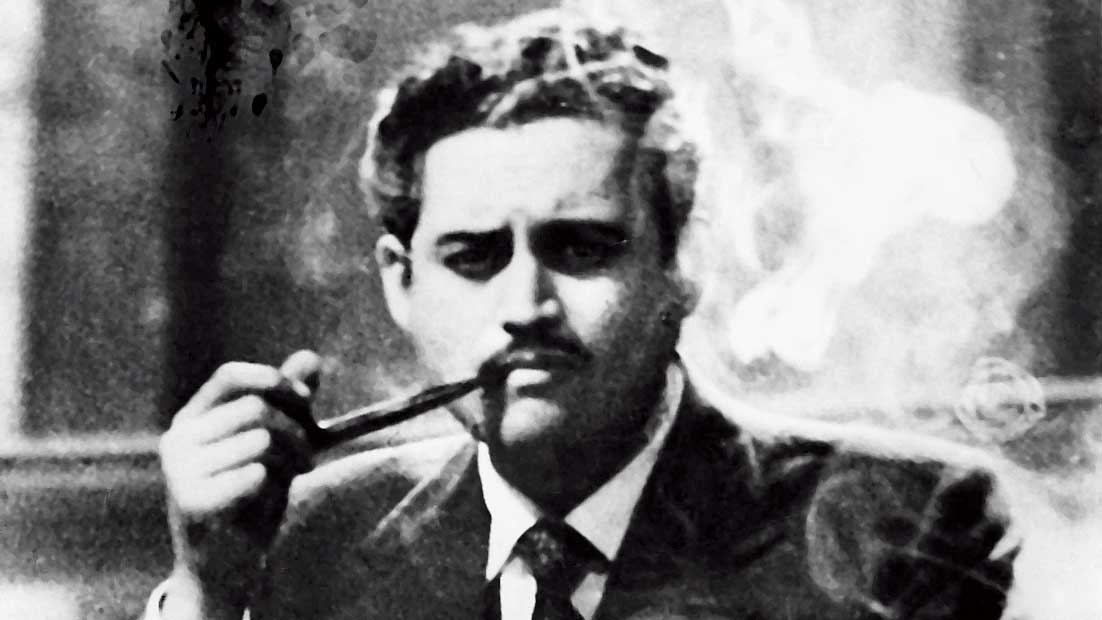

Guru Dutt died on October 10, 1964. He was 39. Whether he took his own life or it was an accident remains a mystery. Much like the man himself.

This mystery behind the man is what the journalist, Yasser Usman, seeks to uncover in his biography of the celebrated yet enigmatic film-maker — the “unfinished story” as he calls it.

This is a deviation for Usman, whose biographies thus far (of Rajesh Khanna, Rekha and Sanjay Dutt) have all been ‘untold stories’.

In a sense, Usman has told a number of ‘untold stories’ in his bid to find a closure to the ‘unfinished story’ that was Guru Dutt.

The book begins in Berlin on June 26, 1963, the day before the screening of Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962) at the 13th Berlin International Film Festival. Guru Dutt and Waheeda Rehman, two of the three lead actors, were present along with the director, Abrar Alvi. The Berlin trip was not a happy one for Guru Dutt. The film was rejected outright with the international audience failing to connect with its very Indian theme.

On a personal front, the blow was even more severe for Guru Dutt. Waheeda, his protégé and over whom Guru Dutt’s married life with the singer, Geeta Dutt, had deteriorated over the years, conveyed the end of her relationship with the film-maker. The two never met after Berlin.

On the way back to India, Guru Dutt sat in one corner of the flight and drank through the journey.

Usman sets the tone for the book with this episode. The subsequent chapters, grouped into 15 sections, 14 of which are alternately titled ‘Beginning of a Dream’ and ‘Destruction of a Dream’, narrate the story of a man whose creative talents found expression at an early age when the family moved to Calcutta, his stint at Uday Shankar’s dance school in Almora which shaped his film-making instincts, his struggles to find a place for himself in the world of cinema, his chance meeting with Dev Anand that was to change his fortunes, his success as a director of breezy crime thrillers while his inner self yearned to do something more meaningful, which he did with the poetic Pyaasa (1957), and his utter dejection with the box office debacle of what many now consider to be his magnum opus, Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959).

Usman tells the story going back and forth in time to show how the creative man gave shape to his dreams but, at the same time, his inner conflict, or kashmakash, destroyed these dreams. He didn’t even spare his palatial Pali Hill bungalow, which he demolished on a whim.

Much of the conflict arose from his tempestuous marriage to Geeta, a hugely talented and popular singer coming from an aristocratic Bengali family. Early on in their courtship she was by far the better-known half of the couple, earning in thousands while he was struggling to find a regular income; she was an extrovert who loved parties and her drink while he was essentially a loner who preferred his own company. This was the precursor to Guru Dutt’s future battles with depression and alcoholism which Usman has dealt with in detail, including his suicide attempts.

His relationship with Geeta also exposed Guru Dutt’s hypocrisy — in his movies he spoke about “working women” and questioned archaic traditions while in his personal life, he wanted his wife to give up her singing career and follow the conventional values of marriage and motherhood. Usman cites an interesting passage from Binidra, the recollections of the author, Bimal Mitra, of the time he spent with Geeta and Guru Dutt to illustrate this.

He was also supremely indecisive. As the owner of a film production company, Guru Dutt was conscious that he was responsible for the lives and livelihoods of all his employees. Yet, his creative urges meant he often couldn’t decide what he wanted. For example, he would start making movies on a whim, spend lakhs on them only to abandon the projects. Two of these find mention in the book, Gouri (which was to have been the screen debut of Geeta) and Raaz (based on Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White; this was to have been the debut of R.D. Burman as composer). Usman has quoted from Eka Naukar Jatri, the memoirs of the writer, Nabendu Ghosh, who worked on both these shelved projects.

Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story by Yasser Usman, Simon & Schuster, Rs 599 Amazon

Guru Dutt was also a film-maker who was possibly ahead of his time, as judged by the reaction now to Pyaasa, Kaagaz Ke Phool and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, the last of which he didn’t officially direct. Images of Waheeda’s bewitching smile as she beckons the poet, Vijay (Guru Dutt), with “Jaane kya tune kahi” in Pyaasa, the play of light (brilliantly shot by the gifted cinematographer, V.K. Murthy) in Kaagaz Ke Phool with Geeta-S.D. Burman-Kaifi Azmi’s “Waqt ne kiya” resonating in the background, and Meena Kumari’s eyes in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam as she croons “Na jao saiyyan” flash before us. Guru Dutt was a master of filming song sequences, which he often used to take the narrative forward. His films were known for their music, be it O.P. Nayyar or S.D. Burman or even Ravi in the blockbuster, Chaudhvin Ka Chand, which he made after the debacle of Kaagaz Ke Phool.

Usman has done painstaking research as a biography of Guru Dutt demands, sourcing information from magazines, newspapers and books such as My Son Gurudutt written by the film-maker’s mother, Vasanthi Padukone. One drawback for researchers is that all these were written after Guru Dutt’s death and very little contemporary written material is available on the film-maker, except for gossip pieces. As a result, almost nothing is known of what Guru Dutt’s or Geeta Dutt’s reactions were to many incidents that touched their lives.

The narrative is also enriched by the warm recollections of Guru Dutt’s younger sister, the famed artist, Lalitha Lajmi.

One quibble with the book is that it could have been better edited — there are quite a few spelling errors, for example, the name of the actress, Shakila, is spelt differently on the same page. Maybe the later editions will rectify these. Also, an index would have helped for cross-referencing.

The final section of the book is titled ‘1964’, the year Guru Dutt died, possibly from an overdose of pills. For many aficionados, this was the-day-the-music-died moment of Hindi cinema when one of its most creative auteurs passed away leaving behind many unanswered questions and unfinished stories. Usman’s book is an honest effort to portray the man behind the auteur even if some stories will always remain unfinished.