Using the basics of embroidery, Vinoja Tharmalingam maps the terrain where she and her family, and countless Tamils like them fell victim to the waves of violence that have rocked the island of Sri Lanka ever since it gained independence in 1948. The civil war and the anti-Tamil pogroms scarred the land and the psyche of those who suffered unspeakable atrocities for years. Nothing was spared — homes, schools, hospitals. As the title of this exhibition, Anatomy of Remembrances (January 21-March 31 at Experimenter, Hindustan Road), indicates, the young artist scrutinises her memories and those of her fellow sufferers as the raw wounds have dried up and turned into indelible cicatrices. The exhibition has been curated by Natasha Ginwala.

Vinoja was born in Kilinochchi, Sri Lanka, and now teaches art. As an activist, she is determined to bring to light the untold horrors that seared her peoples’ lives, leaving many of them permanently disabled since the land was heavily mined, a threat that still imperils their lives. As in the poem, “Chemmani”, lines from which are inscribed on the gallery wall, “The wind returns to the street/ teeming with life and death...”

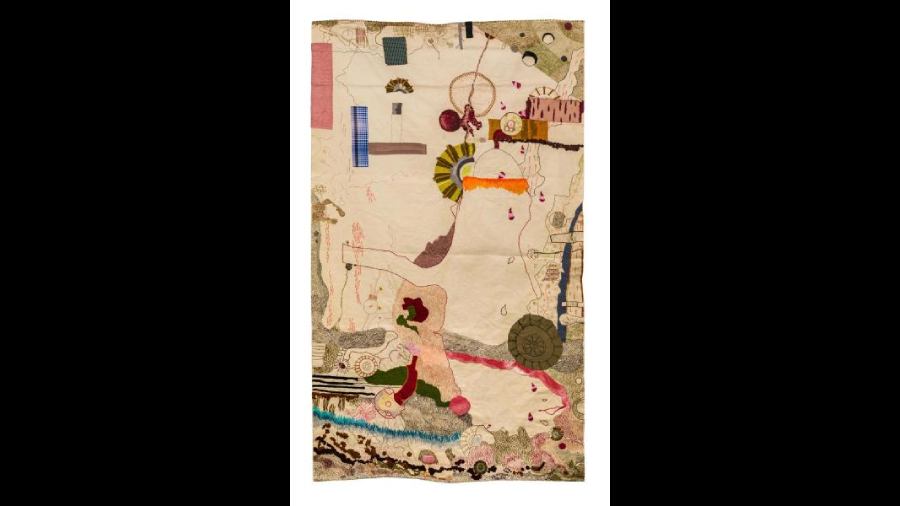

Vinoja is not literally documenting the scenes of the carnage. The killing fields of Sri Lanka are transformed in the artist’s imagination into maps of the region, created with a rough-and-ready kind of cartography. One needs to scan these works carefully to discover indicators of the battles that had once broken out there. The ground is pitted with thousands of running stitches, indicating the lay of the land. She creates bird’s eye views of coastal regions and jungles using dots, knots, lines, burns and textile snippets to indicate vast stretches of land and their beleaguered inhabitants.

Ginwala writes in her curatorial note: “Vinoja invites an immersion within [these] dense landscapes that map historic injustices: a call ‘against forgetting’ and the creative insistence to chart a path toward non-violent living.”

Bunkers are ever-present in her works. Not the kind of bunkers one has seen in World War I films, but ones hastily put together by stuffing sand into clothes and saris sewn together. Her father made bunkers using earth and palmyra foliage, while her mother cooked, always on the alert for signs of danger. Instead of literal truths she opts for markers that could stand for anything from women’s grief to a “well of lamentation and arrested memory.”

In her installation, she creates a curtain of gauze rolls soaked in blood, as it were, dotted with landmines and marked with borderlines.

Studying Vinoja’s work, one realises that even artists who rose from similar circumstances — uprooted from home as a consequence of sectarian violence and ethnic cleansing for decades — may not respond to trauma in a similar manner. Ganesh Haloi had left with his family their home in former East Pakistan to escape a genocide. Like any other refugee, he lived a nightmare as he moved from one refugee camp to another. Yet, there is no indication of pain and misery in Haloi’s paintings of tranquillity as he reimagines life amidst the lush green fields and stretches of water in his former homeland. Vinoja, in striking contrast, gives voice to her anguish as a refugee.