Magic Pocket Saving Bank - reads the black-and-white print advertisement from 1916, exactly a hundred years before demonetisation became a thing. The visual is of a plump hand holding what looks like an inhaler with calibrations running along its side. The gist of the accompanying text written in Bengali is: If you want to save money, purchase this pocket bank. Once you have collected ten rupees, it will pop open. Attractive and finished with bright nickel plating, its price with tax, is all of one rupee and two annas, an anna being one sixteenth of a rupee.

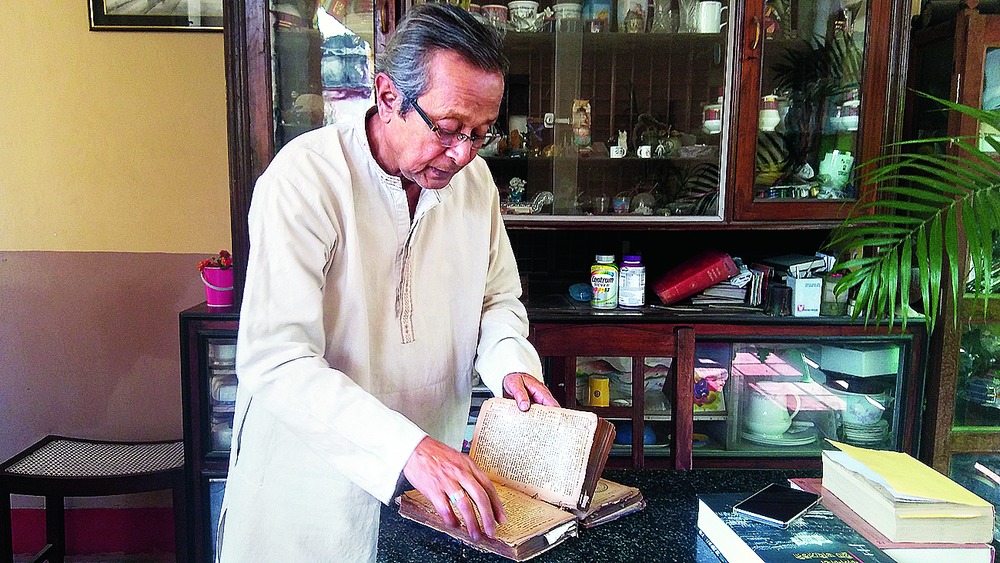

Flipping through the pages of the Kalikata Street Directory 1915, published by P.M. Bagchi & Company Private Limited in 2015, feels a bit like time travelling. The nearly 800 page book, which is really only a slice of the original P.M. Bagchi Directory Panjika, was resurrected with value additions by Jayanta Bagchi.

"The panjika or almanac was the most potent advertising tool of the late 19th century," says Jayanta, who is the current boss of P.M. Bagchi & Co. Back then, near about this time of the year, when the pages of the calendar fluttered excitedly around Bengali New Year's Day, the businessmen and the middle-class Bengali waited impatiently for the panjika. It listed their festivals right down to the last hour and also served as a shopping catalogue.

There were quite a few of them in the market; but some fell short on quality, while others consistently failed to meet the deadline - Poila Baisakh. That was why Jayanta's grandfather and founder of P.M. Bagchi & Co., Kishorimohan, thought up a double-barrelled product to vanquish competition.

Image courtesy: P.M. Bagchi & Company Private Limited

Not only did Kishorimohan publish a panjika, he also yoked it with an exhaustive all-India directory that tabulated by region every possible information a person might need - a list of the who's who, government offices, a Calcutta street directory, a section on steamers and post offices, a chart on the expenses of fighting a case in the high court, and so on and so forth. It was Yellow Pages meeting Google Maps. It was also a how-to-book full of home remedies for niggling issues like the stomach ache or acidity. "There were also DIY tips for everyday necessities such as making candlesticks or regular phenyl," says Jayanta.

That was 1899. Bengal was still undivided. The chunky panjika had a robust annual circulation of two lakh copies.

At the core of the 2015 reproduction is essentially the street directory of Calcutta as it was then, post-World War I. Street by street, resident by resident, right down to names, house numbers, dwelling types - mess or hostel or to-let - temples, shops, parks, colleges, churches...

"Take a look at the entries under Sukia Street," urges Jayanta. The street was named after an Armenian lady, Sukhias Bibi, famed for her generosity. Among its then residents were - Kailashchandra Basu, CIE, the first Indian doctor to be titled "Sir" at No. 1; Upendrakishore Ray at No. 22; Mokhhada Ray, Lady Doctor at 39/1; and Mondol & Co. Tailors and Bisheshwar Dutt, goldsmith at 39/5.

How Kishorimohan went about his exhaustive research is not known. He died when son Kalishankar was 10 and the great backstory died with him. But Jayanta spent a dogged decade on the value addition. He incorporated street histories and bio notes of the who's who habiting them. "But some things I couldn't find. For instance, I have no idea who Akhil Mistry of Akhil Mistry lane is."

Pouring over the pages you will learn that Lord Sinha Road used to be Elysium Row. Metcalf Street was Zigzag Lane.

Image courtesy: Kalikata Street Directory 1915, published by P.M. Bagchi & Company Private Limited

The book is bereft of commentary, but the facts speak in an olden tongue, conjure a picture of another time, another life. The anomalies lend a touch of humour. For instance, while most residents are listed by name, you will come across the occasional mention of a Chinaman at House No. X or a Madraji (Madrasi) at House No. Y. The unfamiliar spellings and pronunciations possibly the reason behind the generic nomenclature.

The listicle is punctuated with rare photographs such as the Howrah Bridge in the making, more advertisements - Joubanbahar Churi, nababi jorda (tobacco), The New Infant Primer by Charu Chandra Paun, varieties of perfumes with poignant catchwords such as Forget Me Not. And at the tail end is a map of the city dated 1900. It seems a shame that such a piece of assiduous historiography should remain a prisoner of language.

What about Sooterkin Street in general and No. 6 in particular, the address of The Telegraph? No. 6, it seems, was the address of a Cabral & A.D. Regel. Nothing more is known. At No. 17 there was a stable. And Sooterkin? "I have searched and searched, but in vain," says Jayanta and points to the dictionary. One of the meanings is sweetheart, from the Dutch word zoet meaning sweet.