She sifted through the Delhi Art Gallery or DAG’s database for six months. “I went year by year, beginning with 1947 and worked backwards till the 18th century,” says Mrinalini Venkateswaran, who is a historian at England’s Royal Holloway.

The end product is the exhibition “March to Freedom” presented by the Indian Museum in Calcutta and DAG.

The exhibition has been structured around eight themes. Each represents what Mrinalini calls “an arena or stage” on which the anti-colonial struggle played out. She tells The Telegraph, “We see (in the exhibition) how the arts as a whole, from painting to cinema; the economy and the ordinary people driving it; public spaces and the public use of it; colonial institutions like courts, museums and universities, infrastructure, notably the railways; and colonised disciplines such as history and art history, were all re-purposed and re-imagined as sites from which to resist colonialism and shape an independent nation.”

There is a section called Battles for Freedom. It includes an 1802 painting of Tipu Sultan by Henry Singleton, which shows a ferocious Tipu with his sword drawn back confronting a British soldier. According to the caption, this style is known as history painting. There is a painting of the Battle of Chillianwallah — fought in 1849 between the British forces and the Sikh army in undivided Punjab’s Chillianwallah region. The watercolour is by Henry Martens and depicts a battle scene. “Both the East India Company and the Sikhs claimed victory in the Battle of Chillianwalla. Despite claiming victory, British sources recorded that it was a very difficult battle to win,” reads the caption.

Apart from these, the section has landscapes. Military artist James Hunter’s painting Seringapatam shows a procession of men, one elephant and some horses winding their way through a serene landscape. It gives no indication of the Indo-Mysore hostilities that spanned three decades, from 1767 to 1799, and involved the British, the French, the Dutch, the Mughals, the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Marathas, Travancore and smaller southern kingdoms... James Ross’s View of Lucknow with the twin minarets of the Asafi mosque and the harvested crop in the foreground hints at the fact that the East India Company’s Oudh fixation had to do with its bounty.

Artworks on water and waterways make up another section. Mrinalini, who apparently struggled to find appropriate visuals for the theme Traffic Of Trade, says, “I wanted to cross that inward-looking narrative of nation as a concept. I was wondering how to get across these centuries in history and situate them on the global stage. An offhand comment about ‘sea as a stage’ put things in the right perspective.”

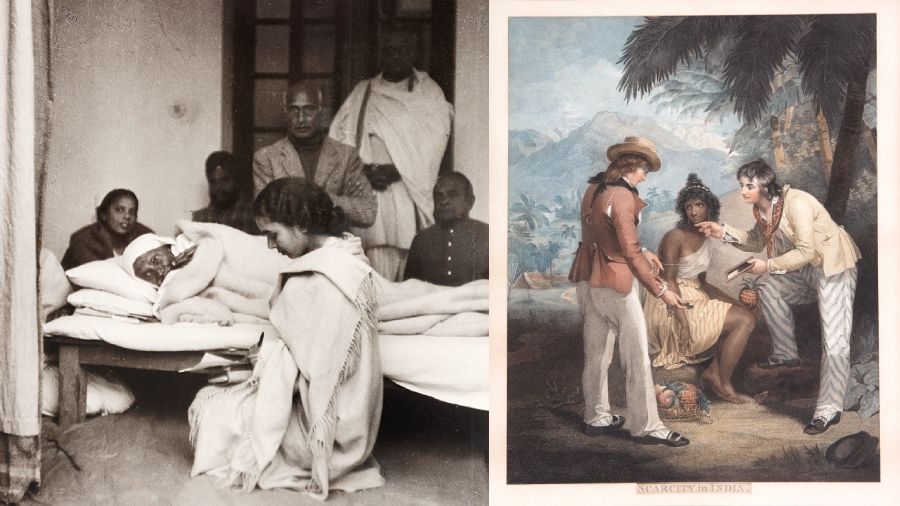

(Left Picture) Cartier-Bresson’s photograph of Gandhi at Birla House during his last fast.; (Right Picture) Singleton’s Scarcity in India DAG

Mrinalini has used DAG’s collection of contemporary Indian artists, such as Govardhan Ash and Haren Das. along with 18th-century British painters like Charles D’Oyly to construct the freedom struggle narrative through maritime history. An untitled watercolour by Ash shows a ship carrying cargo. You could read it as being representative of maritime trade of not just goods but also humans as indentured labourers. These labourers were sent by the British in India to their colonies in the Caribbeans, Fiji and other places. Das’s Ganges And Fishing depicts ordinary people and their lives around water. But the most surprising exhibit here is a vibrant untitled painting of a boat by Chittaprosad.

A pair of prints of Henry Singleton, Scarcity in India and British Plenty, represents the drain of wealth theory. Print 1 shows a village girl flanked by two European men. Print 2. Two white men with a white woman. “These two work at so many different levels — of art, of economic argument, of gender relation, of race relation,” says Mrinalini.

Discovering India with the Indian Railways has been a dominant narrative in cinema, television and other popular media. Gandhi’s travels through India is well documented. See India, another theme in this exhibition, is as much about travel as about the popular images of India in circulation. Posters of Sarnath, Ellora, Shimla, Gersoppa Falls, the Mahabodhi Temple, a poster in Devanagari script advertising cheap round rail tickets, a street scene of Lahore, Kalighat temple constitute the publicity and advertising material of the railways.

Mrinalini has not forgotten to include from sites of history such as courts, jails and secretariats. There are posters of Gandhi and sculptures of Bose, Tagore, Periyar, Patel, Ambedkar, Vivekananda, Tilak, Rajagopalachari, Zakir Hussain and Rajendra Prasad. Photographs of the last moments of Gandhi taken by Henri Cartier Bresson. A series of Chittaprosad’s ink on paper done in 1946-47 and unsparingly critical of both Indians as well as the British.

In the Shaping the Nation section, viewers are asked to write down personal stories of Independence as they may have heard from their grandparents and their relationship to the freedom movement.

Says Mrinalini, “I knew that the Indian Museum would have a wide cross-section of audience. So I used a variety of objects in a fun way, a visually eclectic way of telling a story.” She adds, “To turn this into a didactic history lesson was never the idea.”