It's a topic that he can hold forth on for hours on end. The monsoon, for meteorologist Madhavan Nair Rajeevan, is not just a passion - but a matter of scientific curiosity.

That's not really surprising for Rajeevan has spent nearly three decades studying the intriguing weather system that, for thousands of years, has been bringing bountiful rains - and an occasional drought - to India and other countries in the subcontinent.

But it's a bit ironical that we are discussing rains in the midst of a scorching heat wave which has been killing hundreds of people in different parts of the country. There's hope, though, for weathermen have predicted that clouds bearing the monsoon rains are just around the corner and may make a landfall in Kerala on or before the appointed date of June 1.

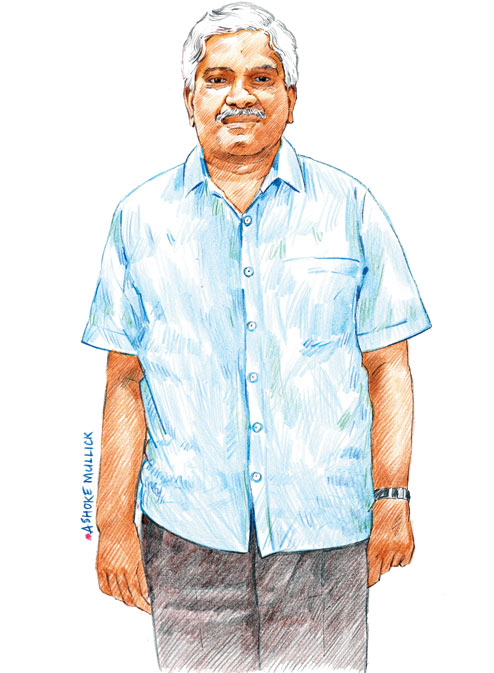

"We still do have not a clear understanding of many phenomena that influence the monsoon," says Rajeevan, who recently took charge as the director of the Pune-based Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), a part of the Union ministry of earth sciences. The IITM, whose founder-director was the renowned Indian meteorologist P.R. Pisharoty, is a vital cog in the country's efforts to improve its ability to forecast the southwest monsoon, which accounts for nearly 75 per cent of annual rainfall received in the country.

The 53-year-old scientist, who belongs to a village on the Kerala-Tamil Nadu border, not very far from the spot where the monsoon is first sighted and felt every year, is not sure when he first fell in love with the mysterious phenomenon of the monsoon. But it became an integral part of his professional life when he joined the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the official weather forecaster of the country, in 1985. For nearly 15 years, he headed the IMD's long-range forecasting division in Pune.

Now, as the head of IITM, Rajeevan is spearheading a national mission to improve monsoon forecasting. In 2012, India announced a Rs 400-crore National Monsoon Mission, with Rajeevan as its programme director.

The five-year-long mission seeks to improve monsoon forecasting models. "The idea is to have a model which can give different ranges of weather forecast,"says Rajeevan in his deep baritone.

Officially, India issues three types of rainfall forecasts, and is contemplating a fourth. There is a short range forecast (up to 3 days), medium range (up to 10 days) and a long-range forecast, which is normally done for the entire monsoon season of four months.

"The long-range forecast is of no use to farmers," explains Rajeevan. "But if we could tell them what they can expect, say, over the next 15-20 days, they can plan their sowing, irrigation and water storage accordingly. This is what is called extended range forecasting," he adds.

Unfortunately, the weather forecasting models that India currently employs are actually not capable of offering such forecasts - which is something that the monsoon mission plans to come up with.

Rajeevan's colleagues at IITM believe that his rich experience in long-range forecasting can give a boost to efforts to develop a new model for forecasting. "He actually knows the issues first hand, being a forecaster himself," a colleague stresses, though Rajeevan underlines the collective nature of the mission and holds that a lot of work had been done at the institute much before he had joined as director.

The monsoon, however, is not an easy field of study. Of late, things haven't been going well on the monsoon-forecasting front. The mismatch between what is forecast and the actual quantum of rainfall has been apparent over many years in the recent past. Critics say the IMD got its annual monsoon prediction right only 12 or 13 times in the last 25 years.

That's a pity. An accurate monsoon forecast can offer rich dividends. In good monsoon years, it can help the country tap favourable conditions to post a robust growth, while advanced warning about a bad spell can prepare it accordingly.

"The long-range monsoon forecast has become a tricky job of late," Rajeevan observes as we settle down for a conversation in his spacious Pune office, whose size is further accentuated by the fact that it's largely empty. The walls are still bare and cupboards look empty, indicating that its new occupant has just moved in.

<,>S<,>tocky, well-built with greying hair, Rajeevan, however, seems to have segued into his new job well. "I have been closely interacting with IITM scientists much before I moved in here," Rajeevan, in a blue shirt and dark trousers, points out.

The scientist has returned to the city after a gap of seven years. In 2008, when he was heading the IMD's long-range forecasting division in Pune, he joined the Indian Space Research Organisation's National Atmospheric Research Laboratory near Tirupati. "The three years I spent with NARL helped hone my skills in observational data collection," says Rajeevan, who subsequently moved to the earth ministry headquarters in Delhi.

With a master's degree in physics from Madurai Kamaraj University, Rajeevan first joined the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research as a senior scientific assistant in 1983. Two years later he joined the IMD as a meteorologist after a year of training.

India uses what meteorologists call a statistical model to forecast the expected quantum of rainfall for a monsoon season. This model uses certain indicators from the pre-monsoon season that yield an equation leading to a forecast which is expected to be close to accurate. But that is not always the case.

"It is not that these statistical models are bad. But they suffer from certain constraints," Rajeevan elaborates. These models, he says, cannot take into account what researchers call feedback processes. Feedback processes are those changes - such as sudden disturbances - that influence the final outcome.

Rajeevan gives the example of El Niño, an unusual warming in the Pacific Ocean, which influences the Indian monsoon, though it occurs thousands of kilometres away from the Indian landmass.

"Suppose we have taken 0.5 degree Celsius as three-month average temperature increase in the specific El Niño region. Based on this, we run the model and give a forecast. Later on, if the temperature differential increases to, say, 0.6 degrees Celsius, there is no way we can go back and get a new forecast," he points out. "Statistical models are also very static in nature," he laughs.

Dynamical models, which require a higher level of number crunching and deeper understanding of the science involved, on the other hand, offer flexibility. What is more, they can be tweaked to give forecasts for whatever intervals are desired, for instance on a monthly or fortnightly basis.

<,>T<,>he Monsoon Mission could probably be a game changer. As part of the mission, India has already adopted a dynamic model developed by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (US) for monsoon forecasting.

"The experience with this model in the last two years has given us some hope. Forecasting the extended range is supposed to be a difficult proposition, but the results we have got so far are really encouraging."

Rajeevan, who is the son of a farmer, however, says that a lot more has to be done before the model can become operational and be handed to the IMD for regular forecasts. "We still do have not a clear understanding of many phenomena that influence the monsoon. Unravelling the physics behind them is the key to developing a better forecasting model. As many as 30 projects involving scientists from different Indian institutions as well as abroad have been sanctioned keeping this in mind."

For the mission, the IITM has installed India's most powerful supercomputer on its campus at a cost Rs 125 crore.

"The monsoon has always been an enigma for scientists all over the world," Rajeevan says. That as many as 20 scientific groups from abroad have undertaken projects as part of the mission itself indicates the international interest in the rain system.

One of the joint projects will be studying the tropical monsoon clouds, which are very different from those found in other parts of the world. "During this monsoon season, a research aircraft, specially designed to go into the clouds and study different parameters, will be engaged," he says.

Similarly, an IITM team has just set up an observatory that can analyse clouds in Mahabaleshwar, which is 1,500 metres above sea level. "Clouds that are formed in the valley in the monsoon will pass through this observatory, giving us an opportunity to study them," he adds.

In July, researchers from the US and India will be aboard a research ship in the Bay of Bengal. "We know very little about how the mixing of freshwater (from two of India's biggest rivers - the Ganga and Brahmaputra) with sea water in the Bay Bengal influences the monsoon," he says.

Once the studies yield results, and if everything falls into place, India will have a much reliable monsoon forecasting model by 2017, he says. And what's two years in a weather phenomenon that has been around for thousands of years?