Book: The End of the Chinese Century? How Xi Jinping Lost the Belt and Road Initiative

Author: Bertil Lintner

Published by: HarperCollins

Price: Rs 499

When China’s economy surpassed that of the United States of America in size in 2014 in purchasing power parity terms, the Nobel laureate and economist, Joseph Stiglitz, declared that it was time for the world to acknowledge the ascension of a new boss: The “Chinese Century”, he said, had arrived. “When the history of 2014 is written, it will take note of a large fact that has received little attention: 2014 was the last year in which the United States could claim to be the world’s largest economic power”, wrote Stiglitz. “China enters 2015 in the top position, where it will likely remain for a very long time, if not forever. In doing so, it returns to the position it held through most of human history.”

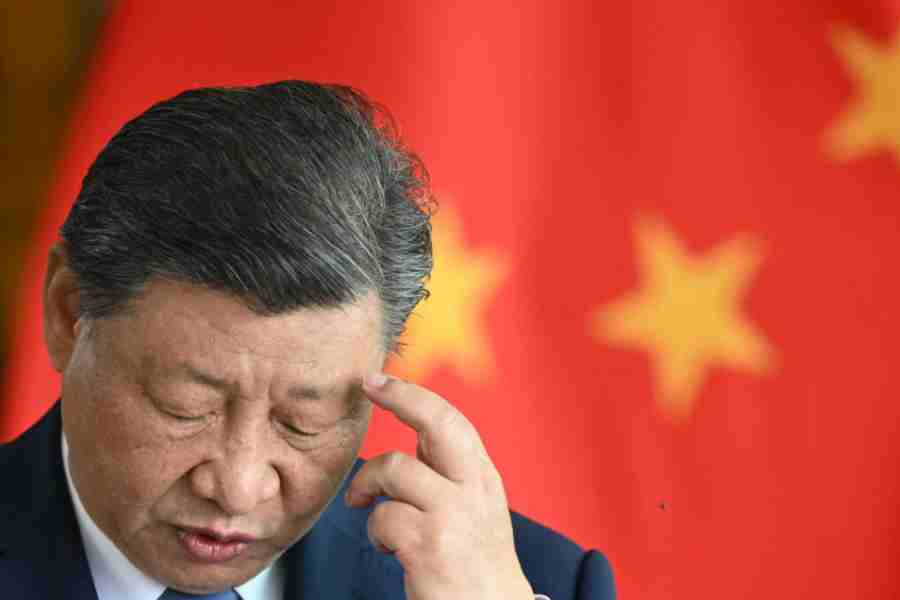

A decade later, with the world in 2025, the veteran Swedish journalist and author, Bertil Lintner, wants to call time on Stiglitz’s prophecy — one that, to be fair to the Columbia University professor, was echoed by many geopolitical analysts in the first two decades of this century. Blunt as always, Lintner sums up the thrust of his argument in the title of his latest book, “The End of the Chinese Century?”. Starting with the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative by the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, in 2013 — a network of highways, ports and railroads to connect Asia to Africa and Europe — Lintner ends with the conclusion that the communist leader now faces deep struggles within and outside his country.

The result, according to Lintner: The Chinese Century is over before it truly began.

A long-time analyst and observer of China and its relations with its neighbourhood in particular, Lintner in his book offers sharp insights into Beijing’s challenges today. These obstacles to China’s rise are indisputable and many — from a no-holds-barred rivalry with the US, to failed promises linked to the BRI, to the difficulties posed to its ambitions by conflicts like the Russia-Ukraine war. Indeed, it is today far from guaranteed that China will displace the US as the world’s pre-eminent superpower.

Lintner smartly points to what he describes as “empty monuments of Beijing’s insatiable desire for growth”. From empty mansions in China taken over by cattle grazers to a railroad in Kenya that leads to nowhere; from a port in Sri Lanka to an airport in Nepal that both see little traffic, the book reveals the gulf between China’s ambitions and their impact on the ground.

Yet, while touching upon multiple factors that have contributed to China’s recent stumbles, the book never really dives deep into exploring why Beijing has failed — so far, at least — to deliver on the promise that Stiglitz referenced a decade ago. Where has China fundamentally gone wrong? Were its dreams of world leadership always destined to fail? Could it have done anything differently over the past decade?

Lintner also misses a beat in not delving into the similarities and the differences between the British Century (the 19th), the American Century (the 20th), and China’s stunning rise over the first quarter of the 21st century. The role of British colonialism and that of the World Wars are left unaddressed. America in the 20th century never faced the kind of challenges from Britain that can compare to the almost existential fight for supremacy that China and the US are locked in, across economics, technology, geopolitics and more. Indeed, Washington and London were allies through much of the US’s rise. Without this context, it is difficult to understand the concept of a Chinese Century and whether it really could ever have been expected to look like the dominance that Britain once enjoyed, and the US still does.

Where the book scores is in its detailing of how China’s relations with its neighbours have evolved over the years — and how that history shapes those ties today. Lintner uses hard evidence to call bluff on some of the exaggerations of Chinese influence beyond its borders in previous centuries, including through the Silk Road. He argues that China might downscale its ambitions to focus more on its immediate region, drawing lessons from the roadblocks it has encountered in the past decade. If that does turn out to be the case, then Lintner’s book could prove to be a particularly invaluable contribution to understanding what the future might hold for the Chinese dream.