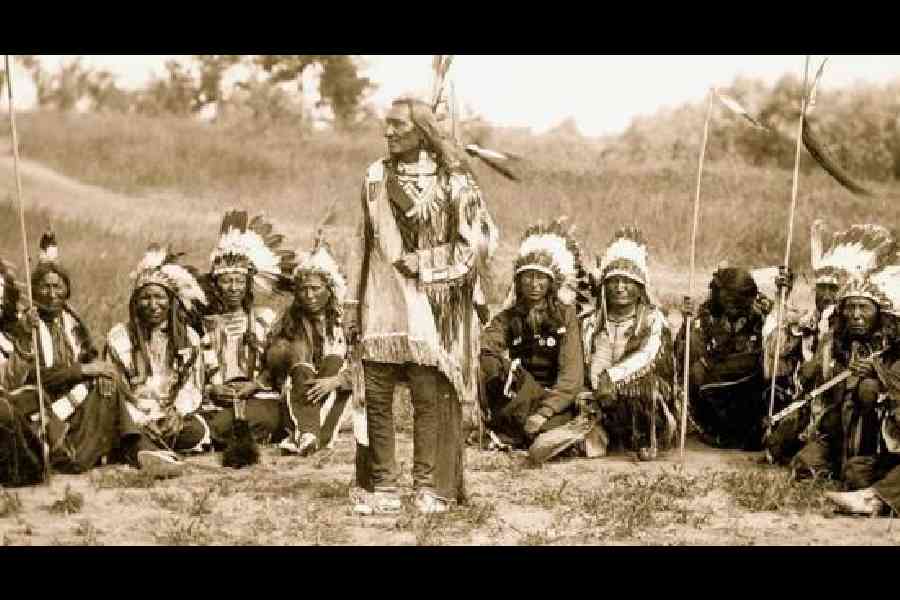

Book name- NATIVE NATIONS: A MILLENNIUM IN NORTH AMERICA

Author- Kathleen DuVal

Published by- Profile, Price- Rs 999

In the inaugural chapter of her book, Kathleen DuVal draws attention to the significant factors that contributed to the rise of flourishing urban spaces even a thousand years back: “Cities arise only when people are able to live apart from the locations of food production — when agriculture allows their lives to no longer be intimately entwined with the labor of growing food.” Comparing early Native North American urbanisation with other cities of the preindustrial world, she insists “we see that these elaborate and cosmopolitan urban civilizations had a great deal in common in their scale and infrastructure.” Much beyond infrastructure, as DuVal unearths, these native nations, in tune with their contemporary world, had established thriving trading networks: “Like the Silk Road or the trans-Saharan routes… North American trade routes stretched from the Great Lakes to the Mississippian city-states in the Southeast and the Midwest to Chaco, in today’s New Mexico, and the Huhugam of Arizona, south to Mexico, and north to Canada.” Their acumen for negotiating trade deals extended much beyond the early centuries, flourishing even with the advent of colonialism. In the fourth chapter, DuVal explores how the Mohawks not only managed to establish commercial associations with the Europeans but also “had the power to control the terms of trade and to draw Europeans into their alliances and wars”. So much so that contrary to common perception, the European powers practically had no control in their dealings with the Mohawks.

Dismissive of the old stereotypical perception of the native people of North America as being primitive, DuVal draws parallels between them and contemporary urban populations from the rest of the world, even including their European counterparts. Vindicating her stance for the inclusion of their history in the various texts of world history, DuVal assiduously explores the last millennium while underscoring the remarkable survival story of the native nations in North America. Drawing attention of her readers to the resilience of these native states, she emphasises in

the Foreword: “Indigenous civilizations did not come

to a halt when a few wandering explorers or hungry settlers arrived in their homelands, even when the strangers came well armed.” Contrary to the dominant historical discourse, Native Nations testifies in detail to the evolution and the continuity of native power in North America down to the present day: “Before and during European colonization, Native North Americans lived in diverse civilizations with complex economies and commercial and diplomatic networks that spanned the continent. They live in history, adapting to changes in the Americas for at least twenty thousand years — and counting.”

Broadly divided into two distinct parts consisting of six chapters each, DuVal’s prodigious research is broadly revisionist by nature as it meticulously rescripts the erstwhile assumptions pertaining to the lifestyle and the existence of the native populations of North America. The first part of this work scrutinises the socio-political dynamics of the various native communities while the section part testifies to their adaptability and endurance as well as their negotiation of the challenges that they were forced to engage with. Based on thorough archival work and oral histories, DuVal illustrates how indigenous people negotiated with such evolving challenges as climate change, journeying from the agricultural prosperity and abundance of the Medieval Warm Period (10th-13th century) to the crisis of the Little Ice Age (circa 1250). While European surveyors and archaeologists had erroneously inferred from the urban ruins (Chaco Canyon and Cahokia) of the Little Ice Age the general breakdown and the tragic catastrophe of the golden age, subsequent oral historical narratives, DuVal asserts, bore evidence to the contrary. As DuVal observes, “At the same time, in the process of de-urbanizing, creating relatively more egalitarian societies, and, in some places in the coming centuries, facing destruction wrought by Europeans, Native people retained both a memory of the past and some of its attributes, from plazas (now as smaller town squares) to sacred iconography.” This nascent period also saw the advent of more equitable governance, with negotiated peace and intricate economies being dispersed across the whole of North America. When the Europeans arrived in the sixteenth century, their understanding of the native societies, oblivious to these past developments, was flawed, often contributing to the misrepresentation of these indigenous communities.

DuVal also insists that the Native nations were not always at the receiving end of victimisation. In fact, they frequently entered into truce or engaged in conflict with the colonisers for survival and benefit. “In these early centuries, Native Americans continued to control almost all of North America. When they lost ground, it was almost always to Native enemies, not European ones. And yet historians have long told this story exactly wrong, rushing to backdate late-eighteenth and nineteenth-century Native losses to more than a century earlier.”

DuVal’s outstanding research makes a formidable plea for the integration of indigenous people into global history instead of them being disregarded or projected merely as victims at the hands of the colonisers. She contends that their sovereignty and influential presence not only matter in the present but will continue to shape the future as well.