BOOK- HIGH ALTITUDE HEROINES: FOUR EARLY EXPLORERS IN THE HIGH HIMALAYAS

AUTHORS- Alexandra David-Néel, Fanny Bullock Workman, Henrietta Sands Merrick and Lilian A. Starr

PUBLISHED BY- Speaking Tiger

PRICE-Rs 599

Mountaineering has generally been perceived as a masculine endeavour; its narratives of heroic feats are dominated by men. High Altitude Heroines successfully challenges this perception by bringing forth the remarkable journeys undertaken by the four pioneering women mountaineers who defied norms and limited opportunities to explore the Himalayas in the early decades of the 20th century. Their first-hand accounts are more than just valuable registers of the local geography; their stream-of-consciousness narrations shed light on their resilience, their instinctive responses to the environment and, more importantly, portray the way of life in the Himalayas during the time.

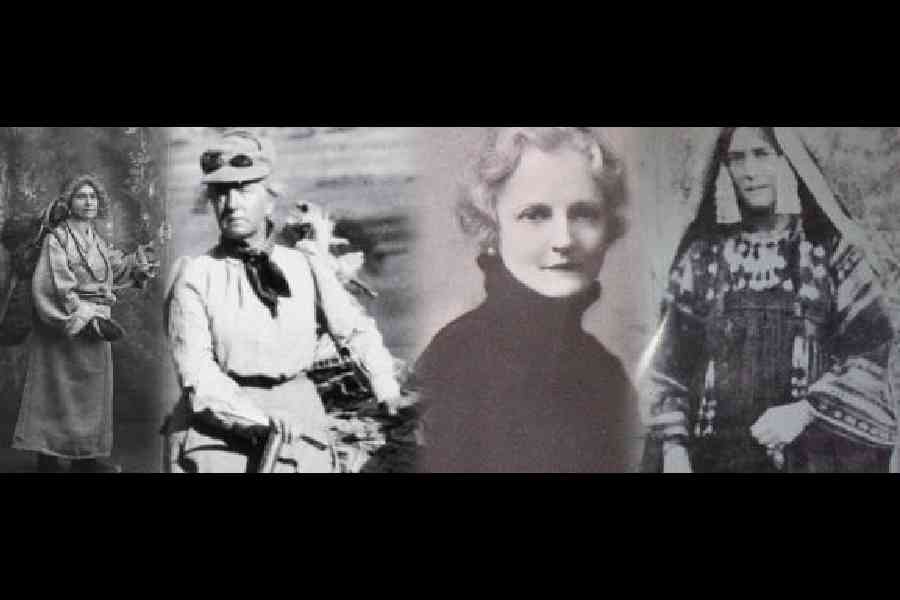

The titular “heroines” — Alexandra David-Néel, Fanny Bullock Workman, Henrietta Sands Merrick and Lilian A. Starr — are not only driven by their thirst for adventure but also by their sheer resolve to break stereotypes. In that sense, they were Eve’s “great-granddaughter[s]”, as highlighted by David-Néel in her account, open to the possibilities that the “wide unknown world” posited. “My Journey to Lhasa”, the account by David-Néel, the first Western woman to reach Lhasa in “Thibet” in 1924, then a “Forbidden Land” to foreigners, is marked by her constant efforts to protect her identity. Disguised as a poor pilgrim, she traverses treacherous paths at night, ends up taking several detours, comes close to encountering four-legged beasts, and even consumes dye from her unwashed hands lest her cover be blown.

Merrick, the second heroine, is an observant mountaineer and her richly detailed record, “In the World’s Attic”, offers a window to Ladakhi customs and history.

In “Peaks and Glaciers of Nun Kun”, Workman, then 47 years old, summits a mountain massif without modern gear, a tale that drips with a heavy dose of thrills, while Starr’s “An Errand of Mercy: Searching for Miss Ellis Among the Afridis” is a poignant tale of determination that entails rescuing a kidnapped girl from the Afridis, a tribal group residing in a fierce frontier.

Their heroic qualities notwithstanding, the women’s survival in these formidable mountains capes would not have been possible without the support of local sherpas who are seldom given credit in these chronicles. For example, much of David-Néel’s assent is marked by the hard labour of her companion, Yongden; his skills as an oracle, even though they save David-Néel from getting exposed, receive a mocking glare from her. This is because the experiences of these women expeditionists were also shaped by the broader arc of imperialism and its legacy of racism. Their Occidental attitudes to the local traditions must thus be viewed through the postcolonial lens. While Merrick describes the Ladakhi population as “ragged, filthy, cheerful”, Starr labels the tribesman as “unsophisticated”.

Even though the explanation of Tibetan words in the footnotes was illuminating, the book would have benefited from photographs of these remarkable women who transcended both physical and societal barriers.