A young tribal couple is on the run. The two have murdered a rich man in their village and the army is looking for them. Uniformed men have surrounded the village and the forest, where the couple is hiding. Before long, the man is hunted out and shot in the back.

She is caught too. The army captain orders his boys to "do the needful". The soldiers rape her through the night, but in the morning, throw her clothes back at her. To appear before the captain, she must be "respectable".

What happens next is both miraculous and terrible.

The woman, almost a corpse, pulls herself up and throws her clothes back at them. She will show herself to the captain naked. The very men who had raped her the previous night, tearing her body into shreds, recoil from the sight. The captain cowers, but she walks steadily up to him, with utter contempt, and throws her body at him with all her might. There is nothing to be ashamed of. There are no "men" here. The young woman's name is Draupadi - or Dopdi, Dopdi Mejhen, as she is known among her people.

***

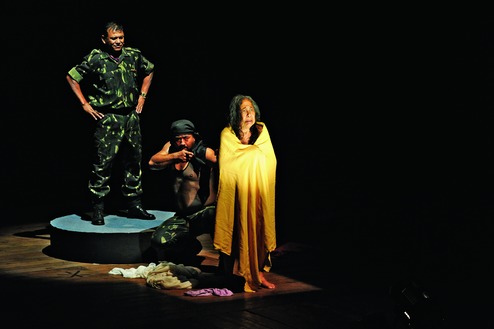

On stage, the actress who is playing Draupadi in the play of the same name is the renowned theatre actor Sabitri Heisnam. She is 73.

When her naked, aged body rises from her discarded clothes and falls like a blow on the astounded captain, an upheaval takes place. Nothing is so disturbing as a woman's body that refuses to be sexed as men want it to be, or shamed, or humiliated, or mutilated. This happened in the epics - the play echoes with Draupadi, the wife of the Pandavas; with the man-woman Shikhandi, who was used as a human shield in the battle of Kurukshetra.

At Gyan Manch, the auditorium in central Calcutta where the play is being staged, one witnesses an extraordinary moment. As the captain is felled by Draupadi's body, the audience falls silent. A co-actor wraps a housecoat around Sabitri's body, trembling from the act that has brought together many histories, many politics.

Draupadi was organised last month by the Pratyay Gender Trust, a collective for transgender women's rights, and Sanhita, a gender resource centre in Calcutta. The audience that evening is diverse. The play, based on Mahasweta Devi's story Draupadi, about a tribal couple that "rotates" between Birbhum, Burdwan, Murshidabad and Bankura to find work and comes under the influence of Naxalite ideologues, is performed in Meeteilon, popularly known as Manipuri.

Manipur, of course, has for decades remained under the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act or AFSPA - something that, its people feel, has brutalised the state.

***

A day after the performance, Sabitri is restored to her natural, jovial self. She is meeting us at the south Calcutta flat of a young scholar. She speaks in Meeteilon, with the help of an interpreter. She is "Ima" - Mother - to all.

Vivacious, playful, childlike, laughing all the time - she can giggle like a teenager - she is also mischievous, subjecting to her wicked wit even her husband, who had started it all.

Sabitri was married to Heisnam Kanhailal, the founder of the theatre group, Kalakshetra Manipur, and one of the most notable names of contemporary Indian theatre. Kanhailal, called "Oja" by all, passed away in 2016. Kanhailal and Sabitri's relationship could be one of guru and disciple, as well as of master and muse, with marriage thrown in between. She caught his eye when she was a young artiste in Imphal's commercial theatre.

In 1961, she first acted in a play by Kanhailal, with whom she would later elope. Together, they would create many theatre landmarks - and a new idiom for the Manipuri stage.

Kanhailal was always political. His theme was power - "the big dominating the small". Kalakshetra Manipur is remarkable for its repertoire of about 20-odd plays that were also attempts at reviving indigenous cultural traditions, drawing from nature. In this, Sabitri was indispensable.

"I can never live in the city," says Sabitri. Her performances are inspired directly by nature. Kanhailal exploited this affinity and her rich voice, to bring to his theatre a unique element.

He used to wake her up at dawn, she recalls, urging her first to listen to a dog bark or a chant and then to combine the two as a lament to be used in a play. The result was a long, low howl that almost becomes a song, at once eerie and beautiful. Sabitri sings it to a stunning effect this rainy afternoon.

She also performs a crow's early morning cries - even adding, after each shriek, a soft aftersound. She obsessively watches birds and animals for their movements and sounds, often surreptitiously, says her interpreter Usham Rojio, a scholar, with a smile. " Nisarga," she says. Nature is a friend and theatre comes from nature, from breathing, she adds.

One of their best-known plays, Pebet, uses nature brilliantly. Pebet is a Manipuri folk tale, but Kanhailal turns it into an allegory of Manipuri history by using a cat wearing holy beads around its neck as a symbol of the Vaishnavite Sanskritic cultural imperialism that struck at the roots of indigenous traditions.

But among all Kalakshetra plays, Draupadi perhaps remains the most talked about. It was conceived, like all his other plays, drawing from life around him, but Kanhailal found Mahasweta Devi's story the perfect fit for an idea he was struggling with.

After the performance, at Gyan Manch, scholar and critic Samik Bandyopadhyay narrated how it happened. One evening he was sitting at Kanhailal's residence at Langol, on the outskirts of Imphal, when Kanhailal pointed to the neighbourhood and said every house in the locality had lost someone, or suffered, while resisting the army.

Their own son had joined the struggle. A woman had been gangraped in front of her father-in-law and husband. Kanhailal wanted a play that would talk about this. It was then that Bandyopadhyay suggested Kanhailal read Mahasweta Devi's short story.

***

Draupadi was first performed in 2000. Soon after its initial performances in Imphal, it led to outrage and vicious criticism of Sabitri for appearing in the nude.

She says she was confused at first. "Am I doing wrong, I asked. I am not an intellectual. But I was not earning with my nudity. Besides, all my family was present at the performance," she said.

Then, in a strange way, things changed in July 2004, when an incident took place in Imphal that shook the nation. A group of 12 Manipuri mothers appeared naked in front of Kangla Fort with a banner that read "Indian Army Rape Us".

The Assam Rifles - the oldest paramilitary force in India - was stationed in Kangla then. The women were protesting the rape and killing of Thangjam Manorama, a young woman suspected of being a militant and arrested by the army.

Manorama had been shot 16 times in her genitals. "Indian Army Take Our Flesh," another banner had read. "Oja, who had once been criticised for the play, was now called a prophet," says Sabitri. "But we didn't inspire the protest. It was an echo of our play," she adds.

Appearing in the nude was her idea. In the first performance she had appeared in undergarments in skin tone. But she felt that was not powerful enough. So in the next performance, she appeared bare-bodied.

Kanhailal would later receive the Padma Bhushan, Sabitri the Padma Shri.

How does performing the role of Draupadi affect her? Sabitri says that a long, hard training enables her to go through it. This was the 18th or 19th performance; many have been staged in Calcutta. Shows in Imphal have become rare. Shows in general have become fewer. The previous evening was her last performance of Draupadi, she says.

She is not certain what will happen to Kanhailal's theatre and his legacy now. The young people of the group must work hard. Her husband was a man of great ideas, she says; she just carried them out. "He was ugly," says Sabitri. Then adds, "But beautiful inside."