|

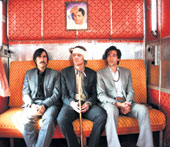

| India unlimited: (Top, from L to R) Jason Schwartzman, Owen Wilson and Adrien Brody in a still from The Darjeeling Limited; (below) Wes Anderson |

|

Teen Kanya it is not. It’s about three estranged brothers instead. But director Wes Anderson says his latest film The Darjeeling Limited about three brothers trapped together in a train compartment rattling across India, owes a lot to Satyajit Ray’s luminous triptych of three young women.

Anderson’s interest in India dates back to a childhood friend whose family was from Madras. He read Ved Mehta, saw Jean Renoir’s The River and Louis Malle’s documentaries. But before all that there was Teen Kanya.

“I think I liked the picture on the cover,” says Anderson who kept seeing the film in the foreign language section of the local video store near his father’s house in Texas. He finally rented it and was hooked. “I really responded to the characters. Ray wrote great stories, had great visuals and did great music.”

The Hollywood film, released by Fox Searchlight, is currently being screened in US theatres. And Anderson — famously described by director Martin Scorcese as “the Next Martin Scorcese” — sits in a San Francisco hotel, holding forth on the role that music played in Ray’s films.

Much of that music shows up in The Darjeeling Limited — from Vilayat Khan’s score for Jalsaghar to Ravi Shankar’s music for Pather Panchali and Ray’s own compositions for Charulata. “I had this compilation CD of Ray’s music,” he says. And Anderson thought a cue from Jalsaghar fit the beginning, and the music from Charulata was just right for a particular scene.

He despatched music supervisor Randall Poster to Calcutta where he met Ray’s director son, Sandip Ray. “And I guess we passed the test,” laughs Anderson, the director of Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou.

“It was really the soundtrack of our day,” says Roman Coppola, who co-wrote the film with Anderson. Coppola’s cousin, Jason Schwartzman, who plays the youngest brother, Jack, and also co-wrote the script, agrees. “The music really makes me nostalgic. We listened to it so much,” says Schwartzman, lounging on a couch, his feet up on a table.

For the trio, like their characters, The Darjeeling Limited was their first passage to India. “The script became an accumulation of our experiences in India,” says Anderson. “For example, we had to ride three abreast in an autorickshaw and that found its way into the movie,” adds Coppola. “Or we’d take the script to act it out in a temple and that would become the temple we would shoot at,” says Schwartzman.

Sometimes it was more than just the temple. Anderson remembers going to a temple and meeting the man who took care of it. “Then we ended up somehow in his apartment. We met his son and he had a toy gun in his hand. And he ends up in the movie.”

It’s not just one boy either. Anderson says he quickly discovered the cardinal rule of shooting in India — “you cannot control India, you have to embrace it.” In one shot the three brothers (Jason Schwartzman, Adrien Brody and Owen Wilson) were crowded on a ledge overlooking a cricket field. Suddenly a man walked up from behind Anderson and started moving towards the ledge. Even as Anderson went “Hey, we are shooting” the man calmly walked into the shot. “He just had to go somewhere and he wasn’t about to be slowed down by the scene,” remembers Anderson with a shrug. He kept the shot. “You look at it now and it’s so smooth you’ll think some assistant director told the guy ‘Go’,” he says. “Respect for authority only extends so far in India. I loved that. And the resistance to authority is done with a smile. Often.”

Anderson had his own encounters with Indian authority, probably not always with a smile. His producer had to wrestle with the bureaucracy of the Indian railways. Producer Lydia Dean Pilcher had shot one day on the train for The Namesake but Anderson wanted to rent 10 coaches and an engine for three months, strip them down, build their own interiors and run it on a live track. They miraculously managed it and created some kind of a cross-breed of the Orient Express with Rajasthani motifs à la Palace on Wheels, complete with a seductive coffee-chai-or-me stewardess who looks South Asian but speaks with a suspiciously British accent. But then, actress Amara Karan is a Sri Lankan Brit who’d never been to India before.

While most Western films made in India obviously struggle with the exotic factor, Anderson says he quickly realised that “as the foreigner he was the exotic one” in India. The Darjeeling Limited might come with the usual caboose of cows wandering the streets, snakes and sadhus, but as Anderson points out, it is the story of Western tourists in India for the first time.

“Our experience of India is limited but we fell in love with the country,” says Anderson. “And the film is authentic from our point of view.”

Coppola points out that much of the crew is Indian and the team took pains to use local artisans to paint the elephants on the train and use traditional fabrics and prints. Irrfan Khan has a small role as a villager, but most of his co-villagers were real villagers shot in their own clothes in their own houses.

But authenticity has its limits. The Darjeeling Limited never even gets to the Himalayas, remaining instead in the Sonar Kella lands of Jodhpur and Jaisalmer. Even the mountain nunnery where the last scenes are set were actually shot in the hunting lodge of the Maharana of Mewar in Udaipur.

So why Darjeeling? “I just liked the word,” admits Anderson. “I had wanted to shoot the end in Darjeeling. But I went there and decided against it. But I remembered Ray’s film Kanchenjungha. Satyajit Ray was one of my inspirations for wanting to make movies. So I kept the title as a reference to the original inspiration.”