Uday Shankar’s Kalpana is a “dance-film”, but V. Shantaram’s Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje is not. Neither, one guesses, is Sargam, or West Side Story, or Saturday Night Fever, or even Black Swan

“Dance-film” is a new name given to a class of films evolving as a contemporary genre, self-conscious, intelligent and challenging. An old film may qualify occasionally. “A dance-film is one way of describing a film that is also known as screen-dance, video-dance, dance-on-camera or cine-dance,” says Ashavari Majumdar, who is a dancer herself. “It is a film where dance is the language of storytelling,” she adds. The hyphen is important: it signifies the connection between dance and film, and the genre moves fluidly between the two.

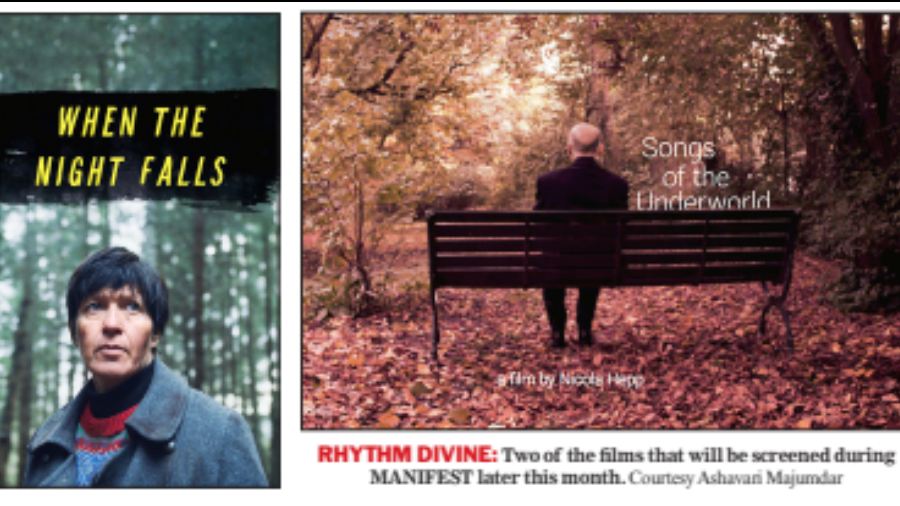

Ashavari is the force behind MANIFEST, a dance-film festival to be held in Pondicherry at the end of this month. This is the first dance-film festival to be held in India. It will be an on-ground event and about 40 films from different countries will be screened. On one of the days, the screening will be held in Auroville as Ashavari, originally from Calcutta, lives nearby now and would like to share the festival with Aurovillians. The venue is a state-of-theart intimate auditorium in the middle of a forest, she says.

Ashavari is organising MANIFEST on behalf of AuroApaar and is the director of the festival. She and her partner Abhyuday Khaitan, a filmmaker who is also from Calcutta, are co-founders of AuroApaar.

The festival will open with a screening of Kalpana, which Ashavari regards as “India’s first and at present only full-length dance-film”.

So why is Kalpana a dancefilm, but not Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje? Though one may feel this is a matter of interpretation, the use of dance as language in a film is quite clear in the emerging genre, she feels. “Uday Shankar was a visionary. Kalpana was made in 1948 and is the prototype for films like Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje,” she says. “There is a deeper and more intense reflection on the relationship between film and dance.” Typically there is very little or no dialogue in a dance-film.

The bond between film and dance is old. “Dancers were the first performers in cinema, in Europe or in Asia. Dance training was often mandatory for actors since the body was the major medium of narration — especially in films of the silent era,” says Ashavari. “Dance has a strong presence in the non-realist cinematic tradition of India, though it is not required in realist cinema.”

In mainstream cinema, dance was made to serve the interest of film. In a dance-film, the dance is not a means to an end in a plot, for romance, or for winning a contest, or even achieving high tragedy through self-annihilation, as is often the case in the very best films featuring dance. “Black Swan, for instance, is about a dancer but not a dance-film. The focus or medium is not dance. Dance is incidental,” says Ashavari.

A feature-length dance-film received by the festival is based on an Agatha Christie mystery with no dialogue and tells the story through dance.

Ashavari is an accomplished Kathak dancer, having trained under Birju Maharaj. She gave up a fully-funded PhD programme at Emory University in the US for dance. A few years ago, with her performance Surpanakha, she looked at the demoness, Ravana’s sister whose nose was cut off by Lakshmana, in a new light and also experimented boldly with the classical Kathak form.

Organising an on-ground, international festival with films from a niche and demanding genre that has no “market” and that too, during a pandemic, is another bold experiment. But Ashavari felt compelled.

“Dance-films (and dance-film festivals) have been around for a while. But it was only during the pandemic that it became a truly global phenomenon,” she points out. The lack of an actual stage or space led different arts to turn in different directions. Many dancers turned to film. It was a new articulation of dance.

Dance-films are not very visible, not online, not in India. “These are artworks not intended for platforms like YouTube. We think of this festival also as a platform for films as artwork. There are festivals for films as documentation, for example, but few for films as art,” says Ashavari.

She continues, “The MANIFEST Dance-Film Festival is the only space in India where you can view contemporary international dance-films.” Most films to be shown are very new.

A stand-out film, Ashavari says, is the Korean film PinDrop. It is about a contemporary problem — of people being together without really being together because of their phones. “It is about the narcissism and exhibitionism of selfies and how the phone disrupts social situations. There are no dialogues.” The filmmaker will be in Pondicherry. Another film to watch out for is Weight of Sugar, which is about slavery and colonialism.

Dance is really about life, and not just about beauty and seduction, and so is film. And there is life outside OTT platforms.

The festival will also organise an “incubator” of dance-film projects that focus on Indian forms. Short dance-film ideas from applicants have been selected and are being developed into dance-films.

At the festival, the organisers are expecting a fit audience, if few.