What was the last straw that broke the camel’s back, leading to the proclamation of an internal Emergency on the night of June 25, 1975? What were Indira Gandhi’s dark fears, and was the Emergency the result of a conspiracy against her? The Emergency has been looked at from every angle in all these years. The stage was set yet again this week on its 40th anniversary. Books, memorials, seminars, television studio discussions and opinion pieces in newspapers have been looking back at the 19 months of turmoil. But are we any closer to understanding the Emergency, which was like a stage full of characters in search of roles in a play without a plot? V. Kumara Swamy, Smitha Verma and Sonia Sarkar delve deep

THE GENESIS: There are two schools of thought on who was behind The Emergency. One section believes that Indira Gandhi - then Prime Minister - was advised by senior Congressmen such as Siddhartha Shankar Ray to order a clampdown on civil and other rights. Others are convinced that she was always a dictator.

Journalist Coomi Kapoor's new book The Emergency claims that the move was being planned from January 1975. Her book includes a hand-written letter by Ray, advising Indira Gandhi on January 8, 1975, to impose an internal Emergency. "Mrs Gandhi wanted to have a plan in place before imposing the Emergency. She struck when she thought she was ready," holds author-activist Kuldip Nayar, who was jailed during the Emergency.

But Gandhi's biographer Uma Vasudev holds that she didn't have "any totalitarian trait" in her. Socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan's call to the police and army to defy "illegal" orders was the last straw, she holds. "The system did not allow her to function. She had no other choice," Vasudev says.

And what did Indira Gandhi have to say? In an interview to The Daily Telegraph on September 25, 1976, she said: "We had not thought of the Emergency at all till the very last day. In fact, we worked all night or the day before," she said.

"Absolute nonsense," retorts B.N. Tandon, who was a joint secretary in the PMO's office then.

WHO DUN IT?

A handful of people knew what was happening. Gandhi's close circle included Ray, her economic adviser P.N. Dhar and confidant R.K. Dhawan. Dhawan, in recent interviews, says that Ray was the chief architect. From presenting the idea of the Emergency to drafting the proclamation that the President signed, he was at the centre of it all. The proclamation followed an Allahabad High Court judgment, declaring Gandhi's 1971 election null and void. On June 24, 1975, the Supreme Court gave a conditional stay on the high court order, but Gandhi clearly didn't want to wait for the final judgment.

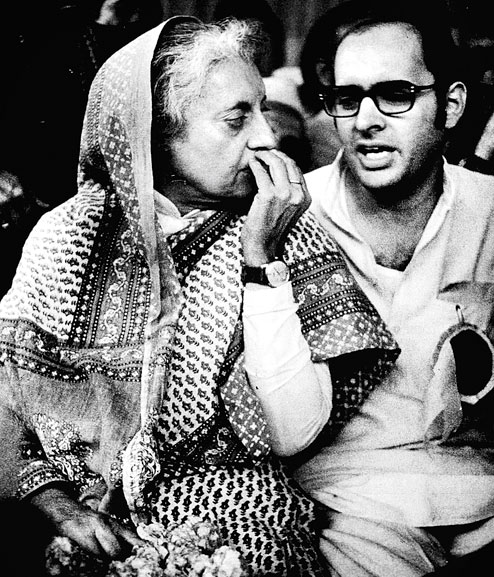

SON, SON, SON - HERE HE COMES

Gandhi's economic adviser Dhar quotes her as saying that before the Emergency, she did not have the power to implement the policies she thought India needed. "But when she did acquire all the power she needed, she did not know what to do with it," he writes in his book Indira Gandhi, The 'Emergency', and Indian Democracy.

Her younger son, Sanjay, had no such problems. Immediately after the proclamation of the Emergency, he put one of his cronies, V.C. Shukla, in place of I.K. Gujral as the information and broadcasting minister. Haryana chief minister Bansi Lal was brought back to Delhi as the defence minister. Operating from the Prime Minister's residence, he concentrated on implementing his "five-point programme" - a charter that included family planning, which he pursued with considerable zeal. Then there was his pet project - the Maruti car.

Vasudev recalls that during the Emergency, when she went to interview him, he took her for a drive. "He drove me around the factory campus in a Maruti 800 at the speed of 80 kilometres per hour. I was terrified. "So, does it run," he asked after a while. "Oh yes, it does," I smiled and said.

Old-timers believe that it was he - with his gang of friends - who wreaked havoc during the Emergency, with forced sterilisations, demolitions and acts of vendetta.

THE WOLF PACK

Sanjay Gandhi depended on a handful of people in and outside the government. Lal and Shukla were the trusted cronies. Bureaucrats Jagmohan and Navin Chawla helped implement his policies of family planning and beautifying the city. Young Congress workers such as Jagdish Tytler, Ambika Soni and old school chum Kamal Nath looked after the implementation of programmes and other activities. While Jagmohan went on to become a minister in BJP-led governments, Tytler, Soni and Nath have been ministers in Congress governments. Chawla became the chief election commissioner of India. Nath has been on a maun vrat on the issue ever since. Calls and messages to his office went unanswered.

A FEW GOOD MEN

Some didn't yield. Mohan Dharia, a freedom fighter and junior minister at the Centre, resigned and opposed the government in Parliament, calling the Emergency a "monstrous operation". Lawyer Nani Palkhivala, who had defended Gandhi in the Supreme Court after the Allahabad judgment, refused to represent her when the Emergency was imposed. Earlier this week, Fali S. Nariman wrote that he was the additional solicitor-general of India then, and quit the day after the proclamation. "Parsis, I must say, acquitted themselves well during the Emergency," Kapoor - herself a Parsi - says.

There was also K. Subrahmanyam, later hailed as one of India's foremost defence analysts. D.L. Sheth, honorary senior fellow and former director of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi, states that the IAS officer of the 1951 batch was transferred to Tamil Nadu in 1975 apparently for being opposed to the Emergency.

His son, historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam (another of his sons is the current foreign secretary), says that with other serving officers such as P.K. Dave and S. Guhan, he ensured that the Emergency was not used in an "abusive" fashion [in Tamil Nadu]. "This was appreciated even by those who were in prison (Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam members), as well as some figures who were allowed to pass through Chennai without interference. Questions were even raised in Parliament about why the Emergency was not being 'properly' applied in Tamil Nadu." After Gandhi returned to power in 1980, she sent Subrahmanyam to The Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, which he headed for long years.

MIDNIGHT KNOCKS

When the world slept, the Indian administration awoke - arresting the top Opposition leaders, led by JP, the night before The Emergency was declared.

"All those arrested on that fateful night from Delhi were brought to Parliament Street (police station) from where we despatched them by specially arranged transport to various temporary jails and designated circuit houses earmarked for each by the administration. As my memory goes, Morarji Desai and JP were sent to designated circuit houses in neighbouring states and not to any of the jails where most others were sent," recalls retired cop Maxwell Pereira, then sub-divisional police officer for the Parliament Street subdivision.

Socialist leader George Fernandes evaded arrest for over a year. He was holidaying with his family in Gopalpur in Orissa when he heard about the Emergency. Fernandes got ready to disappear. "I asked him, when do we meet again, he said, 'I don't know,' and left," says his wife, Leila Kabir. Fernandes was arrested almost a year later from a church in Calcutta. When Kabir wrote to Gandhi, asking about his whereabouts, she wrote back, saying, "Don't you know, he is a criminal?"

The police, however, could not lay their hands on the Jan Sangh member of Parliament Subramanian Swamy. He spent most of the time in disguise, in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, which were considered relatively safe. He even escaped to the US and led a propaganda drive against the government. He returned from the US and turned up in Parliament for a few minutes in August 1976, only to disappear again.

THE IRON LADY MELTS

Why did Indira Gandhi call off the Emergency? Again, there are two schools of thought. Because she had to, she told her adviser H.Y. Sharada Prasad. Because the Intelligence Bureau (IB) told her that she'd be back with a thumping majority, says Dhawan.

Prasad's son, Ravi Visvesvaraya Prasad, stresses that Gandhi told his father (who died in 2008) that she didn't believe in the IB reports. "The IB will tell me what I want to hear. I know I am going to lose but we have to go to the polls," Prasad quotes her as saying. Though the announcement (for the polls) came in January 1977, Gandhi had asked the chief election commissioner in 1976 to start preparing for them.

BUZZ IN TOWN

Candy is dandy, said the Emergency opponents, quoting Ogden Nash and referring to a would-be starlet said to be close to Shukla. The powerful minister - who got his hair cut at the salon at Delhi's Oberoi Hotel - was linked with many actresses of the era. The one who grabbed the headlines was "Candy" Vijay Kumari. He is said to have facilitated her admission to the Film and Television Training Institute, Pune. Zeenat Aman said Shukla had made "amorous demands" during a function in Bombay. After the Emergency was lifted, a magazine asked Shukla how he had acquired his "lecherous" reputation. "Maybe because I live well and dress well," he replied.

A story spread like wildfire about Sanjay slapping his mother. Lewis M. Simons of The Washington Post wrote that he slapped her at a private party before the Emergency. In 1977, BBC's David Frost asked Gandhi about the slapping incident. "If so, it's what my father would say, fantastic nonsense," she replied. "I have never been slapped by anybody in my life, so far. And he (Sanjay) has never slapped anybody."

And, of course, no Emergency story was complete without a reference to Rukhsana Sultana, a Delhi socialite who later gained fame as the mother of the actress, Amrita Singh. Sultana helped Sanjay implement family planning in Delhi's walled city. It is said that she'd even visited Tihar jail in Delhi where vasectomies were conducted on under-trials and convicts. "We used to hear a lot about her in jail," recalls Nayar.

Jagdish Tytler (who laughs when asked about Candy) stresses that Sanjay and Sultana were not in a relationship, a view also underlined by Vasudev. "One day, I went to interview her. She pretended that she'd got a call from Sanjay but it wasn't true. I discovered it when I went past her room to go to the washroom. It was funny," she says.

UNSOLVED MYSTERIES

Some Emergency-related stories are still being debated. Take the death of L.N. Mishra. The Union railway minister was severely injured in a bomb blast at a function in Bihar on January 2, 1975. There were allegations of corruption against him, and Gandhi was apparently unhappy with him. But the blast and his death troubled Gandhi deeply, says Tandon. Four people were sentenced after a 40-year trial last year, but it still remains a mystery. Were there others behind the murder?

Then what about the so-called CIA plot to get rid of Gandhi? Chilean leader Salvador Allende had been killed in 1973, and Ravi V. Prasad writes that she had been warned by Fidel Castro. Worries about an impending assassination were apparently also behind the reason for the clampdown. Was there any truth in that?

Forty years later, there is still talk of a "conspiracy" against Gandhi. Vir Sanghvi, in his book Mandate: Will of the People, writes that some - including Dhawan - believed so. "They believed that this conspiracy had been hatched by some of her closest advisors," Sanghvi writes. Dhawan thought Ray and a few others had an inkling of the Allahabad High Court judgment, and said so to Gandhi.

"The judgment was declared at 10am on 12 June, the first person to call on her was Siddhartha Shankar Ray. 'We have lost,' he told her. 'Yes,' said Mrs Gandhi. 'But you probably knew about it in advance," Sanghvi writes.

INDU, INDIRA, MUMMY, AUNT, MADAM

JP, who had supported Gandhi when she became Prime Minister, was close to her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, and addressed her as "Indu" in his letters to her. After talks between JP and Gandhi broke down, he addressed her as "Madam Prime Minister". Ray was the only Congressman then who called her Indira - as Sanghvi writes in his book. For Sanjay, Mummy was the front for his extra-constitutional powers. Arun Singh - later a minister in Rajiv Gandhi's council of ministers - wrote her a letter expressing concern a day after the Emergency was imposed. He addressed her as "Dear Aunt Indira". She replied a week later, signing off as Indira Gandhi. That was, of course, when she became Madam - and continued to be so till her death in 1984.

SOME FAMOUS LAST WORDS

Democracy is important but not more so than the country itself: Gandhi in a letter on July 5, 1975, to Arun Singh

Relief. Utter, utter relief: Gandhi, after being defeated in the 1977 elections, to David Frost in a BBC interview telecast on July 21, 1977

Indira Gandhi [has been] consigned to the dustbin of history: Atal Behari Vajpayee after he became the foreign minister in the Morarji Desai government

Epilogue

What happened to the dramatis personae after the Emergency

Indira Gandhi: Lost the 1977 elections and her Lok Sabha seat from Rae Bareli. Returned to power in 1980. Killed by her bodyguards in Delhi on October 31, 1984, in New Delhi

Sanjay Gandhi: Lost from Amethi in 1977. Died when a Pitts S-2 plane he was piloting crashed on June 23, 1980

S.S. Ray: He went on to become the Governor of Punjab in the late 1980s and was also India’s ambassador to the US from 1992 to 1996. He died in Calcutta in 2010, at the age of 90

Jayaprakash Narayan: Cobbled together the Janata Party just before the 1977 elections. The party won, but he stayed away from electoral politics. He died on October 8, 1979, aged 77

L.K. Advani: Served as the minister of information and broadcasting under Morarji Desai after the Janata Party came to power. He was among those who founded the BJP, and then rose to become the deputy prime minister under Atal Behari Vajpayee. A member of Parliament, he is largely seen as a leader with no role

Arun Jaitely: Active during the Emergency as a student leader, he studied law and rose as a lawyer. He is now the Union minister of finance

George Fernandes: Won the 1977 elections from Muzaffarpur in Bihar. Went on to become the industries minister in the Desai government, and later supported the BJP. He was India’s defence minister in the Vajpayee government in 2001-04. A patient of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, he now lives with his wife, Leila Kabir, in Delhi

Subramanian Swamy: Won the Lok Sabha election from Mumbai North East in 1977. Was Union minister of commerce and industry in 1990-91. Merged his Janata Party with the BJP in 2013

Sanjay’s circle: V.C. Shukla changed parties frequently, but returned to the Congress. He died after a Naxalite attack in Chhattisgarh in 2013; Bansi Lal formed the Haryana Vikas Party in 1996. He died in 2006; Jagdish Tytler came under a cloud during the 1984 anti-Sikh riots; Ambika Soni is an active member of the Congress, close to party president Sonia Gandhi; Kamal Nath has remained with the Congress and held several portfolios. And is still silent.