The Guest @ 7days

The past has always been a contested terrain in India, even elsewhere. Every one of us has an opinion about it like most of us have about cricket. It is immaterial whether we ever played the game or not. We have lived in this sort of India happily, often getting into playful debates about each other's views regarding the past. Lately that playfulness seems to be in danger. Almost 200 years ago, James Mill divided Indian history into three periods: Hindu civilisation, Muslim civilisation and the British period. This is one of the many gifts the colonial British left behind for us. They projected 2,000 years of golden age for the first, 800 years of despotic tyranny for the second, and a supposed modernisation under the British. This division also assumed Indian society as made up of separate religious monoliths - Hindu and Muslim - who were always mutually hostile. This periodisation and characterisation became axiomatic to the interpretation of Indian history. It worsened from the early 20th century onwards, with the emergence of communalism and the final Partition of the country in the name of religion.

Unfortunately, we carried these prejudices into independent India and kept perceiving our medieval past with angst and disgust. That's not terribly surprising because we inherited a colonial history which was more like a record of sectarian strife. It came in handy for certain political formations which have been using the past to settle scores in the present. There is a deep fallacy with this manner of reading and interpreting the past, which is also referred to often as the Whig interpretation of history. What happens, in effect, is that history begins to be read and consumed with one eye on the present. This is what Herbert Butterfield (1900-1979), who invented the term Whig interpretation, called "unhistorical history writing". However, in India these days, the past is being seen with both eyes on the present. Our obsession with the past 800 years of history has acquired new dimensions. We have begun to not just question history writing in partisan ways but have also begun to outrage on fiction from the medieval era.

The violent controversy raging around the legend of Padmini is the latest example of our fixation with the medieval past. We seem to have completely, and deliberately, blurred the distinction between what is history and what is only lore or fiction. Padmini was not a historical character, and the story around her is a fictional legend, no more. It is a known fact that the character of Padmini was conceived and created by Malik Mohammad Jayasi in 1540 in his famous poem called Padmavat, written in Awadhi but in Persian script. Jayasi's Padmini was a princess from Simhala-dvipa (Sri Lanka). In modern terminology, it was a historical fiction, which had historical characters like Alauddin Khilji and Rana Rattan Singh. No medieval historical record alludes to her existence before Jayasi's Padmavat. Amir Khusrau, who accompanied Alauddin Khilji in his expedition against Chittor, does not refer to it. Even Jayasi never claimed that he is chronicling history. According to The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909, "In the final verses of his work, the poet explains that it is all an allegory. By Chittor he means the body of man; by Ratan Singh, the soul; by the parrot (Hiraman), the guru or spiritual protector; by Padmavati, wisdom; by Alauddin, delusion, and so on."

.jpg)

No contemporary historian, including the most authoritative ones on Rajasthan like Gauri Shankar Ojha mention anything about Padmini. R.C. Majumdar also ends his short two-page account of Padmini by saying that "it is impossible, at the present state of our knowledge, to regard it as a historical fact". As far as I know, nothing new has emerged on the issue since.

Legends do get created in history, both around historical as well as fictional characters or episodes. Anarkali is a well-known character from the Mughal period. But the majority of serious historians consider her a fictional character, which is indeed what Anarkali was. She has a market named after her in Lahore and also a tomb. The 1960s Bollywood blockbuster, Mughal-e-Azam, immortalised her. But none of this can add up to make Anarkali a historical character. The famous Lucknow writer Abdul Halim Sharar, who wrote the original story about her, called Anarkali a fictional character. Yet in popular imagination she really dared the might of the Mughal emperor. It is no surprise that Padmini acquired great prominence in the bardic chronicles of Rajputana. Getting into the academic debate on the issue means no insult to either Rajput or Hindu psyche. It is also not a glorification of the medieval despot Alauddin Khilji. His depredations from Rajputana to Deccan are no fiction, they are all well documented in historical records.

The assault on Sanjay Leela Bhansali by some goons was reprehensible indeed, but I am more appalled at the communalisation of the entire issue. The whole episode reiterates how the present draws on the past not necessarily always to better comprehend the past but to use the past to legitimise the present. It is one more convenient ploy to polarise people. Giriraj Singh, our Union minister, alleged that Padmavati was portrayed in a poor light "because she was a Hindu". The outrage on social media is simply incomprehensible; hundreds of people even dared Bhansali to make a film on Prophet Mohammad.

This is not the first time that we have outraged on filmmaking about the past. We have done that earlier several times and, given the direction some of us are traversing, will surely do that again. It is one thing to study and learn from the past but to live in the past is a dangerous game. It is immaterial whether that past is historical or fictional.

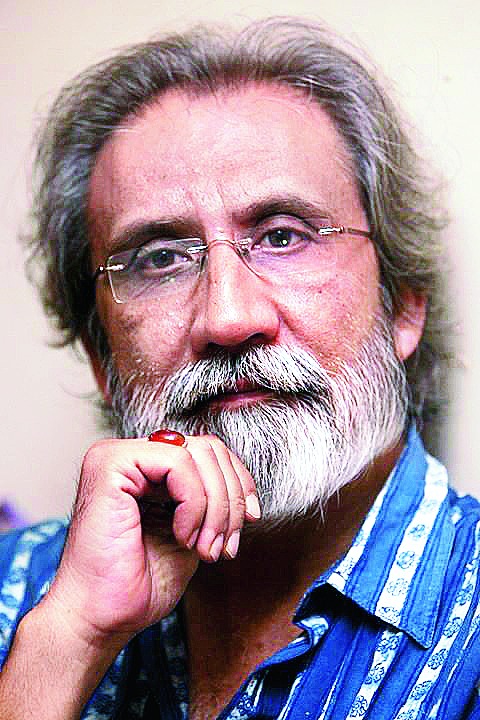

Habib is a Delhi-based historian and author