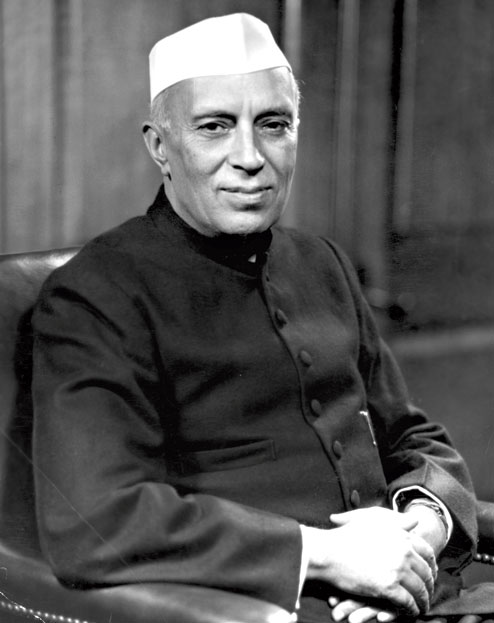

His trusting nature, it has been said, was a weakness in Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru... There are those who start on the basis that a person can be trusted until shown to be otherwise, and those who start with scepticism. Nehru clearly belonged to the first kind of people. A photograph taken in the late 1940s by the Calcutta-based photo-artist Jayant Patel has Nehru and Sardar Patel looking at a piece of writing. Standing in a close knot, Nehru is the very picture of trusting optimism, Patel of cautious pragmatism. Nehru seems like he has accepted what he is reading, Patel is giving it a close look. While Nehru trusts, Patel seeks evidence. While Nehru seems to be ready to believe, Patel seems to want proof...

By and large (a phrase, incidentally, that Nehru would use quite often), Prime Minister Nehru's trust in people was not betrayed. In other words, he did not regret the confidence he reposed in people. In a word-counting essay only representative descriptions are possible. So I will choose here, from among the many persons Prime Minister Nehru trusted, by instinct, to do right, three who just happen to be Malayali: V.K. Krishna Menon, an old friend and "his" first high commissioner in London, K.R. Narayanan (K.R.N.), who rose to be President of India, and M.O. Mathai, his private secretary. Menon and Narayanan were slightly acquainted with each other in London. When Narayanan finished his course of study in London with a First Division, the then small Kerala community there threw a party in his honour and high commissioner Krishna Menon was invited to be the chief guest. Leaning on his walking stick at the doorway Menon said to him, "So, Narayanan, I hear you have got a First. You know, some people get it by a fluke." If Narayanan was staggered it was only for a moment. He responded with, "Is that how you got yours?"'

K.R.N.'s term at the London School of Economics (LSE) is deservedly celebrated for the equation he enjoyed with the cerebral but morally intense Harold Laski.

I was privileged to serve President Narayanan as his secretary and once, while returning from Parliament House to Rashtrapati Bhavan with him after his ceremonial opening of the budget session in 1999, he related to me the following: "When I finished with LSE, Laski, of his own, gave me a letter of introduction for Pandit ji. So on reaching Delhi I sought an appointment with the PM. I suppose, because I was an Indian student returning home from London, I was given a time slot. It was here in Parliament House that he met me. We talked for a few minutes about London and things like that and I could soon see that it was time for me to leave. So I said goodbye and as I left the room I handed over the letter from Laski, and stepped out into the great circular corridor outside. When I was half way round, I heard the sound of someone clapping from the direction I had just come. I turned to see Panditji beckoning me to come back. He had opened the letter as I left his room and read it. 'Why didn't you give this to me earlier?' 'Well, sir, I am sorry. I thought it would be enough if I just handed it over while leaving.' After a few more questions, he asked me to see him again and very soon I found myself entering the Indian Foreign Service.'

***

Nehru's trust in Krishna Menon belongs to a different category altogether. Political analysts have tried to decode it with the axe of frontal assault and the nail-file of curious probes. It is clear that Nehru's confidence in Menon was instinctive and intellectual, a matter of feeling and of reason...

No two men could be more different and think more alike than Nehru and Menon. They shared a sense of history that wanted to see India count. They resented, with passion, any slights to India, be it by "small" neighbours or by "big" powers. The fact is Nehru could be no less angry if not angrier than Krishna Menon, but was careful in the way he expressed it. Krishna Menon was sharp in his language.

Far more difficult to appreciate is Nehru's trust in M.O. Mathai, his private secretary who joined him as India was becoming free and worked with him, almost like a shadow, for nearly fifteen years. Before I say something by way of an attempted analysis of this trust, I may be allowed an anecdote. Like most urban children, I went through a phase when stamp collecting was my hobby, my passion. My father used to get a modest number of letters everyday and the envelopes used to become my property, along with the stamps on them, coming in rich and colourful variety from different nations. When my father died suddenly - I was about twelve then - my stamp collection came to an abrupt halt... One day someone said to me, perhaps mischievously: "Why don't you ask Pandit ji to send you a small number of stamps each month? He was such a good friend of your father." I was a little abashed by the thought: Panditji... But then a kid is a kid and a passion is a passion. And this particular kid, a future bureaucrat, was sufficiently clerical of mentality even then. I figured that my writing to the PM with such a request being out of the question, I should try a less absurd proposition and must go to the proper channel. So, getting the contact details for his private secretary who, I gathered, was a certain Mr M.O. Mathai, I sent to that, to me, unknown functionary my hand-written rather plaintive request. The very next day, I got a fat bundle of stamps drawn from the envelopes of the prime minister's daily dak, hand-delivered at home...

I never ever saw Mr Mathai and very soon forgot all about stamp collecting. But looking back, I find that episode very revealing. Here was a man who meant something to his boss. He must have had something in him, at the very least, a sharp brain, to make him so valuable to the PM, so essential to his office. I therefore hold it to be a pity beyond words that circumstances led to M.O. Mathai's turning into a sour individual whose reminiscences, perhaps teased out of him by Nehru-baiters, ended up as little more than potsherds of his broken ego.

M.O. Mathai is the Malvolio in Nehru's Twelfth Night, distrusted, disliked, and ultimately, self-demolished. He could have become an editor and commentator, giving invaluable analyses, documentations, supported by sources both published and unpublished, of the Nehru years, that would have been the equivalent of the Transfer of Power papers.

Excerpted from Nehru’s India: Essays on the Maker of a Nation; Edited by Nayantara Sahgal; Published by Speaking Tiger, New Delhi, 2015; Price: Rs 399