On a floating banana leaf in a pristine forest of lush greens and pointillist treetops stands a frail girl in a diaphanous white frock while a woman fans her with another leaf the way deities are honoured. In another painting, she’s on a lotus pad that’s cupped to echo Botticelli’s giant shell in The Birth of Venus, as a golden effulgence shimmers behind her: a would-be Venus of rural Bengal, descending from above, imbued with divine innocence, no photogenic poses. Sari-clad angels fly around her, accompanied by egrets in a landscape of blended greens under a night sky.

The lotus, the banana leaf and the egrets proclaim the regional identity of the two large acrylic and tempera canvases as clearly as they do the values and vision of the Bangladeshi artist, Rokeya Sultana: a deep, protective concern for the girl child and the resilient woman she must grow into. This merges with, what seems to be, a pantheistic embrace of the environment, as each becomes a symbol of the other in Return the Innocent Earth 1 and 2. Her solo show at ICCR, which had brought together a selection of her paintings and prints done over 40 years, made one wonder why this Kala Bhavanatrained artist wasn’t already a known name in West Bengal.

Sultana pays tribute to the heroic resilience of the ordinary woman as Madonna, alert to lurking perils if she is Lost in the Maze of Hatirjheel, a 54”x108” acrylic in bleeding reds, or when she is hanging from the grab-bar of a crowded bus, eyes watching over her daughter in Madonna and the Passengers, an etching of dense articulation that recalls Somnath Hore. In her everyday chores, the woman is often the dumb, sacrificial goat, decapitated head nestling in her lap, as in an untitled painting.

The horrors of the 1971 struggle remain an incendiary point of reference for Bangladesh, memorialised by the artist in several works. The monochrome litho, Women of War (2017), with its huddle of disrobed women, heads buried between their knees, seethes with the angry tone of J’accuse in an indictment not just of an invading army but also of the addictive game of thrones men play, with women — and the environment — treated as casual collateral damage, both brutalised to crush the defender’s morale and scorch vital resources.

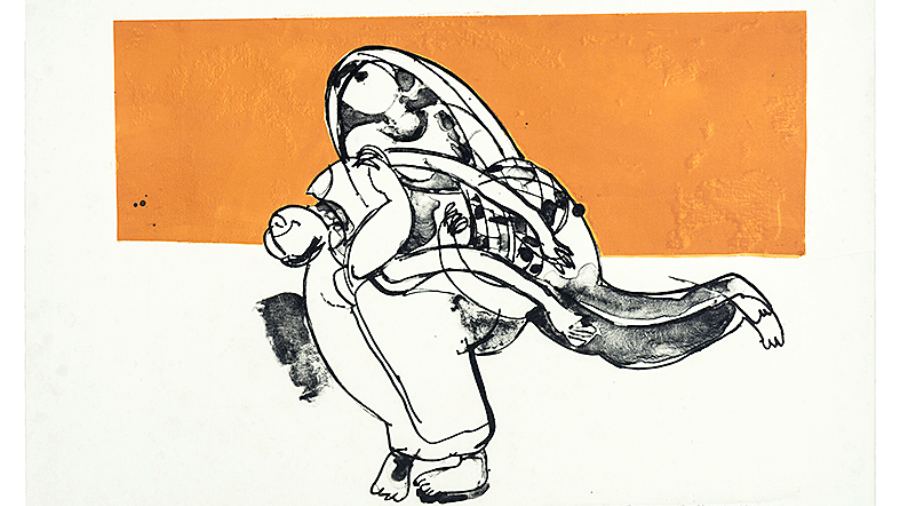

Sultana’s innocuously titled The Mother’s Pouch (2016) takes on an epic scale, not so much because of its size — 64.9”x132.2” (approximately) — but because it weaves in a minefield of details, each a fraught signifier, to distil into a single image the catastrophe of a people forging a nation through fire: the meek homemaker in loose bedroom flipflops and dishevelled sari carries a rifle, ready to kill; the girl with her clutches a bundle; a shadowy line of bedraggled villagers — possibly done in print and replicated to suggest anonymous multitudes — flees from army tanks seen in the far distance, even as the guns of resistance are held aloft in the other corner. But war is gender-neutral in crucifying unknown fighters. And Sultana’s litho, Mother and the Martyred Child (2017, picture) — whose gender isn’t stated — refers, in abbreviated terms, to Pieta as a timeless, universal metaphor for fortitude in ineffable grief.

The figurative tradition of Santiniketan is apparent in the artist’s early prints like Returning Home (1983), reminiscent of the Santhal Family. Simultaneously, she was also experimenting with abstractions of pulsating dynamism and, later, did semi-abstract paintings like Harvesting (1915) with a play of colours. But a blend of nebulous, evanescent tones is best seen in Earth, Water, Air (1999). It’s a tempera that sees Nature as feminine and, hence, vulnerable.