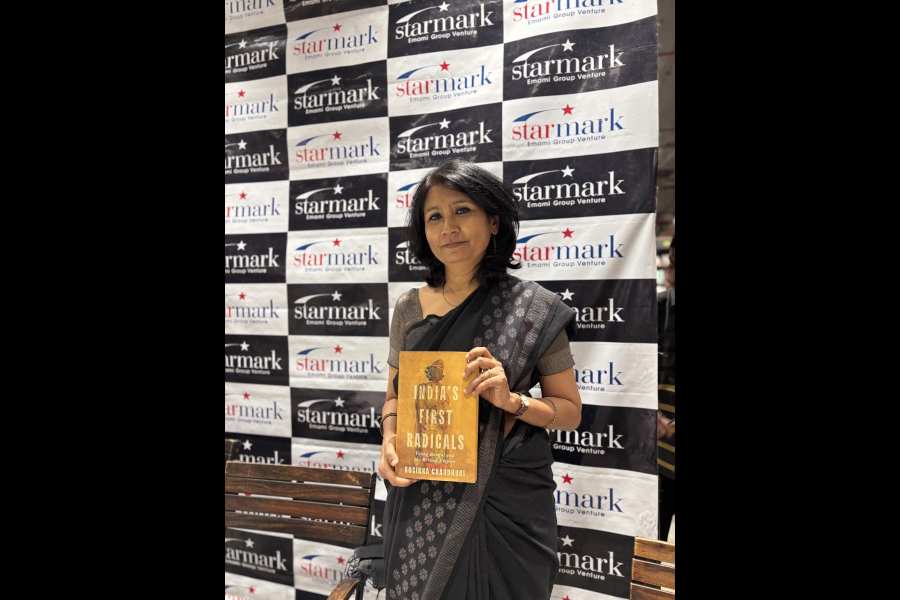

Author Rosinka Chaudhuri’s new book, India’s First Radicals: Young Bengal and the British Empire, on the young radicals of Bengal of the mid-19th Century, appears at a perfect historical moment when protests against global injustice are growing louder. I spoke to the author about a range of issues the book explores and the new ground it treads.

The 19th Century was a long and explosive one, with young people awakening across the world against colonial rule and the shortcomings of their own Asian orthodox societies. Close on the heels of the Young Bengal radicals came a string of young reformers in China and Vietnam who demanded modernisation, self-strengthening, and internal reforms.

Against this background, I asked Ananda Lal, publisher and former professor of English at Jadavpur University, what makes Rosinka’s book stand out in the context of the literature already available in this time period. What is “new” about this study? Lal said, “No scholar has focused specifically on this movement in such voluminous (400 page) detail,” explaining that much of the material Rosinka has marshalled into a narrative has not been used so far because of inaccessibility to the archives, and the deterioration of Calcutta libraries. In contrast, the British Library in London has preserved most of it. And how relevant is the book? Lal adds, “We are all the intellectual children of Young Bengal. There is a direct descent from their principles of dissent and protest against majoritarian obscurantism to our fights for the same general causes today.”

Excerpts from the interview with Rosinka about India’s First Radicals, published by Penguin-Viking:

What was it about the First Radicals group of Bengal that made you so acutely interested in the philosophy, activism, and lives of this young group of highly intelligent young rebels?

In 2008, I published Derozio, Poet of India: The Definitive Edition from material collected at the British Library over a period of a fellowship at Cambridge University. I had, at the time, also found very interesting reports on the students of Derozio at the Hindu College — their political positions, social rebellion, and acutely intelligent responses to their situation at a nebulous and formative moment for Indian modernity — that I could not include in the volume. I suppose I had also always been fascinated by the fact that they had somehow managed to attract both the highest regard and the most scathing criticism from commentators. It seemed both a challenging and rewarding proposition to sift through the evidence and tell the story as it had not been told before.

How did history become the focus of your career?

History has never been the focus of my career. I have studied English literature all the way through to my D. Phil at Oxford, yet it intersected with my love of poetry in my work as a cultural historian.

In his voluminous praise of your meticulous research, political scientist and anthropologist Partha Chatterjee said it took you two decades of mining the archives over continents to find the material to write this book. Which were the most helpful repositories that aided you and how did you organise such remarkable information?

Partha-da was director of the CSSSC (Centre for Studies in Social Sciences) when I joined, and is still honorary professor there. He has been a constant interlocutor in all of my work over the years, and I am grateful for his support, always. I have also been fortunate in having been in conversation, via the Centre, with some of the most remarkable thinkers of our times — Gautam Bhadra, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Ranajit Guha, apart from having the support of senior colleagues such as Tapati Guha Thakurta, Manabi Majumdar or Keya Dasgupta. What their conversation and collegiality brought was as essential as mining the archive was to this project — insights gained, perspectives refreshed, and opinions revised over the two decades of retrieving the material and presenting my arguments at some of the most challenging staff seminars there. The material was almost entirely collated from the British Library over the years with scant funding, visiting positions, and a combination of improvisation and persistence. This archive is not available in India, and that is probably one of the reasons the work could not be done before this.

What were the ways you discovered the threads, from one set of documents to another? Could you share one eureka moment where you found something unexpectedly that really got you?

There was no one eureka moment; there never is. Any tales of one eureka moment are probably made up. It was very difficult to find a connecting thread and to organise the vast amount of material I had garnered initially, as Young Bengal seemed to mean anything and everything over the course of the 19th century — anyone who disobeyed dietary and caste restrictions, spoke in English, disrespected Hindu customs, or drank too much seemed to be so labelled. The structure of the book fell into place once I realised that a number of dramatic episodes had occurred in a single year — 1843. Telling the stories of what had happened that year would be possible to range over the period that began in 1831 and came to an end by 1846 or so when the first Indian political party formed by Young Bengal ran out of funding with the death of Dwarkanath Tagore.

When you were working at the libraries in the UK, how many hours of actual reading did you put in? The archive is the historian’s second home, and it can be a very lonely enterprise. What did your breaks look like?

The India Office Library on the third floor of the British Library shuts at 5pm, and readers are encouraged to start packing up a half hour before. As a result, I would switch almost immediately to the Rare Books Section, which is open till 8pm and which has a large room of microfilm readers, which were essential to my work. I would work on average from 10am or 11am to 8pm with breaks for coffee or lunch — the cafeteria there, like everything else, for an Indian in London, is expensive, and I would try and carry my own sandwich and orange juice with me to save money. Time is limited for a scholar from India working there, so there is a sustained effort to get as much done as possible in the time available. I wouldn’t call it lonely, because you don’t want company as such while working.

One of the most difficult decisions might have been to figure out your readership. How did you manage to find such a felicitous balance to hook the reader and persuade them to be beguiled?

Truthfully, I have never thought of a readership while writing a book. If I had, I would have done work that was more oriented to contemporary fashion. As a student with a leading postcolonial theorist and as a supervisor, I could have taken up postcolonial studies and forged ahead; as a woman, I could have opted for gender studies and found a niche; as a politically-minded person I could have chosen a side to belong to and found support in my comrades. I’m sure I would have done better in life if I had, but my temperament is such that it rejects orthodoxies of all kinds, even self-imposed ones. So I wrote the book as I have written all my other books — to say what I wanted to in the way I wanted to — regardless of publisher or reader.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life, and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College