Book name- THE GREATEST GAME

Author- Stephen Alter

Published by- Aleph, Price- Rs 799

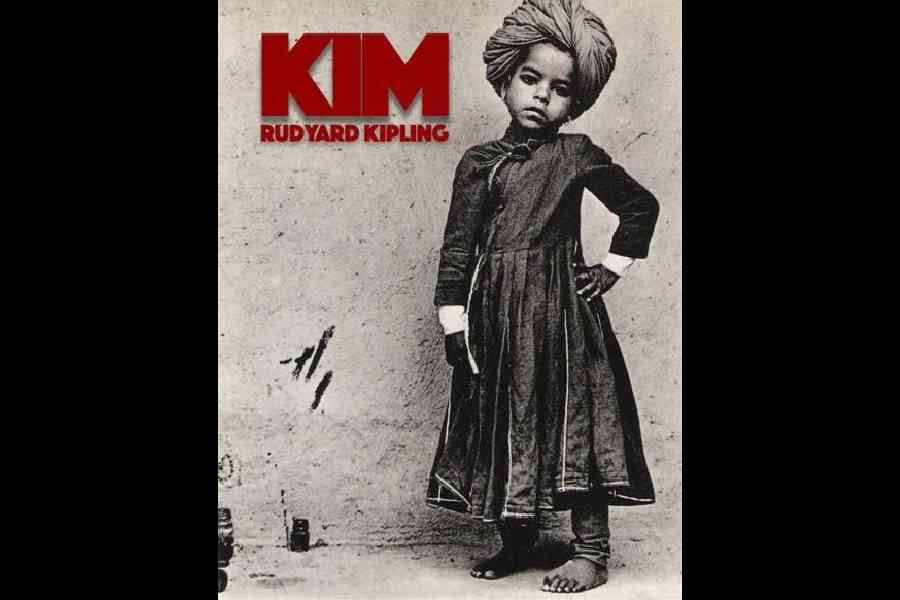

Kim is back — alive and itinerant in March 1947 — even though his name, Lt. Kimball O’Hara, is inscribed on the War Memorial of the Third Anglo-Afghan War on Kingsway, now India Gate, on Rajpath. Witnessing communal frenzy and riots, dodging bullets, and carrying a dishonourable act tucked up his sleeve along with his many loves, Rudyard Kipling’s endearing Kim resurfaces on the pages of Stephen Alter’s book.

Kipling’s Irish orphan of the streets, more Hindustani than White, is now sixty, still hugging his leather amulet with the three papers his father gave him, adept at spinning yarns about his past and moving easily between personalities -- Hindu and Muslim, even that of a White man, a persona he has come to dislike.

Here, Alter casts him in the drama of Indian Independence. Assigned the task of uncovering the conspirators who plan to blow up a railway bridge on the Ravi, Kim discovers a more sinister plot and soon heads to Dilli to foil it. Motor mechanics, courtesans, princesses — he straddles many worlds as both spy and lover.

Kim takes a train in a bid to rescue his courtesan lover, Champa, from communally-charged Lahore to Dilli, using her and her two young apprentices as cover for his mission. The train is attacked. Fear saturates the overstuffed, suffocating compartment. He finds himself face-to-face with the death of an unknown riot victim. Appropriately, Champa tells him how inconsequential he is: “You are not an actor, or a spy, or a thief.” “You’re a nobody, like the rest of us — a faceless castaway who has no home and no identity any more.” As the Lama had told him many years ago, death is a cycle, not an end.

Alter preserves Kim’s free spirit and his search for spiritual solace. Homeless forever, even the semblance of a home he had in Lahore gets vandalised. In a poignant twist, Alter has Kim fake his death to see his name among the martyrs — a homage to the nobodies who shape history without grand titles.

The narrative’s language is suitably adapted (Umballa is now Ambala); Hindi words and even some expletives are retained; and it is a pleasure to stumble upon the names of old Connaught Place stores like Kemp & Co. Despite other pleasures — verses of Ghalib and Mir are served generously — Alter’s rendition of an older, more Indianised, Kim somehow lacks the flavour of Kipling’s original. Descriptions of an India about to be sliced apart do not fully convey the devastation that pre-Partition India must have experienced. The understated portrayal of communal hatred sits uneasily with an Indianised Kim narrating in the first person.

This is a convincing tale, but it lacks the jaadoo of the master raconteur whose path Alter has dared to walk.