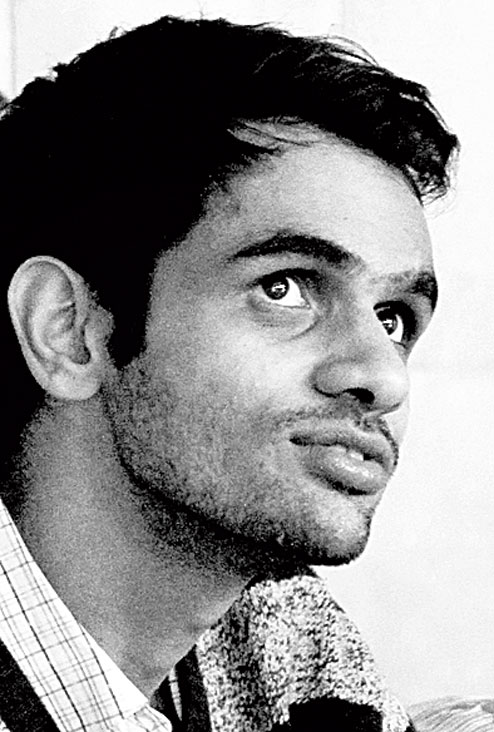

One of the first things the police made Anirban (Bhattacharya) and me do, after we surrendered to the Delhi Police in late February, was to fill up a questionnaire: “What does azadi mean to you?” Funny as it seems, this was one of the questions that inaugurated our police interrogation. I was quite baffled. Was the Delhi Police playing a game with us, putting us through an essay writing competition? Quite scared at the time of arrest, I was expecting to be grilled about my supposed Pakistan visits, Jaish-e-Muhammad connections, 800 phone calls to all “troubled” parts of the world, the plan to hold meetings commemorating Afzal Guru across universities. So after all the grandiose and outrageous claims made about me on television, had it all come down to this — what I thought of freedom?

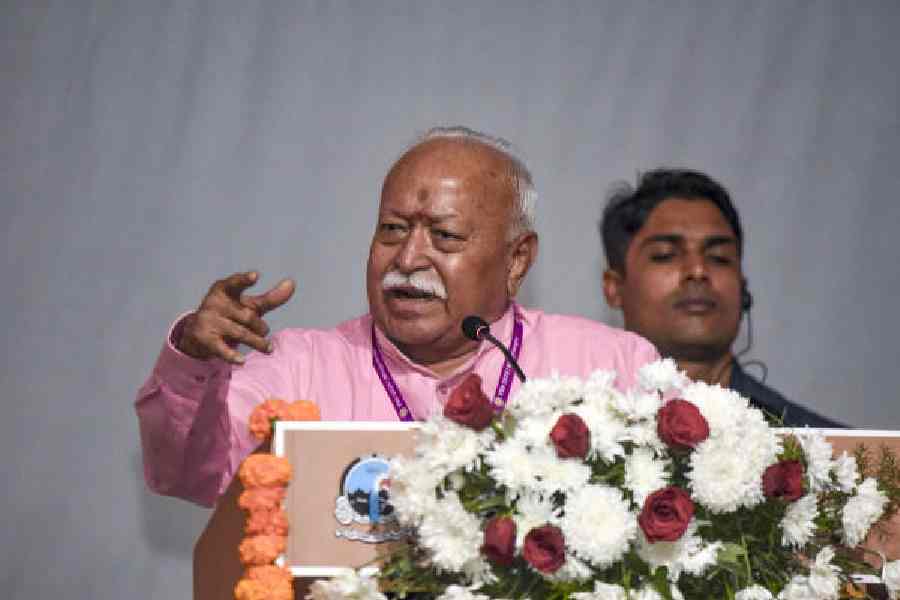

At the core of the entire JNU fracas is the criminalisation of free thought which is unfettered by the constructs of caste, religion and the nation-state. We are accused of, nay guilty, of “thought crimes”, as the RSS and BJP leaders and their hireling TV anchors declared. The mere harbouring of certain ideas is our criminal offence. As I put pen to paper that day, I wondered how my words on freedom were going to be used against me? Police custody — with all its very direct reminders of caste, religion and the nation-state — was not really the best place to express unfettered thoughts on freedom.

My sincerest apologies to the Delhi Police for not having given them the best answer on the profound concept of freedom. After months of contemplation, I now pronounce my thoughts on freedom, azadi.

I am not going to speak in absolutes. In real life and politics there is nothing called absolute freedom or for that matter absolute democracy. Freedom, as Karl Marx explained, is directly connected with those who control economic resources, political power and intellectual resources. During the build-up to the crackdown on JNU, a central argument given by the supporters of the present regime was that freedom of expression guaranteed by Section 19(A) of the Indian Constitution was not absolute. There had to be “reasonable restrictions” on it, which the very next section of the Constitution lays out. Rulers in all societies place these restrictions and its transgressions are strictly penalised. Pakistan does it through its blasphemy laws. We do through its more secular variants — Section 124(A) of the Indian Penal Code, the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act and their like.

To speak of freedom is to speak of power. Those on the right side of power, in all possible senses, have the freedom to say and do everything. A lynch-mob has the freedom to go and kill on the mere suspicion of the nature of meat in someone’s fridge. “Respectable” anchors have all the freedom to spread canards about someone’s non-existent Pakistani terror connections, only on the basis of a person’s identity. Leaders of the ruling dispensation have complete freedom to make hate speeches. And, of course, the police and paramilitary have complete impunity to kill and maim. As long as it re-affirms power, even questions are not asked. But these freedoms for the few can only be sustained by denying them to the multitude.

Just look at that “integral” part of our country. The complete azadi, guaranteed by the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act to troops to put down a recalcitrant population, is directly connected with the denial of azadi to the ordinary Kashmiris there. Last month alone, we have witnessed the way this absolute freedom to the security forces has grotesquely played out over the bodies of Kashmiris — 60 dead, over 200 injured and thousands maimed.

As I write this, I recall how on February 10 a senior Hindi news anchor was frothing with rage on TV, incensed with our views on Kashmir. He screamed at JNU students asking whether they think Kashmir has been enslaved. An important marker of any free modern society is freedom of the Press. I wonder what else to deduce, if not enslavement, from the recent mid-night crackdown on Kashmiri newspapers that were not necessarily toeing the official line from Delhi. What is it, if not affinity to power, that makes big media houses turn a blind eye to the fate of not just the ordinary civilian but even those from their own journalistic fraternity reporting from that conflict zone? It seems the pellets fired in Kashmir have blinded more Indians than Kashmiris.

Just a few days ago, a journalist from Bastar travelled all the way to Delhi to address a press conference. His name was Prabhat Singh and he had just stepped out of prison on bail after a year of incarceration on trumped-up charges. He had committed the same crimes his Kashmiri counterparts had — defying the diktats of the powers that be, in reporting from these war zones, a crime that bequeaths very stringent punishments today. He and three of his colleagues had earned the ire of the authorities. These assaults on the Press from our conflict zones are only symptomatic of the denial of several other freedoms.

There cannot be a more telling indictment of this than the tales of horror emerging from Bastar, which Prabhat Singh narrated that day. Sixty-nine years after the British left, is this how our freedom looks? Azadi for the mining mafia and their paid media? Deserted Adivasi hamlets, militarised forests and bullets through the heart of the republic with complete freedom for big companies to loot and plunder?

Those who have aligned themselves closely to the project of capital and the nation-state would question our obsession about these stories of the yesteryears. All societies — even the mighty and prosperous Americans — have had such a past. If they pretend ignorance of all that, what stops us from doing the same with our present, especially when a prosperous future beholds us? These are but a few costs we pay for the greater common good of the society as we march towards a Brighter, Freer and More Civilised future. Moreover, what good has come from keeping Dalits and Adivasis in their villages? It is the city of tomorrow, with its high-rise towers, malls, highways, metros and Make in India projects that they ought to be brought to. The military, as a former home minister insinuated a few years back, has only been sent to Chhattisgarh to bring them out of their museum-ised past and integrate them into this Indian avatar of the American dream.

One only needs to follow the outpouring of Dalit rage in Gujarat to understand how this fairy tale of capitalism is nothing but a cruel joke. And this is from Gujarat — that most investor-friendly state. The most oppressed — the Dalits and the Adivasis — are thrown out of their villages not to be absorbed by the city, but to be in turn thrown out again. Or be kept at its very margins and humiliated at every instance. That Dalits are still forced into the most degrading occupations such as manual scavenging and cleaning carcasses, and that caste-based occupations continue to exist, only reiterate the strong nexus between capitalism and caste, between market and Manuvad.

The video images of four Dalits tied to a car, stripped and flogged in full public view in front of a police station, continues to expose the grotesque bondages that characterise our society. Sixty-nine years after the British left, these thousand-year-old bondages are nowhere on the wane, they are rather tightening their poisonous grip. And that is exactly what the Dalits

of Gujarat seek to break. By throwing dead carcasses of cows in front of government buildings, they are simply refusing to remain enslaved by the historical burdens of caste-based occupations.

Babasaheb had called Hinduism a chamber of horror. Dalits for centuries have been condemned to enslavement in its dungeons amidst filth, faeces and carcasses. Today, they are marching in thousands out of that dark dungeon of horror to other possibilities of life. By doing so, they are not only materialising their own azadi, but ours too. We, who are equally condemned in various darknesses of the same chamber of horror, are being set free by every step the Dalits are taking forward. All our struggles of freedoms are after all intertwined with each other.

On August 15, in the very centre of our nation a few hundred Adivasis from Chhattisgarh, led by Soni Sori, will culminate their week-long march at Gompad in Bastar’s Sukma district demanding an end to the ongoing military offensive in the Adivasi heartland. The march of the fighting Dalits in Gujarat to Una will also culminate the same day. Braving bullets and pellets, the many hundred marches coming out on the streets of Kashmir will probably also have become larger by then. Despite the immense crackdown, the sweet sound of azadi — in all its different yet connected meanings — will reverberate through all these marches. Hundreds of miles away from these marches, from behind the bullet-proof glass screen at Delhi’s Red Fort, the Prime Minister would also share his thoughts on freedom. On this auspicious day tomorrow, azadi will be the central theme for both the hunter and the hunted.

Which of the two makes sense to us depends on where and how we align ourselves to power.