Book: China’s Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism

Author: Rana Mitter

Publisher: Harvard

Price: Rs 2,815

Rana Mitter’s fascinating account of the politics of memory, history and history-writing of China’s experiences of the Second World War offers many insights. As China seeks to claim a firmer membership to the basis of the construction of the international order, it seeks a more proactive role in the reconstruction of an event that was central to the founding of the present global order: the Second World War. As the Cold War ended, and China looked for a new footing on which to understand its relationship with the wider world, the public memory of the Second World War, although consistently present in the consciousness of its society and people, acquired a new prominence. Rewriting China’s history of the Second World War, therefore, also provided a platform from which a narrative about collective and unified patriotism could be forged on the basis of the crafting of a new understanding of a historical episode while also partaking in a global international effort.

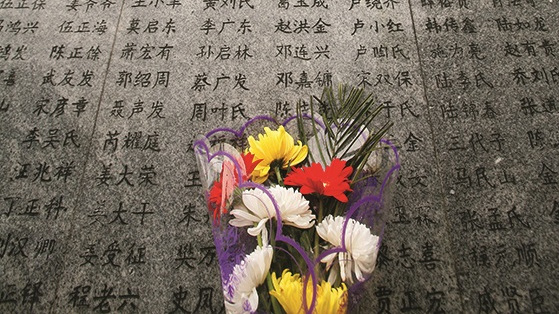

Mitter offers a richly textured account of the politics of history, memory and international relations by taking us through an analysis of the different ways in which China’s memory of the Second World War is being harnessed to serve a broader purpose. The experience of the War is an important ingredient in the shaping of public memory and a sense of collectiveness — present in its museums, mainstream films and soap operas as well as in a lively debate about the content of school textbooks. During the 1980s, the Chinese government escalated a confrontation over the question of the wartime experiences of Southeast Asia by charging that Japanese textbooks minimized the atrocities committed by Japan on China. Mitter notes, for example, “The commemoration of Japanese war atrocities in the Nanjing Museum contrasts sharply with the lack of official memorialization for other events of mass violence and death in recent Chinese history, such as the Civil War (1946-1949), the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). These other events are sometimes remembered at one remove, through the acceptable lens of memory of the war against Japan, whether in private museums or through films and other creative works.”

Actors attempting to take on these questions have discovered complex answers. For one thing, they take on the labels of perceived ‘victors’ and ‘losers’ of history and have to rearrange the sequencing in which they carry this out. Indeed, Mitter points out, part of this exercise also involves its present leadership confronting “… the awkward reality that the regime that was involved in various aspects of China’s postwar settlement, including the Bretton Woods discussions, the establishment of economic and social organizations, and the war crimes trials, was the Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek, not the Communist government of Mao Zedong.” In attempting to co-opt the internationalist legacies of the previous regime, the leadership in China is also seeking to reconcile with, and redress, the difficult legacies of victories and defeat during the course of its civil war.

Pulling at this thread also involves the evaluation of several complicated themes in the writing of a global history of international relations. For one thing, it provides an added dimension to comprehend how a ‘non-Eurocentric’ understanding of international relations should be developed: is this about developing a different, civilizational chronology, or can it also be a tool through which the European understanding of the twentieth century can be further built upon? Does this kind of recounting of the past also enable the insertion of other, non-European, or previously colonized (or informally colonized, as the case may be) actors who can be accorded a central role? And moreover, when this is done, does the end result enable a revision and correction to the way in which the world order was understood in the past?

China’s Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism, by Rana Mitter, Harvard, Rs 2,815 Amazon

This is also complicated by the fact that the memory of the Second World War in Southeast Asia is not an abstract matter —it doesn’t concern pre-historical matters whose actors have now safely died and been forgotten. The textbooks controversy, for instance, in how the experience of the War is commemorated in Japan and China, highlights this particularly clearly. Commemorating the Second World War and China’s war against Japanese aggressions during the 1930s also offers the politically convenient device of manufacturing a past in which an outsider enemy is defeated by a united mainland.

Yet, this was a complicated question, bringing to light a critical difference between the post-war experiences of Asia and Europe. While the politics of the Second World War found a firmer kind of closure in the establishment of institutions such as NATO and the World Bank that helped it clearly on the path toward post-war recovery, this pattern of post-war recovery was markedly absent in the Southeast Asian theatre, and the claimants of the legacy of ‘victors’ of the war, therefore, is still up for grabs.

With China claiming a stronger presence in the shaping of the post-war world, this historical episode provides a valuable platform onto which a number of different contemporaneously useful narratives can be fashioned: an old sense of unity and patriotism in the mainland which was always opposed to outsiders; an important voice in the shaping of the international order; and an opportunity for reconciliation and diffusing the differing claims of the nationalist governments.

Is all this, then, the process by which a revisionist power is trying to create new norms, or merely trying to use existing ones for its own purposes? In answering these questions, the book provides compelling insights into how norms — even Eurocentric and colonially-informed ones — are not static: countries not merely accept them and their ensuing understanding of the international hierarchy and their own lowly positions within it but, rather, can use the same vocabulary to further perpetuate their own objectives. Indeed, as this book reminds us, it is important to have a more nuanced understanding of exactly how different Asian countries went about navigating the European dilemmas of the twentieth century on their own terms for in grasping the process in which this is shaped, we can also appreciate how “Whether we realize it or not, we are all living in China’s long postwar.”