It was a mistake, the Supreme Court later said. But by then it was too late. Ravji Rao, or Ram Chandra, had been hanged to death. Almost 20 years later, Banwar Lal still finds his eyes welling up when he passes his old school friend's house. Ravji, who was from a tribal community of Rajasthan, was executed on May 4, 1996, for killing five people, including his wife and three minor sons, and attempting to murder his mother and a neighbour's wife in Banswara in Rajasthan.

"Ravji had dreams of becoming a school teacher. His was a happy family and I had never seen him quarrel with anyone, let alone with his wife," Lal says.

In 2009, 13 years after his death, the Supreme Court, in the case of Santosh Kumar Satish Bhusan Bariyar vs State of Maharashtra, declared the Ravji case "per incuriam" - a Latin term used to denote carelessness. The case had failed to follow the Bachan Singh judgement (1980), which stated that circumstances relating to "the crime as well as the criminal" be looked into before pronouncing a death penalty.

"I have heard that the Supreme Court had admitted its mistake. But what is the use now," Lal asks. "The court cannot give back his life."

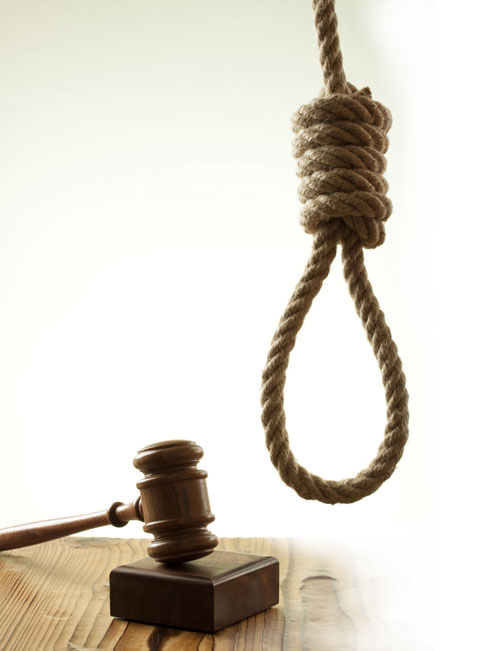

Indeed, once a person is hanged, there is no return. The debate around Yakub Memon's execution earlier this week once again highlights the many cases of people who were hanged, but who should have lived.

The judiciary, after all, consists of human beings. There are errors in passing judgement, there are some judges who are more prone to handing out death sentences than others, there is no uniformity in factors that lead to a sentence being commuted, and there is the real fear that innocent people may hang. And this is not the contention of human right activists opposed to the death penalty - some of the doubts have been expressed by judges themselves.

In 2012, 14 retired judges wrote to the President, pointing out that since 1996 the Supreme Court had erroneously given the death penalty to 15 people, of whom two were hanged. In 2009, the Supreme Court admitted that it had wrongly sentenced 15 people to death in 15 years. Since 2000, it had ordered 60 death sentences.

"An error rate of 25 per cent is simply unacceptable," says Yug Mohit Chaudhury, human rights lawyer and senior advocate of the Bombay High Court. "A car manufacturer with such a high error rate would have been shut down in a jiffy."

Among those the judges' letter mentioned was Ravji. Also on the list was Surja Ram, hanged in 1997 for the murder of his brother, sister-in-law, their two sons, and an aunt over a land dispute in Rajasthan. The Supreme Court said the death sentence was another error.

"There can be no graver miscarriage of justice than this. The Supreme Court's admission of error was too late for them. They were hanged because of erroneous judgments," holds Prabha Sridevan, former judge, Madras High Court.

As the debate over the death penalty gathers ground - around 385 prisoners are currently awaiting either death or a successful appeal - it is becoming clear that the noose is often tightened around a neck that doesn't deserve it.

Legal experts point out that such judicial errors abound. If the Supreme Court bench had not realised the error in the Ravji judgment, more convicts would have gone to the gallows.

Take the case of Mohan Anna Chavan of Maharashtra's Kolhapur district. He was convicted of raping and murdering his neighbour's daughters by a trial court and sentenced to death. The high court and the Supreme Court confirmed his conviction and the sentence. He filed a mercy petition before the Maharashtra governor which is still pending. But the Supreme Court came to his rescue in 2009 by declaring the verdict an error, following the dictum of the Ravji case.

Often, though, the judiciary's hands are tied, for their judgements are based on what the police offer as evidence. That proper police investigation was not conducted in the Dhananjoy Chatterjee case finds support in a 2013 Supreme Court Judgement in Shankar Kisanrao Khade vs State of Maharashtra where the court, while passing a sentence in a similar case, observed that prima facie, the "criminal test" had not been satisfied in the sentencing of Chatterjee.

Chatterjee, a liftman convicted of raping and murdering an 18-year-old school girl in Calcutta, was hanged in 2004.

Exactly 11 years later - he was hanged on the eve of Independence Day - a new study conducted by professors Probal Chaudhuri and Debashis Sengupta of the Indian Statistical Institute, Calcutta, has found several anomalies in the police investigation of the case. They contend that the murder could have been a case of an honour killing, and Chatterjee may have been innocent.

Legal experts also fear that there are occasions when the police frame people to make a case. "The classic modus operandi is to torture suspects until they sign blank sheets of paper or a confession," says Anup Surendranath, who as head of the Centre on the Death Penalty at the National Law University, Delhi, interviewed death row prisoners between June 2013 and January 2015.

He adds that the "confession" includes statements about where the weapon, body, etc. are hidden or thrown away. "The police plant such evidence as appears in the 'confession' and show it as having been recovered at the instance of the accused. So under the law those parts of a confession that lead to recovery of evidence are admissible and basically the police stage such recovery," says Surendranath, who resigned from his post as deputy registrar (Research) of the Supreme Court after the Memon hanging.

But the court has no option but to pass judgments on the basis of the evidence before it, feels former Supreme Court judge P.B. Sawant. "For a criminal justice system to work properly, three different institutions - the investigating agencies, the prosecution and the courts - need to work in tandem," he says.

That the time has come for a rethink is being echoed by many who wielded the gavel. "I think we need to take a relook at the rarest of rare doctrine as laid down in the Bachan Singh judgement," says Justice K.T. Thomas, former Supreme Court judge. Judges, he points out, look at what they think is the rarest of rare cases. "So the death penalty became judge-centric," he says.

Indeed, there is nothing to explain why a particular case invites the death sentence, and another doesn't, or why a sentence is commuted, and another is not - disparities highlighted in a study of Supreme Court judgments in death penalty cases from 1950 to 2006 ("Lethal lottery: The death penalty in India" [2008]) by Amnesty International and the People's Union for Civil Liberties.

Dharmendra Singh (2002) and Kheraj Ram (2003) were sentenced to death because they killed their wives and children, suspecting infidelity. The former was sentenced to life, the latter to death.

Vashram (2002) and Sudam (2011) murdered their wives and children because of "nagging". The former's sentence was commuted; the latter was sent to the gallows.

Mohan (2008) was sentenced to death for the rape and murder of two minor girls, having earlier been convicted twice. Sebastian (2010), described as a violent pedophile with previous convictions for molestation, kidnapping, rape and the murder of a young child, was given life imprisonment for yet another rape and murder of a child. In two cases of child sacrifice, the court commuted the death penalty in one but upheld it in the other.

That a sentence of death or life can vary from judge to judge, or bench to bench, was highlighted in a new study of 48 Supreme Court judgements on the death penalty by the Asian Centre for Human Rights. It pointed out that one judge's conscience differs from another's.

Chaudhury is scathing about this disparity. He points out that one Supreme Court judge had a "strike rate" of 73 per cent when it came to convictions, versus the average rate of 19 per cent. So an accused who appeared before another judge was four times more likely to escape capital punishment, he says.

"Would a death sentence appellant not be justified in asking, 'Am I to live or die on the basis of the constitution of the bench and not the evidence in the case'," he asks. "Getting a soft judge is like the Russian roulette."

Samir Goswami doesn't get into the technicalities of the judgement that sent Chatterjee to death. All that he knows is that he was an innocent village boy who married his niece Poornima.

Poornima's dream of living in a big city was cut short within 10 days of her marriage to Dhananjoy. Goswami's eyes fill up with tears when he sees her in a tattered white sari.

"Now people are saying he is innocent," he says, wiping his tears in his thatched home at Jaldoba village. "I feel happy that someone has spoken up."

The problem within

2009

The Supreme Court admitted an error of judgment in sentencing 15 people to death.

2012

14 eminent retired judges wrote to the President, pointing out that the Supreme Court had erroneously given the death penalty to 15 people since 1996

2015

Two professors of the Indian Statistical Institute, Calcutta, published a study that found glaring anomalies in the police investigation of the Dhananjoy Chatterjee case

2015

A study conducted by the Centre on the Death Penalty at the National Law University, Delhi, and the National Legal Services Authority, states that 1,790 death sentences were handed down by the trial court in the last 15 years

2015

India: Death in the name of conscience, a study by the Asian Centre for Human Rights, states that “conscience” varies from judge to judge, depending upon his “attitudes and approaches, predilections and prejudices...”