I don’t know how you regard bats in Bengal. But in Telugu culture they are considered inauspicious, negative creatures.” That was Chinnaiah Jangam, associate professor at Canada’s Carleton University, who has translated into English the 1941 poem by Telugu Dalit poet Gurram Jashuva. Gabbilam: A Dalit Epic was published by Yoda Press this year.

Gabbilam means bat. Jangam continues, “Jashuva read Meghaduta and he inverted it.” Kalidasa had chosen the cloud to be the messenger of the yaksa pining for his beloved. Jashuva chose the bat to tell the story of Dalit life to India standing on the threshold of Independence and to the maker. The lines run thus: “When you hang upside down inside the temple/You will be closer to the ear of the God Shiva/Make sure the priest is not around/When you recount the story of my life.”

The past few years have not allowed urban India to ignore the reality of caste. A lot of it has to do with the way information circulates; videos, social media and WhatsApp forwards seep into gaps between knowing and not-knowing. That explains the easy familiarity with Una and Hathras, Unnao and Kathua, even among those who are unsure of the issue at the core of each. The same set that will tell you they have never heard the D word bandied about so much before. D as in Dalit. And yet Gabbilam is proof that the Dalit experience has remained unchanged, more or less; mostly that of victimhood and silences.

But Gabbilam’s protagonist, the Dalit, is a heroic figure. In the preface to Part I, Jashuva writes, “The protagonist in Meghaduta was sentenced to one year, but my hero was sentenced from birth without any end for generations.” In 2016, Rohith Vemula wrote in his suicide note: “My birth is my fatal accident.” Vemula, a Dalit student of the University of Hyderabad, had been suspended for raising issues under the banner of Ambedkar Students’ Association.

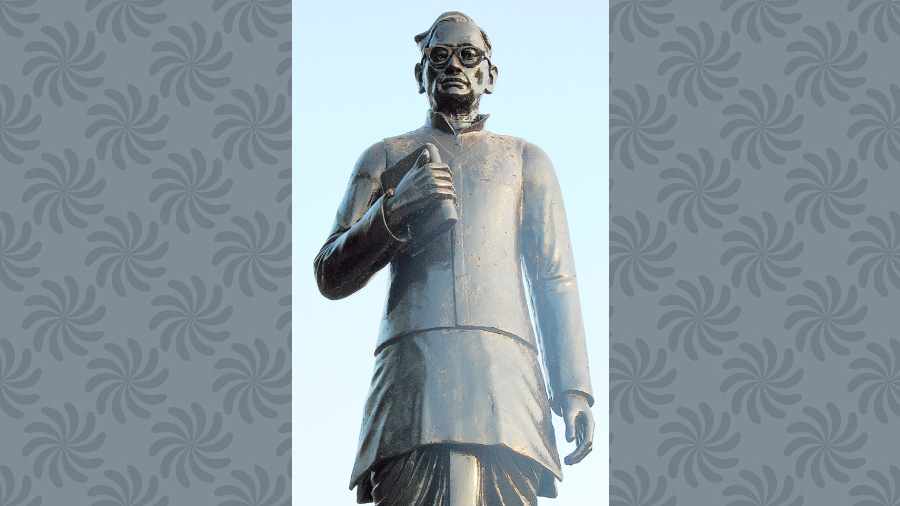

The heroism of Gabbilam’s protagonist derives from its creator. In a Facebook post from 2015, Vemula wrote: “Mahakavi Gurram Jashuva (1895-1971) was the first compelling organic Dalit voice in Telugu literature, who exposed the hypocrisy of caste ideology…” Jashuva writes about himself, “I will not be bound by caste and religious lines…/I am a universal human being.”

Jashuva’s universality is embedded in his geographical context. He was born in Vinukonda village of Guntur district in the Palnadu region of Andhra Pradesh. Jangam writes in the Introduction how after the decline of the Mauryan empire, the Satavahanas ruled this region, Jainism and Buddhism flourished here, and after the Satavahanas, Brahminism emerged as a counter revolution. One of the proclaimed issues for the famed Battle of Palnadu (12th century) was the decision of the minister of the Haihaya king to open the Chennakesava temple to all castes.

Eight hundred years later, when Jashuva was born here, newer characters had entered and thickened the old plot. “Christian missionaries made education accessible to Dalits and other oppressed castes. And unlike other provinces, in southern India non-Brahmins spearheaded the anti-Brahmin movement during colonial rule. After all, most of the revenue came from them,” says Jangam.

Jashuva’s mother, who belonged to the Madiga or shoe-making community, was one of the first Dalit women to go to the American Baptist Mission school. There she met his father, a Shudra. They fell in love, married and at some point converted to Christianity. Telugu Dalit writing, the earliest of which dates back to 1910, was in the language used in everyday life. Jashuva always wanted to learn Sanskrit and despite many rejections, he found a tutor. Cut to 2017.

Muthukrishnan Jeevanantham, a Dalit student of JNU, committed suicide. Days before that he wrote this Facebook post: “There is no equality in MPhil/PhD admission, there is no equality in viva voce, there is only denial of equality…” Payal Salim Tadvi belonged to a Scheduled Tribe. She was possibly the first from her village in Maharashtra to get admission to a medical college. Later, she joined the B.Y.L. Nair Charitable Hospital in Mumbai. In 2019, she committed suicide after being allegedly harassed by some colleagues on caste grounds. 1992. Chuni Kotal of Bengal’s West Midnapore committed suicide. She too was harassed for years. Kotal was the first woman graduate among the Lodha Shabars. May 2022. A village strongman in Uttar Pradesh threatens Dalits with shoe beatings and a hefty fine if they are seen around a farm or a tubewell.

Jashuva wrote Gabbilam in Sanskritised Telugu, thus playing out his literary genius as well as his politics. Jangam, however, draws attention to the fact that Jashuva never attended caste meetings, did not align with any political party.

There is a burning anger in Gabbilam, a stubborn resolve to fling in the face of a pan-India passiveness Dalit issues — hunger, poverty, untouchability. Jashuva is unsparing when he writes in Part II: “A son of our soil mesmerised everyone with his speech.../At the World Parliament of Religions/And Gandhi gained us independence/My fellow Telugu occupied the seat of a professorship at a Western university/ The world applauded our Bengali poet… But they never counted me as one of them.”

But there is also a serenity and generosity of spirit. The Dalit voice tells the bat after she returns from Kailasa: “For the sake of your beloved brothers/With courage, you face God himself directly/It is a kind gesture…”

Jangam says, “I took more than a decade to translate. As a Dalit, when I started reading it, I was able to see lived experiences and the historical injustice faced by Dalits. My endeavour is to bring that historical experience into the mainstream.”