Yet another National Akimbo Day has come and gone. Also known as the International Day of Yoga - the auspicious June 21 each year in the era of New India - the event is marked by patriotic citizens transforming themselves into a contorting, heaving mass led by their leaders - netas and babas - in prime locations. The popularity of yoga can be gauged by the fact that even dissidents, such as farmers protesting against falling prices, thought of choosing a special pose - the shavasana - to get their point across. This government brooks no other position.

But where and when did it all begin for Bengalis? This craze for a chiselled physique, stunts and, later, yoga? Unfortunately for the Prime Minister, who loves to claim credit for every wondrous creation - bridges, tunnels and what not - he has been beaten to Bengal's yoga crown by someone else.

Tucked inside Sukia Street is one of Calcutta's oldest colleges, imparting to its students the myriad tricks of physical education. Gunomoy Bagchi, the man who had memorably described his muscular body as a "temple" in Satyajit Ray's Joy Baba Felunath, would have approved of Ghosh's College of Physical Education. The institution was founded by the legendary Bishnu Charan Ghosh - Bishtubabu to his legion of admirers - in 1923. In 1936, the suffix - Yoga Cure Centre - was added to the name of the college. Its renowned students include, among others, Monotosh Roy and Manohar Aich.

Ghosh started his college at a time when the fervour of nationalism had left a deep imprint on not just the collective psyche but also on India's sporting culture. The Raj, as has been suggested often, had been condescending towards the "non-martial" races. The idea of the puny, pen-pusher Bengali had taken root. One of the strategies adopted by nationalist leaders and philanthropists to challenge such ethnic stereotyping as they went about ushering in Bengal's nabajagaran, or renaissance, was popularising sport that demanded physical fitness and endurance. The consequence was the birth of several community centres, which taught not just physical education but also other games such as kushti and laathi khela. It is significant that opposite Sukia Street lies another landmark address: Pulin Behari Das's house on Vidyasagar Street where students learnt how to wield the stick, wrestling and sword fighting.

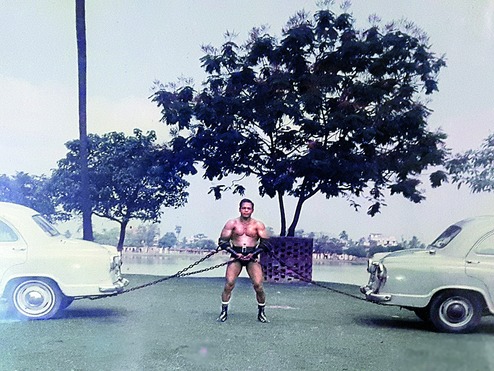

A visit to Ghosh's college would be incomplete without a peep into the room where Bishtubabu gave lessons in fitness. Mounted on the walls are old photographs that offer rare glimpses of another time. In one photograph, Bishnu Charan Ghosh is seen with Rabindranath Tagore. Below it is another frame, showing Dharmendra grinning in the company of two others. There are numerous pictures of physical stunts: Ghosh's students have been captured on film as they go about performing such astounding feats as breaking iron chains, bearing the weight of elephants on their chests, balancing iron balls and so on. One photograph is of a still from the footage from Japan's Fuji TV. In it, Bishtubabu is seen looking intently at his son, Biswanath, performing a difficult stunt with a road-roller. A popular American television show, That's Incredible, featured Ghosh Jr as well.

It is a pity that such rare photographs are yet to be digitised. For what is on offer here are more than just candid shots of icons. These images are the markers of an era in which stunts were as popular as mass sports like football - cricket, modern India's obsession, was in its infancy then - and occupied a niche in the world of public entertainment. There is a dearth of research on the history of public, as opposed to cinematic, stunts. (The acts performed in circuses are being excluded in this context.) Several intriguing questions can be answered by such scholarship. For instance, how were these spectacles organised? What were the mechanisms of their mobilisation? Was the audience charged a fee? What did the crowd take back from what they witnessed? Members of the Ghosh household, who continue to take an active interest in the college's functioning, could not, however, throw light on these queries.

The narrative in modern times has turned towards the therapeutic. Most students of the institution are interested in learning about the curative effects of yoga. Their enthusiasm goes well with New India's new found obsession with yoga. The competition is, however, stiff. Bona fide institutions, such as the one that bears Ghosh's legacy, are being challenged by therapy and wellness centres that claim to rid the body of even serious ailments.

The latter claim could be spurious. But there is no doubting the theory that Bengali men and women - Karuna Ghosh, Bishnu Charan's daughter, was an active participant - knew a thing or two about fitness and asanas well before Ramdev built his empire. The proof lies in a yoga college with a room full of images that tell a little-known tale.