Book name- THE ELSEWHEREANS: A DOCUMENTARY NOVEL

Author- Jeet Thayil

Published by- Fourth Estate, Price- Rs 699

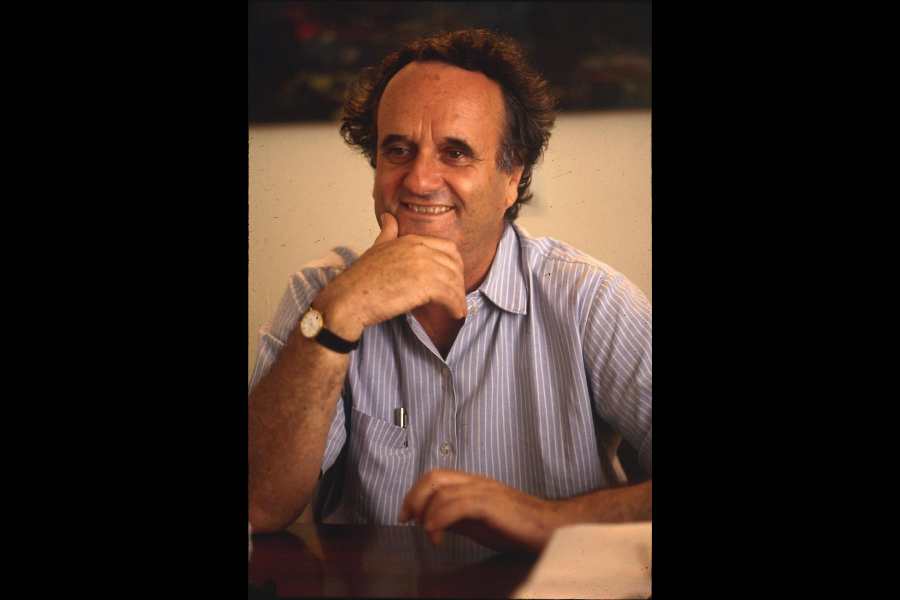

Hearing Jeet Thayil talk in the hushed clamour of a cocktail event, but in the verdant alcoves of Sunder Nursery (in February, when I met him), tells you: mystique and seriousness go a long way. Atop These Errors Are Correct (the winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award), he languishes on a bed beneath round sunglasses. In photographs: effusive if reserved, 40-something yet 64. In The Elsewhereans, he distils his life into a glass with a salt-and-asbestos rim and picks up, with relish and true virtuoso magnificence, a shaker.

The book has been marketed as a “documentary novel”, a term that Barbara Foley studied in Telling the Truth: The Theory and Practice of Documentary Fiction, where she says that the novel is similar to the autobiography because both are narratives, versions of reality. This is the story of Thayil’s life but also not his life (... and not necessarily a version of it…), born to a prolific writer (... not necessarily his own father…) and a schoolteacher (... not necessarily his own mother…); he owes them, in real life as in the book, so much. The book travels to Kerala, Paris, Bombay and Hong Kong, and is broken up by folios of self-mythology and photographs from Thayil’s family. They installed the first bidet in Cochin! I chuckled heartily through a conversation about a song that goes “Sucky […] smells like sushi”. Thayil is also a celebrated poet; his quiet musicality imbues the book so that sentences ring like a regal handbell. It flies by in its refreshing lack of that arid feeling of forced immersion that some bildungsromans have sadly mastered, and captures a postcolonial India in its churches and life preservers and tittle-tattle. What whorl of your mind is Indian? (You were never really here.)

In the The Oxford Handbook of Modern Indian Literatures (which raps Thayil’s knuckles), Ragini Tharoor Srinivasan’s chapter studies Gayathri Prabhu’s experimental memoir, If I had to Tell it Again, and Amit Chaudhuri’s autofictional novella, Friend of My Youth (featuring “Amit Chaudhuri”, a version of the writer (?) (Chaudhuri disagrees)), to argue that the rise of the autofictional tradition in anglophone literature in India marks a break from early postcolonial Indian English literature, which was concerned with “certain familiar forms of engagement with nation and world”.

Thayil is no stranger to this tradition; in The Book of Chocolate Saints, he parodies the oft-scoffed, lengthy opening of his Narcopolis, which (along with Low) borrows from his long-abandoned opium and heroin addiction. He’s convinced Gitanjali is somewhat overrated; in The Book of Chocolate Saints, a character dislikes Yeats’s affection for it. It’s fun. And yet, for all the possible parallels between the decoloniality of narrative and form, only a certain class of authors can do autofiction that piques any interest. It’s a more interesting question than a nobody asking who’ll buy her autobiography. Rachel Cusk’s autofictional trilogy invites attention because of speculation that Cusk, like her protagonist, is a bad, fatphobic, person, “too intellectual” to function. Some of Annie Ernaux’s volumes border on rote memorisation because of the sheer routine of her routine. But it’s all fair. In 2012, a headline in The Times read: “Jeet Thayil: the ex junkie shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize”. In an article in The Caravan, he is described as canoodling in a bathtub in the middle of a party. All of the above, and also that he is really adored among the reading masses of New Delhi and Bombay, cements his persona of a consummate litterateur: misadventurous, acclaimed, loudmouthed, charming; a footballer in business casuals. It’s the known that flavours what is unknown, for repeated flashes of recognition and that sweet release arrived at after years and decades of following a truly gifted author’s astonishing career in the arts. What an extraordinary work.