Not always, but at times you are hurt, and what hurts you is not called anything, because what is being done to you remains invisible. In another place it would be called old-world racism, but in Calcutta that word is not used much, as if it happens in Minneapolis, not here.

One wonders how it affects a bright young person who comes to the city with a dream.

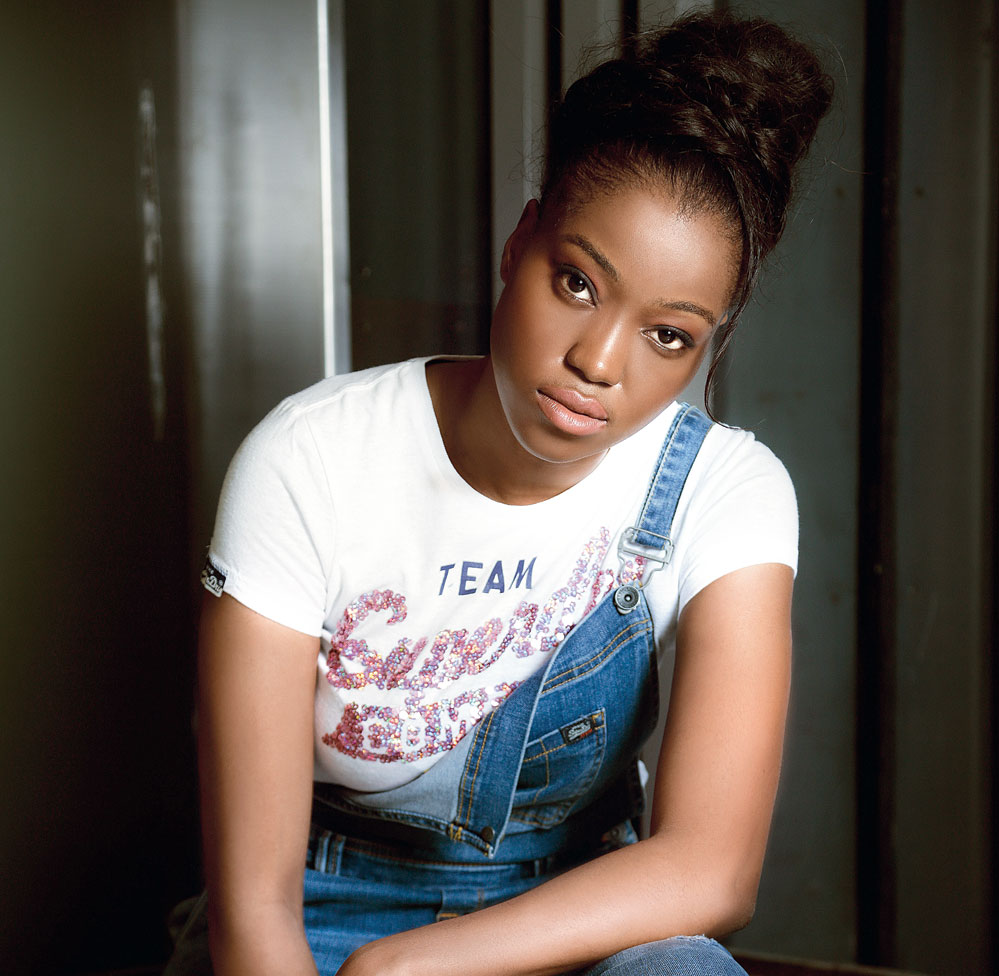

Felicity Dindiwe was 20 when she came to Calcutta seven years ago from Lusaka, the Zambian capital, on a scholarship to study economics at Jadavpur University. She is an attractive young woman — she got a few modelling assignments in the city — and very precise. She seems to remember everything about her stay here with great clarity, including dates. “I came on July 8, 2013, and left on September 28, 2018,” says Felicity, now 27, speaking from Lusaka. She is now helping her father to manage his mining company, which deals in coal and amethysts, and is very busy.

Zambia is not in lockdown because of Covid and the situation is not very bad.

Did her five years in the city include bad experiences because of the colour of her skin?

Not always, but sometimes, yes, she says. She does not speak with rancour. It is not easy to categorise experience in any case. But her very first interaction with the city was a shock. “The taxi driver charged Rs 1,000 from the airport to Jadavpur,” she says.

“It’s not fair, is it, just because we are foreigners?” But that was discrimination at its mildest, cheating actually, and the city tends to fleece all foreigners equally, Black or White, even if it treats them differently. She would face other things.

Felicity did not want to stay at the university hostel at first. Thus began the house-hunt. “It was hectic.” She was on a scholarship, on a shoe-string budget, and struggling under the pressure of her economics honours course. “I had a lot to catch up with,” she says. She had chosen to study here as she felt that Indian education had a higher standard than the Zambian.

Landlords did not turn her down because she was African, she feels, “though others I knew were”. In the five years she lived in four south Calcutta apartments.

At one of the flats she rented, the landlady did not mind her. But there would be trouble if her African friends, girls who were studying engineering in Durgapur, came over for the weekend. “Then she would demand that they pay extra for the water and the electricity,” says Felicity. The landlady would feel that somehow the flat would suffer with the girls around. “But we were neat people. We weren’t messy!” says Felicity.

It was as if a question always hung in the air about their moral character, irrespective of their behaviour, as it often does for people from the North-East. As long as Felicity brought no one in, it was fine. The moment that happened, it disturbed the equilibrium. “The landlady was trying to treat us like children.” Other African students, men from Tanzania and Namibia, who had rented flats in the same house, left.

“In fact we are never asked which country in Africa we are from,” says Felicity.

At the end of her first three years, she decided to move into the university hostel after all. Where food was a bit of a problem, as her palate was not used to the spices of Bengali cooking. But that would not change. Felicity managed. She basically stayed in her room. “There was also the language barrier.”

She remembers with gratitude the effort some of her teachers at the economics department made to help her with her studies. She is also in touch with her former classmates.

Local markets could be terrible. “At the vegetable and meat shops, some would refuse to sell us their stuff,” says Felicity. And festive days could be humiliating: they could feel like true outsiders.

“During the Durga Puja, my friends and I did not want to come back early in the evenings, as there was always a deadline. So we wanted to book a hotel for the night,” says Felicity. Most hotels told them that they would not accept Africans as guests, just as they do not accept couples who are not married.

“But we were treated well in restaurants. And we used to often go to South City mall for its AC,” says Felicity. She got spotted at the mall for modelling. She featured in the ad campaigns of a few brands, including Super Dry (in picture). She also got film offers.

The glamour world did not make her feel unwelcome at all. She attended events and went to parties, and enjoyed herself. The film roles she was offered did not make her feel uncomfortable in any way. Ironically, here she was not made to feel excessively sexual, which is another stereotype of the African woman.

She felt more unsafe in the Metro. “My friend and I were in the Metro. A man touched her bottom. There were so many other women. Why did the man have to choose her?” she asks.

But she speaks calmly, and never mentions the R-word herself in the context of Calcutta. About George Floyd’s death, though, she says that it was even more tragic because he belonged to the country, the US.

And on the whole, India was amazing, she says. She would have even liked to stay on and work in Delhi. But she did not get a job that she had wanted.

She wants to be an entrepreneur as well as hold a corporate job. And now she has to run, because there’s too much work!