Sept. 26: Ratan Tata has finally shown the power of the seemingly innocuous preference share - and this could be an object lesson for corporate chieftains looking for ways to build an impregnable defence against attacks from disgruntled minority shareholders.

The Tata patriarch started issuing preference shares at the 100-year-old Tata Sons, the holding company of the $103-billion Tata group, sometime in 2009.

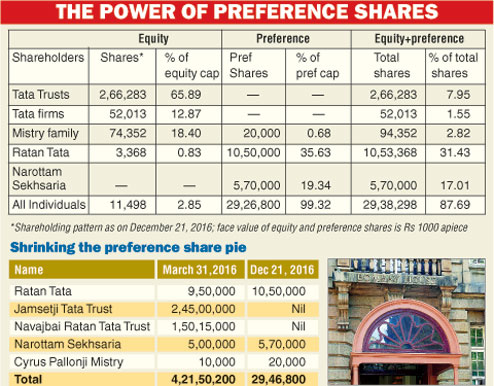

By March 2016, the total number of preference shares issued had swelled to more than 4.21 crore with the two Tata trusts - Jamsetji Tata Trust and Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust - holding the bulk of the shares issued at 3.95 crore.

This fairly large mountain of preference shares was dramatically whittled by December last year, shrinking by almost 94 per cent to a little over 29.46 lakh following massive redemptions even as the battle with the Shapoorji Pallonji family escalated in late October that eventually saw Cyrus Mistry step down as chairman of the Tata group.

In fact, Tata Sons issued 311,600 preference shares in October 2016. Of this, Ratan Tata got 1 lakh shares.

The preference share has the characteristics of debt and carries a pre-specified dividend rate that must be paid before any dividend is paid to the holders of ordinary shares. Unlike ordinary shares, the preference share is a non-voting stock and, therefore, evokes ambivalent reactions on its usefulness.

But it can complicate matters for a certain class of shareholders especially when they try to work up the courage to take on company managements.

In fact, the dramatic recast in the preference share base at Tata Sons has had a huge bearing on the case of oppression and mismanagement that Cyrus Mistry has brought against Tata Sons under sections 241 to 244 of the Companies Act of 2013.

Last week, Justice S.J. Mukhopadhaya of the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) handed down a verdict which made one thing very clear: minority equity shareholders who wish to bring charges of oppression and mismanagement against the people who run the show in the companies in which they have an interest will need to keep a close watch on the quantum of preference shares that the company has issued.

In his verdict, Justice Mukhopadhaya said the definition of "issued share capital" in section 244 of the Companies Act 2013 (which determines who is eligible to file a charge of oppression against an existing management) is equity share capital plus preference share issued.

The definition of issued share capital has been a hotly disputed issue in the case that Cyrus Investments Pvt Ltd and Sterling Investment Corporation Pvt Ltd - the two Shapoorji Pallonji family investment companies - filed against Tata Sons last December. The two entities together hold 18.4 per cent of the equity share capital in Tata Sons.

The Mistry case represents the first test of the eligibility criteria spelt out in section 244 of the Companies Act 2013 for filing a charge of oppression against an existing management.

Under section 244, a case of oppression and mismanagement can be filed only if the litigant falls into one of three categories: (a) not less than 100 members of the company; (b) not less than one-tenth of the total number of members; or (c) any member or members holding not less than one-tenth of the issued share capital of the company.

In the Mistry case, the first two categories were irrelevant since Tata Sons has only 28 equity shareholders, including Cyrus Investments and Sterling Investment Corporation. This goes up to 51 if you include the preference shareholders.

In the past, several courts have ruled that issued share capital means equity plus preference share capital and only entities holding 10 per cent of the combined share capital can file a charge of oppression and mismanagement. But all those were cases filed under the Companies Act 1956.

Justice Mukhopadhaya's ruling means that the eligibility bar for such cases will continue to be set high for disgruntled minority shareholders, ensuring that the courts are not flooded by "frivolous" cases against existing managements.

Minority shareholders who were expecting the new law to provide greater protection against autocratic decisions of company boards of directors will find their hopes dashed after the NCLAT verdict.

Legal absurdity

C.A. Sundaram, counsel for the Mistry firms, had tried to argue that the Companies Act 2013 had made a significant departure from the earlier act by creating and recognising different class of members in a company.

Consequently, the term "issued share capital" in section 244 could only refer to the relevant share capital - in this case equity shareholders - "otherwise it would lead to an absurdity that holder of shares who are completely disinterested in an action, or even have a conflicting interest to a petitioner qua such action, would necessarily have to join in with the aggrieved party and their percentage of shareholding would also be taken into account for the resolution of such a dispute".

Sundaram also argued that if issued share capital was interpreted as equity shareholding plus preference share capital it would lead to an absurd situation where even the Tata Trusts - which hold 66 per cent of the equity capital - would not be able to file a suit of oppression based on their equity holding.

Given the existing share capital structure, only someone commanding 81 per cent of Tata Sons' equity share capital could bring such a suit, which he characterised as a legal absurdity.

Justice Mukhopadhaya stated this even more baldly: "We find that except Ratan Naval Tata having an issued shareholding of 31.43 per cent and Narotam S. Sekhsaria (chairman of ACC and the founder of the Ambuja Cement group) having 17.01 per cent shareholding capital of the company, none of the 49 members are eligible to file an application under Section 241, individually having less than 10 per cent of the shareholding."

This situation would not have arisen if the two Tata Trusts had not redeemed their 3.95 crore worth of preference shares.

That means that Ratan Tata, who holds only 3,638 equity shares (roughly 0.83 per cent of the equity capital), has wrested effective control over Tata Sons through his 10.5 lakh preference shares.

The Cyrus Mistry camp has been crowing about the victory it won when Justice Mukhopadhya waived the minimum minority shareholding rule to allow it to pursue the case against Tata Sons in before the company law tribunal.

But two factors will make things rough for the Mistry petition: first, the company law tribunal has already ruled against the Cyrus camp in its April verdict when it held that it didn't meet the eligibility criteria to file the suit. It also found no merit in the charge of mismanagement against Tata Sons.

Second, on the very day that the NCLAT gave its verdict, the Tata Sons board altered its articles of association by turning into a private limited company which will stymie the Mistry from selling its shares to any outsider.

It also received shareholders' approval to confer voting rights on the preference shares if the Tata holding company fails to pay a dividend for two consecutive years.

This really is game, set and match for Ratan Tata - and all because he has shrewdly used his preference shares as a weapon to bludgeon the Mistry claims.