|

|

| STYLE STATEMENT: A living room and (below) a dining area in a swish yooPune apartment |

Imagine living in a 5,000 square feet apartment cocooned in green. You could dive into the swimming pool, play a round of tennis if you are game for it, puff on your Cohiba in the cigar lounge, or pamper your body at the Six Senses spa. And, of course, you never worry about domestic help. A central vacuum cleaning system gets rid of all dirt for you, if there is any, that is — for the house is sheathed with glass walls.

Whoever it was who decreed that money couldn’t buy happiness should do a rethink. The apartment in Hadapsar, a 30-minute drive from Pune, comes for Rs 8.5 crore.

But then, when you come close to a Philippe Starck, you have to pay a price for it. Often described as the property industry’s Prada, the celebrated French designer, along with John Hitchcox, is the founder of design studio Yoo. Starck, the toast of the discerning rich across the world, is doing the interiors of the premium project called yooPune.

The 62-year-old product designer is known for a line that ranges from spectacular interior designs to mass produced consumer goods such as toothbrushes, chairs and even USB drives. Starck, who became a celebrity designer soon after he designed the interiors for the private apartments of former French President François Mitterrand, is feted for turning commonplace items — such as a lemon squeezer — into a work of art.

Yoo, currently working on 25,000 apartments in 41 projects across 21 countries, sold 90 per cent of its residential apartment projects in New York City within just days of its launch. And now the Pune project — in partnership with construction and real estate company Panchshil Realty — is creating a buzz.

“Our first few projects here are high-end, but our philosophy is to add value where we can by improving the quality of design, layout and thought,” Hitchcox said during a visit to India a year ago. “I think there’s a real appetite for what we do here.” Negotiations are on for a similar project in Mumbai, while a yooGurgaon project has been finalised.

Sagar Chordia, strategic director of Panchshil Realty, says he decided to rope in Yoo when he saw a Starck building in Tel Aviv. In his Pune projects, he points out, the marbles come from Italy while the kitchenware, sanitary fittings, plumbing and waterproofing material are from Germany. “Though we are 10-15 per cent more expensive than other luxury segment projects in Pune, our designers are world class,” Chordia says.

YooPune, however, isn’t the only project that defines the future of boutique living in India. Restello, conceived by the UK firm Piercy Conner Architects & Designers, and developed by Bengal Shrachi Housing Development Limited in the heart of New Town, Rajarhat, close to the Calcutta airport, is aimed at creating an urban utopia. The steel facade allows for long uninterrupted living spaces while perforations filter the light and provide natural ventilation in the two-floor maisonettes.

|

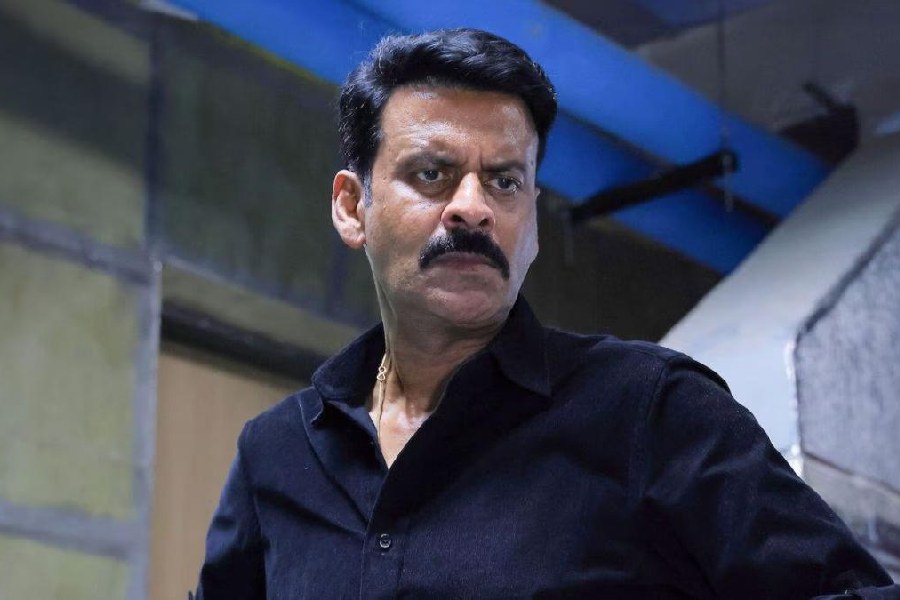

| DESIGN GURU: Philippe Starck |

Suddenly, real estate is no longer about high-rise buildings with chrome and glass. Some are looking beyond what’s merely good, wooing the best in the world.

“India has preserved the human way to live,” says Philippe Starck on his website. The project would be a way to enhance that feeling, he says.

Much before Starck, of course, there was Le Corbusier. His creation — Chandigarh — is even today upheld as a path-breaking example when it comes to defining architectural standards the world over, more than 50 years after the city was planned. “It set a new way of ‘thinking’ urban design and continues to inspire generations of architects,” says architect S.K. Das, who has designed a township in Indonesia.

A few years down the line, Joseph Allen Stein left his imprint on select buildings in Delhi, including the India International Centre and Unicef building, all around Lodhi Road in central Delhi.

“One can safely rename the Lodhi Road area as Steinabad, such was Stein’s contribution here,” says architect Anil Laul who trained under the American. Das seconds that. “Stein’s understatement of a building constructed with local stones in a well-crafted garden setting and with due regard for the historic Lodhi Garden can be considered a master stroke.”

But many see these as aberrations, maintaining that good architecture and Indian cities could never figure together in one single sentence. In general, Indian buildings have been abysmal — offices are like matchboxes stacked together, galleries and museums are closed in, and houses, simply chaotic. “Indian architecture witnessed a gradual deformity,” admits architect Prabir Mitra, who designed Ffort Raichak, outside Calcutta.” From an architectural perspective, post-independence India had surrendered meekly to bureaucratic indifference.”

The winds of change, however, are blowing at long last. “This can be attributed to a significant change in the Indian mindset,” says architect Dulal Mukherjee, the man behind Calcutta’s South City residential complex. “Now with changes in lifestyle, needs have changed. People have begun to look at the home as an extension of the self. Luxury has become a necessity; people want to live life kingsize.”

He elaborates that people are travelling more, and seeing spectacular buildings. “Everyone now would like to dwell in aesthetically designed sylvan surroundings.”

As a result, fine architecture is making its presence felt in the country, albeit slowly. Art and architect communities are happy that the Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron is designing the Kolkata Museum of Modern Art — meant to collect, preserve and exhibit fine art in the Indian sub-continent — on a 10-acre plot in Rajarhat. “The work of Harry Gugger (a partner at the firm) will set a benchmark for Indian architects. Herzog’s approach towards design is unique, its depth is amazing, and functional and technical analysis are a cut above the rest,” reaffirms Mukherjee.

Housing complexes across the country are also trying to make a design statement. Das’s Andrews Ganj housing in south Delhi is a case in point. Wide open spaces, such as walking precincts, squares and manicured lawns coexisting with vegetable garden patches, define the project. “There are no walls separating the blocks and the cluster reaches out to the city. This is what I call housing without borders,” says Das.

Calcutta has seen a few changes too. In his recent housing projects such as Highland Woods and Sankalpa in New Town, Rajarhat, Mukherjee seeks to blend the structure with the surroundings. “No matter how well you design a building, you cannot compete with nature,” he says. Accordingly, when he is on the drawing board he lets the design evolve from the nature of the landscape around it.

Architect Balkrishna Doshi’s design of Upohar — The Condoville, a Bengal Ambuja project off the Eastern Bypass in Calcutta, is in the same spirit. And yooPune may well underline a similar tryst between man and nature. India is being given a much needed facelift.