Tragedies are made in heaven; earthly settings merely showcase the craftsmanship that has gone into their making. Robinson Street in central Calcutta cannot be called crooked, but it has always been a little off. The 75-metre-long stretch surrounded by the city's smartest streets - Park Street, Loudon Street, Theatre Road, Rawdon Street - has always been a bit of a wallflower. It was named after an erstwhile police magistrate of the city, Charles Knowles Robison.

Robison is the architect of the very Grecian Metcalfe Hall on Strand Road and naming a street after him would have been a neat tribute, except that by some twist of the tongue Robison Street came to be known as Robinson Street.

According to the Kalikata Street Directory 1915, an H. Cowley lived at No. 1 Robinson Street and a T.E. Trombley at No. 2. But long before it came to be known as the house of horrors or the site of the kankal kanda, No. 3 Robinson Street had a how attached to it. If you go by the 1915 directory, the house originally belonged to a D.P. How.

The kankal kanda, or the skeleton episode, was this. In 2015, police found one Partho De cocooned in his apartment on Robinson Street for several months with the skeletons of his sister and two dogs and the charred body of his father. There were murmurs about necrophilia.

"Partho never liked the Robinson Street house," says Ishita Sanyal, psychologist and founder-director of Turning Point, the mental rehabilitation organisation, where Partho was admitted from 2016 to the time of his death earlier this year. "He wanted to live in a huge house, his dream house. In his mind, the house on Robinson Street was inextricably linked with the beginning of all problems in his life," adds Ishita, who is putting together a book on Partho.

Ishita met him first in 2016, when she was summoned to Mother House, the headquarters of the Missionaries of Charity. Following his arrest and treatment at the state-run Pavlov Hospital, Fr Rodney Borneo of the Archdiocese of Calcutta had requested her to take Partho in.

Ishita says it did not occur to her to turn away Fr Rodney, but she did take a week's time to sound out parents and guardians of the other students of Turning Point, most of whom suffer from some kind of mental illness or the other, most commonly schizophrenia. Around this time, she was also invited to visit the Des' residence at Robinson Street.

The four-storey house built on around 20 cottahs had been purchased by Partho's grandfather, Gadadhar De. It was reportedly sold to a promoter for good money months before Partho's death, but so far the structure remains untouched - at least from the outside.

The entrance gate is imposing but not welcoming. There is something of a jail about its appearance, and the chain and the lock wound around it to keep away trespassers only enforce that impression. As far as the eye can see there is a longish avenue leading to the building entrance. And standing at attention are a couple of youthful deodars and one sinewy banyan tree.

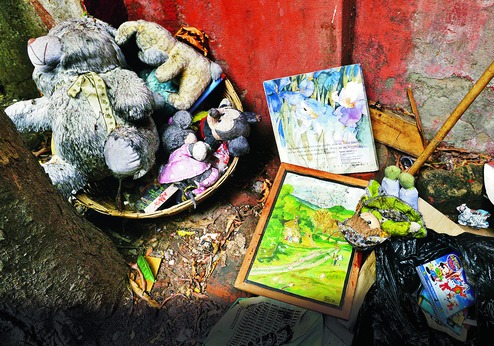

Says Ishita, "My first impression was - what a fractured set-up! You enter [the second floor], there is the dining room. To its right, Partho's father's room and bathroom. To the left of the drawing room, the room Partho and Debjani shared. On the walls were framed photographs of Joyce Meyer [described in Wikipedia as a Christian author and speaker] and the floor was dotted with plastic bundles - clothes, toys, books."

The last many months of his life, before he was found dead in Kidderpore's Watgunge area, Partho had started writing his memoirs. "He would keep mailing me portions," says Ishita.

Ishita says Partho's writings had an even, benign tone. He wrote of his childhood spent in Bangalore: "We had a very big mango tree in our front lawn... We would get a person to climb the tree and drop the mangoes, while two other servants held a cloth below... My mother would make pickles from them (sic)."

In the meantime, Partho's one-on-one counselling with Ishita intensified. These outpourings were more fervid. He spoke about how after having lived in Delhi, Bangalore, and Salt Lake in Calcutta, the family had moved to Robinson Street when he was in college, after his father was cheated in his business by his partner. According to Ishita, he spoke of Robinson Street as if it was this dark underworld. His controlling grandmother was Hecate; his fiercely protective mother who did not let the family mingle with outsiders, the human equivalent of Cerberus; and his piano-playing, spiritual sister, Persephone or even Lethe.

A feature film titled House on Robinson Street is in the works. Partho knew of it. He worried about its content because he had apparently told Ishita that he meant his memoirs to be the basis of a counter film.

Ishita says she wants her book to complete what Partho had begun. She is also working on a documentary on him with Abhishek Ganguly. "There is a perception about Partho that I feel I must clear," she says. "The media coverage made the gruesomeness the focus."

And is there something more?

Throughout the interview Ishita has spoken about the different sides to Partho that she has seen. Resilient side. "He talked us into letting him deliver spiritual talks to the other students." Caring side. "Once he tried to rescue a kitten and it scratched him. Instead of getting angry, he reasoned with the others that it was scared." Need-to-belong side. "He was delighted when a colleague invited him home. 'I have been invited to his home,' he kept repeating."

She reads out an entry from Partho's diary. He was reliving the death of his sister. "For two-and-a-half days, I neither ate nor drank anything. I too wanted to pass away... Then on the third day, I gathered myself together and started living again... I started reading our spiritual Guru Joyce Meyer books (sic)."

Ishita continues: "Do you know he spoke about how he placed the dead Labradors side by side, their paws over one another, so they wouldn't be lonely in death?" Then adds, "Partho had schizophrenia, but he was not a monster."

It seems Partho was keenly aware that people responded to him as " kankal kander Partho". In the diary entries immediately before his death, he had scribbled - I want to be Partho again.

That evening when Partho died, Ishita was not in town. There had been a birthday celebration of a student at Turning Point and the man who was Partho's caregiver-cum-attendant was asked to take some food to Partho. That is how he came to be found, lying dead, charred like his father.

It is Ishita's guess that if at all it was a suicide, then Partho must have read something online - his laptop was open - that had disturbed him. Around that time, a man in Bhopal had murdered his girlfriend and his parents and certain sections of the media had drawn parallels with the Robinson Street tragedy. Who knows, perhaps the comparisons caused his newfound self-love and self-confidence to flounder, suggests the psychologist. Who knows, perhaps in that split second he had been transported to No. 3 Robinson Street.