|

The wordsmith puts it well. If you can’t please everybody, Bob Dylan suggests you might as well not please anybody at all. For there are so many people, he points out, and you just can’t please them all.

When it comes to not pleasing people, Pankaj Mishra, 43, has been there, done that. His works — mainly his essays — make many of his readers turn a delicate shade of purple. He has been flooded with hate mail, been accused of spying for Pakistan, of hating India and more. But like another careful wordsmith, Mishra — author, novelist, essayist, journalist and now historian — doesn’t give a damn.

“If you take an unpopular stand, obviously you are going to be targeted,” he says. “It’s slightly worrying when you are not. That’s when you start to wonder if you’ve gone wrong somewhere,” he adds with a laugh. “I think the danger is when you start thinking that writing is essentially entering a popularity contest — you have to be loved by your readers. I think that’s when you become complacent.”

Mishra, indeed, is not entering a popularity contest. His new book From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia has already evoked criticism in some quarters — though it’s also warmly hailed in others. Writer Philip Hensher calls it blinkered in The Spectator; Ben Shepherd in The Observer says it’s erudite and engaging, while historian Mark Mazower lauds its “power to instruct and even to shock” in The Financial Times.

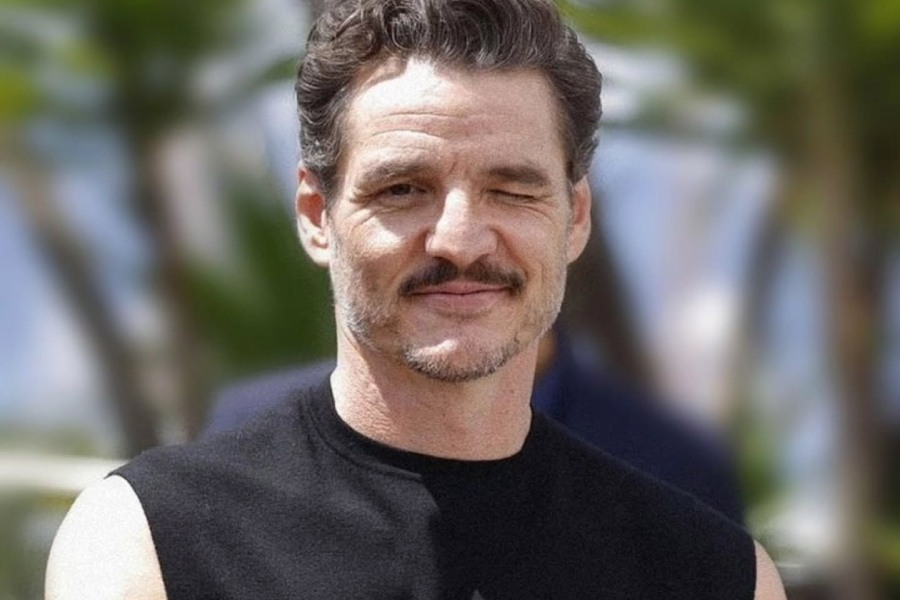

We are talking about the book in the coffee shop of a small hotel where he’s been put up for its Delhi launch. His eyes sparkle as he speaks in his soft, modulated voice, with just a little stress on an odd syllable here and there betraying the fact that he has been spending time in England.

The book — the idea of which, he says, started germinating in 2005 — looks at early modern Asian ideas that countered Western imperialism through the thoughts of his three protagonists — Jamal al-din al-Afghani of Iran, Lian Qichao of China and Rabindranath Tagore of India.

“I looked around to see if there was a book like this, and there wasn’t. There were biographies and history scattered with this and that but no one book that looked at this particular moment in history,” he says. “These were men in similar situations — they shared dilemmas and faced the same challenges in different countries.”

For his research, he consulted the London library and bought books by the dozens from Amazon. And then he transported his research matter, his laptop and his mind and body to Mashobra, a village just outside Shimla.

“I can revise everywhere, but the composition bits are all in Mashobra. I can work there for days on end without any interruption,” he says.

The Mashobra that nudges Shimla is the rich man’s summer retreat. Rows of houses, with manicured lawns bursting with hydrangea bushes, speak of a world that Mishra has been wary of. But his own house — once it was a flat above a cowshed and now it’s an adjoining house that overlooks his old abode — is where the village of Mashobra lives. “My village,” he says.

Mishra has old ties with Mashobra, which he first visited when he was 23. He was in Shimla — and sorely disappointed with the crowded hill town — when somebody told him about a picturesque village. So he took a bus to Mashobra.

“Then I saw this house, and said, such a lovely house, wonder who lives there. I knocked and it turned out the owners had built another little cottage on the other side of their apple orchard.”

That’s where he wrote Butter Chicken in Ludhiana: Travels in Small Town India (1995) — his first book. And that’s where he lives several months a year, when he is not in London with his publisher wife and four-year-old daughter, or travelling.

Mishra’s fondness for small town India is not surprising, for he grew up in places such as Jhansi, Akola and Betul where his father, a railways man, was posted.

His house, he recalls, was always full of books — from Dickens and Hardy to Readers Digest condensed novels and the ubiquitous Autobiography of a Yogi, which was once a part of almost every middle-class Indian’s bookshelf.

He remembers, in particular, reading Tagore. “I can’t read Bangla, but I love the sound of his poetry in Bangla. I love Rabindrasangeet — I have a huge number of recordings. There was a sizeable Bengali population in the towns where we lived. The first Indian poets and writers known to me, before I knew any in Hindi or Urdu, were Tagore, Bankim and Sarat Chandra. We were all Bangla fans.”

Young Pankaj read and read — but had little idea of what lay ahead. He didn’t know what he was going to do — all that he knew was what he was not going to do. “I was not going to join the government, for instance,” he says. “I knew I liked reading, but that’s all I knew.”

So after studying commerce in Allahabad, he moved to Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University because he had seen — and admired — the library there. He studied literature but says he was conspicuous by his absence in class. “I was such a mediocre student. I couldn’t actually get into anything apart from commerce. Which is, of course, not to say that I studied it with any degree of seriousness.”

Books, he stresses, happened by accident. Publisher David Davidar — then with Penguin India — wrote to him after he read a piece written by Mishra in a newspaper. “I had never met him. But he said he liked what I’d written, and would I like to write a book? And I said, yes, absolutely.”

So Mishra embraced the road not taken. “I must give my parents full credit for never really challenging me about this disastrous looking career path that I was choosing.”

His father, he’d said in an interview, may have nurtured literary ambitions. Did he? “There was certainly an unfulfilled desire to write. It’s more common that we realise. But clearly those ambitions were unfulfillable — there were no platforms, no publishing houses then. It was fantastical for them to dream — it was fantastical for people like me to dream — like that,” he says. “We carry in ourselves these unfulfilled dreams of our fathers and our grandfathers.”

Are his parents happy now that he has made a name for himself — and written several acclaimed volumes? “I think so,” he says, and then adds, “I hope so. They are very reticent about this matter.”

Reticence is clearly not a trait that Mishra’s inherited: his frank opinion on issues has often put him in the midst of raging controversies.

In November 2011, he got into a literary brawl with Harvard professor Niall Ferguson when he described Ferguson’s Civilisation: The West and the Rest as “gallimaufry” (gal 'môfre: A confused jumble or medley of things/A dish made from diced or minced meat, esp. a hash or ragout: Ed). Ferguson, in turn, demanded an apology for what he called character assassination.

Earlier that year, Mishra’s criticism of Patrick French’s India: A Portrait in a magazine led to another literary fracas. French replied with a biting rejoinder, pointing out that Mishra was married to British Prime Minister David Cameron’s cousin. “But he seems oddly resentful of the idea of social mobility for other Indians,” French wrote.

Mishra shrugs. “People told me about this — But I never actually read it. Life is too short. I never read the comments that appear at the bottom of a copy.” All those 57 readers’ remarks — 56 spewing hatred? He laughs. “I have been accused of treason, called an ISI agent and all that. Then the readers fight among themselves — at least they do so in The Guardian,” Mishra says. “I am always happy to enter into a conversation, a dialogue and debate — but this kind of stuff is just not interesting.”

His writings on Kashmir — 25,000 words in all — have spawned hate mail too. In his reports, he voiced the Kashmiri people’s belief that intelligence agencies were involved in the 2,000 killing of Sikhs in Chattisinghpora. How did he start writing on Kashmir?

“I had an argument with a very famous writer who is no longer with us — Nirmal Verma. He was very dear, I loved him. He and I were arguing about Kashmir, and there were others too. I was basically arguing that we must end our military occupation of Kashmir — which is what it is, and which is untenable. And then at the end of a very intense argument, we realised that none of us had been to Kashmir, we’d only gone there as tourists. So I decided to go there and do a long article, just to educate myself.”

In the publishing world, an interesting story often crops up when Mishra’s name is mentioned. As a young man, Mishra was working at a publishing house when he received Arundhati Roy’s then unpublished debut novel. He liked The God of Small Things so much that he promptly sent it to publishers abroad and to literary agent David Godwin. Godwin represented Roy and won her megabucks, while the Indian publishers cried all the way back from the bank. Did all this happen?

Roy, he says, was a friend — and he had bought the Indian rights to her book. “No way was Arundhati going to sell the world rights to the (Indian) publishers. When I left them soon after that, she took the book out, because she wanted me to publish it,” he says.

The Indian publishers, one can guess, aren’t pleased with Pankaj Mishra. Join the queue, guys.