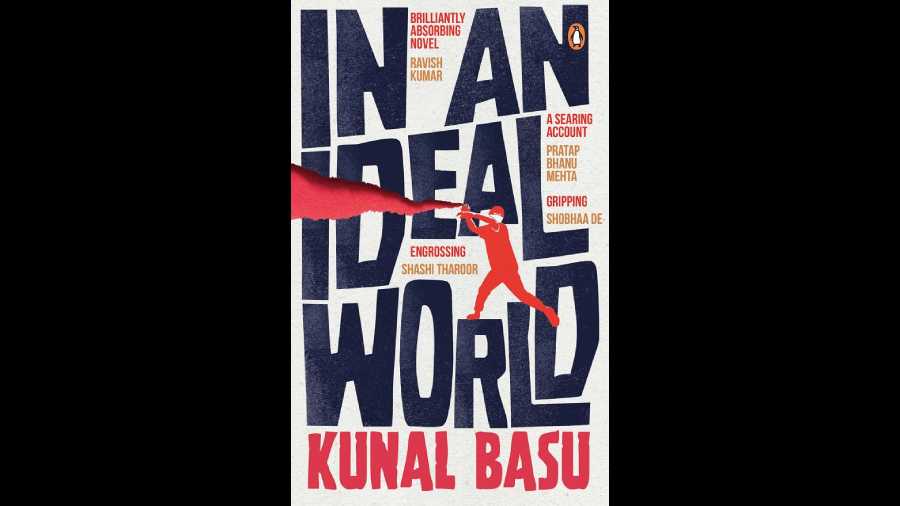

You may never have read a murder mystery like this one. Kunal Basu’s new novel, In an Ideal World, is the story of a student who gets brainwashed by his teacher into killing another student. But the mystery lies deeper.

In this suspenseful detective novel, the reader stands with bated breath alongside the parents, as they unravel the answer. We ask what prompted a teacher to incite his student to violence. We ask what prompted the police to cover up the murder as a missing person case. We ask what prompted an ordinary middle-class child to become a killer.

The parents grapple with fiendishly complex investigations involving religious fanaticism, kidnapping, murder, arson, and vigilante gangs. On the surface, this is a simple whodunit, but the psychological depth of the novel is far out of the realm of simplistic detective fiction.

It is a unique exploration of treacherous student-teacher relationships, a stunted family life, and a violence-prone state.

It is a brave offering by Basu, in a long and ongoing series of bestselling novels, at a time when we are all wrestling with the demons of a state that has turned on its own.

I am a professor at New York University and struggle with the same questions as I witness with horror the gun violence on school and college campuses across the US.

This Q and A with Kunal may provide some insights and understanding that may change the course of our actions.

In an Ideal World is a racy detective novel set in the middle of student politics.What is the crime that is the centre of the plot?

A young Muslim student, Altaf Hussein, has disappeared from his college campus. The authorities have washed their hands off the matter, denying his mother a proper enquiry. Rumours claim he has gone to fight the jihad in Iraq. More sinister rumours have him tortured and murdered for opposing the nationalist students who are on a rampage to create a Hindu homeland in India, driving out liberal supporters like Altaf and their decadent ideals. Was Altaf a victim of political and religious hatred? The detective work is undertaken by an unlikely duo: Joy and Rohini Sengupta, the parents of Bobby — the leader of the nationalist students, who is a prime suspect in the abduction. The twist in the tale lies in the fact that Joy and Rohini themselves hold liberal values and are shocked by the possibility that their son might have crossed over to the other side of the ideological divide and committed such a heinous crime.

Is your novel fact or fiction?

Fiction derived from a real incident. In 2016, a JNU student disappeared from his hostel, and hasn’t been found till date. There was considerable furore at that time, then he was, sadly, forgotten. Such cases of kidnapping, unjustified imprisonments and harassment of individuals suspected of anti-national activities, is now commonplace. The State demands unalloyed allegiance in the name of patriotism. Dissent is equated with treason. The prevailing climate of intolerance provoked this novel, which, ultimately, is a work of imagination. It enters, through the vehicle of fiction, the various worlds that coexist in our midst — that of the parents, the students, the political recruiters, the intellectuals and thugs, the perpetrators and their victims. Which is the real India? It asks and prompts the readers to find their own answers.

Like your other novels, you do not romanticise any situation or relationship, not even that between parents and children. Why is that so?

A lot of mystery and intrigue lurk within reality. We think we understand someone intimately, but then critical incidents might reveal a dimension we hadn’t ever considered. Like that between Bobby and his parents. Or, when Joy meets Bobby’s diabolical guru — Dadhichi. Everyday events too hold the key to revealing deeply held trauma, like when Joy, Rohini and Bobby go to a movie, and Bobby almost lynches a petty thief afterwards. Then, there is a party scene in the novel, where casual conversation between the guests exemplifies the chasm between their politic and lifestyles. A seedy bar, a building site, a religious procession, or a train journey may be seen as staging ground for life’s profundities. I haven’t felt the need to unnecessarily import elements into reality, simply search for what lies unnoticed.

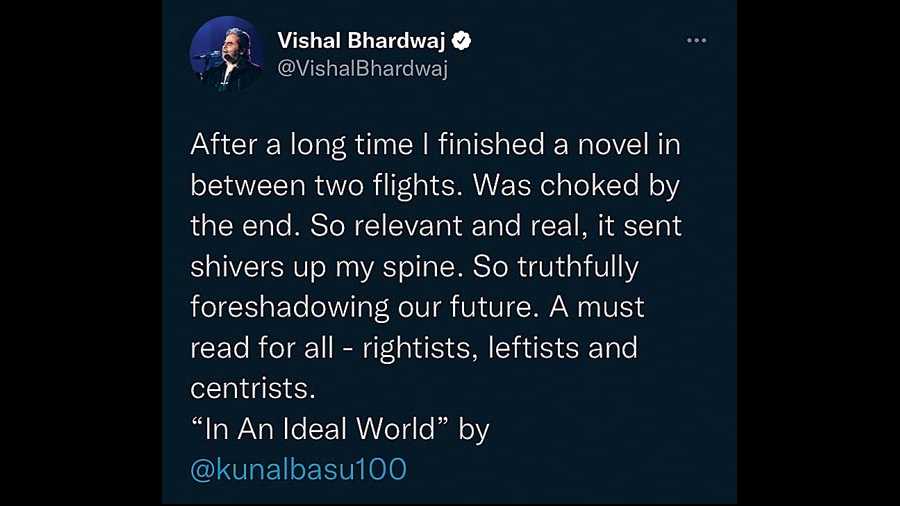

The book caught the attention of Vishal Bhardwaj who tweeted some poignant words about it.

Did you hit upon any profound insights as an author while digging into the motives of the crime, on behalf of your protagonists?

Several, actually. While I was aware of the broad contours of the crisis — political and psychological — bringing them home in fiction led me to investigate why and how a young person might be swayed into the politics of extremism. For one, I realised that there is a fine line between mentorship and brainwashing. Joy and Rohini didn’t try to indoctrinate Bobby with their views, wished him to find his own way in this world. They were hands-off parents. The absence of any guidance, though, left him with a blank canvas, which was fertile soil for the seeds of fanaticism to take root. Secondly, Bobby’s aversion to books, except those that helped him to achieve narrow academic goals, left him bereft of empathy and understanding of the multi-layered human condition. This is emblematic of our times. The Byju’s model of learning might create academic toppers but fail to build a healthy society. Thirdly, I recognised the value of courageous conversations, which might lend a constructive purpose to our disagreements.

What are the universal themes in your novel that could be true today, in the UK or USA?

Extreme nationalism is not a virtue, it is and has always been the bane of humankind. In the name of preserving a nation, it ruptures its parts, replaces hope with ugliness. For historically diverse nations — like India, the UK, USA as well as the continent of Europe — imposition of a religious or political creed would be dangerous. The resulting conflict won’t be simply limited to ballot boxes but spill out into our streets and families. Like a two-headed snake, it’ll devour itself.

Where does resolution or redemption lie?

Not in more vitriol. It calls for abandoning social media diatribes. We have gone as far as we can go in offering sophisticated counter-arguments to those with whom we are in disagreement. The “other side” simply isn’t listening. Neither will electoral victories settle the dust. Today’s losers will be tomorrow’s winners and exact their revenge. State terror or violent revolutions too have a poor track record of eliminating dissent. I believe we have focused too much on winning the war with our minds. It’s time to appeal to the heart, which might still harbour the spring of all that we cherish as humans — empathy, compassion, fraternity, and forgiveness. I am a big believer in the arts as a unifier. Just as Picasso’s famous lithograph of the dove held out hope to entire generations of Europeans after WWII, Attenborough’s Cry Freedom reduced both black and white audiences to tears, Israeli-Palestinian theatre for peace lit a tiny candle in that ravaged land, we must break the culture of hate with the counter-culture of the arts. That, and our engagement with service towards the most disadvantaged — refugees, victims of trafficking and climate change — might hold the key to atonement and redemption.