Following in the tradition of studio photography started by pioneers like Samuel Bourne and Lala Deen Dayal, Suresh Punjabi was a visionary entrepreneur-artist. When he stood before his sitters, Punjabi donned the mantle of the archivist of the Great Indian Dream. The Business of Dreams, curated by Nathaniel Gaskell and Varun Nayar at the Museum of Art and Photography recently, put together a show that reveals the presence of a humane vision behind the mechanical eye of the camera. Even in generic mug shots of individuals — taken for the purpose of identification papers and bureaucratic documents, where the subject is usually leached of all character and presented sans expression for the unfeeling scrutiny of the State — the drama of the human face is palpable. So a man in a turban stares back at the camera, his pupils dilated, like the proverbial rabbit caught in the headlights of the State.

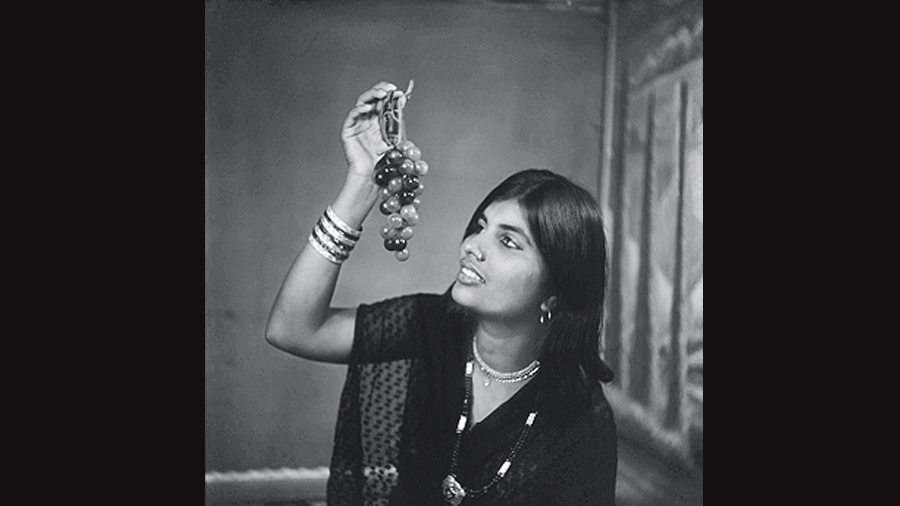

An element of premeditation — whether in striking the right pose or embellishing the setting with suitable props — is obvious in another group of images, featuring individuals or small groups of friends and family members. A woman dangles a bunch of grapes before her mouth, recreating the cliché of a lascivious heroine from the annals of Indian cinema. A man poses stiffly in tie and a pair of bell-bottoms, his hair neatly combed. The influence of cinema shines through these photographs. Punjabi was instrumental in transforming the mundane into a make believe film studio — he would keep film magazines for his clients to refer to if they came around with the express purpose

of emulating the aura of film stars. There were furniture and backdrop to serve as the right prop for a specific mood.

While each of these images stands boldly on its own — carrying its individual aura of distinction and enveloped by its unspoken narratorial arc — together they exist within an ecosystem of emotions that shaped a nation during a certain phase of its development. With their thoughtful curation and textual notes, Gaskell and Nayar draw our attention to details that would otherwise have escaped the untrained eye. For instance, the telephone, embodied in the form of a bakelite receiver, is a recurring presence. A relative novelty in the 1980s, certainly in a small town where Punjabi’s studio was situated, it was a symbol of status, class and modernity for many.