The ‘hack’ who came in from the cold

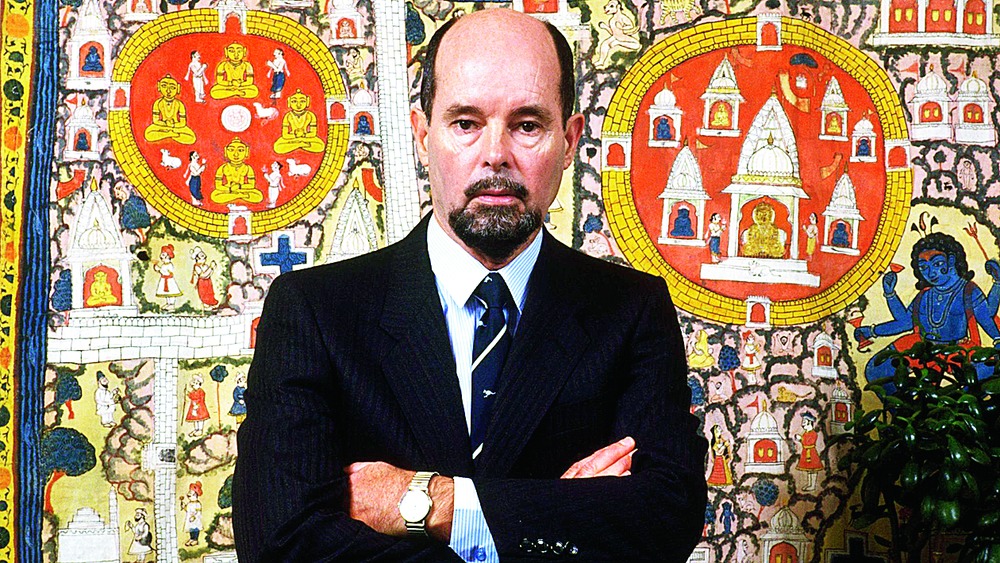

As a tribute to the investigative journalist, Phillip Knightley, who has died in London, aged 87, I have been rereading his self-deprecating memoirs, A Hack’s Progress, in which he writes engagingly of his time in the cosmopolitan Bombay of old, when he was managing editor of Imprint and later discovered the magazine was CIA-funded.

I have also been looking for the copy I know I have of perhaps his best known book, The First Casualty: From the Crimea to Vietnam: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist, and Myth Maker.

Phillip is survived by his wife, Yvonne (née Fernandes), a Goan girl he met in Bombay and married in London in 1964 when — after an indifferent early career in his native Australia — he joined The Sunday Times and broke many world exclusives under its legendary editor, Harold Evans.

Those were halcyon days when reporters could spend months following a lead and espouse “the long form of journalism” — Phillip once wrote a piece 12,000 words in length (in contrast, my first “focus” on an Oxford tragedy when I joined the paper nearly three decades later was 2,200 words, an indulgence by today’s standards).

Phillip, an expert on espionage, spent 20 years developing a relationship with the British spy, Kim Philby, interviewed him in Moscow, and wrote a bestseller, Philby, KGB Masterspy.

Phillip also leaves behind daughters Aliya and Marisa, son Kim, and four grandchildren.

A charming, understated man, he will be greatly missed by his many friends in India, among them fellow journalist Rahul Singh. They shared a love of tennis (often at the Bombay Gymkhana) and fresh “lobster and prawn”, especially in Goa where the Knightleys had a home. In India, Phillip learnt the value of a 15-minute nap after lunch.

Rahul told me last week just how easygoing Phillip was.

“He was one of the few people who tolerated Sasthi Brata,” joked Rahul, recalling the mercurial Indian author of My God Died Young. “Phillip’s Notting Hill home was open house for all visitors.”

Marking Modi

All of a sudden, Narendra Modi seems to be getting a terrible press in Britain, especially on the BBC.

First, BBC Radio 4’s The World Tonight interviewed Amartya Sen, who rubbished demonetisation as “despotic” and claimed it could harm economic growth.

Then we had a radio report on Hindu fanatics hunting at night for cattle-bearing lorries, followed by a despatch by the BBC’s South Asia editor, Jill McGivering, on how RSS groups were targeting minority communities in Indore.

She spoke to one Shahid Mohammed Khan, a newspaper and bookseller for 40 years, who was thrown into police lock-up for three days because the content of one paper he sold had offended someone.

“We are frightened now,” Shahid told the BBC.

The Madhya Pradesh state government spokesman, Hitesh Bajpai, dismissed all criticism as “political reaction” and said everyone was living harmoniously. But McGivering, an old India hand, appeared unconvinced.

Night vision

The BBC spent £20 million filming in 40 countries over five years for its latest six-part natural history series, Planet Earth, but the Indian sequences are by far the most dramatic.

In particular, night vision cameras captured heart-stopping, black-and-white footage of a leopard pouncing on a mother pig in a Mumbai bustee and making off with one of her squealing piglets. The cruel but stunning scene (during which the cameraman was himself vulnerable to the leopard) shocked millions of British viewers last week.

Special cameras travelling on what looked like clothes lines caught langurs in full flight between buildings in Jodhpur.

Presenter Sir David Attenborough, 90, explained: “Leopards have attacked almost 200 people here in the last 25 years. But these leopards are on the hunt for something else — pigs. The ceaseless noise of the city conceals their approach…”

Producer Fredi Devas added that Indian people are “totally remarkable in their tolerance” of allowing even leopards into their city. “The relationship between animal and man — the acceptance, the tolerance, the compassion and just their ability to share a city with each other — made it stand out as a place that was completely inspiring.”

Pakistani wars

A Pakistan family is at war Hindi TV serial-style — unfortunately it is that of boxing hero Amir Khan, 30, whose wife, Faryal Makhdoom Khan, 25, a former model, has been slammed by her husband’s ultra-orthodox parents, Sajjad and Falak, for dressing in an “un-Islamic manner”. Her brother-in-law, Haroon, has accused Faryal of resembling Michael Jackson after cosmetic surgery.

Faryal has hit back by going on television and posting a picture of Haroon lying naked and apparently drunk.

Caught between his parents and his wife, Amir’s three-year marriage is said to be headed for divorce, say embarrassed Pakistani journalists.

Meanwhile, British tabloids and TV are finding the unseemly squabble richly entertaining.

Far-sighted

What will India look like 2,000 years from now? I ask because the “Goethe-Institut London and the Victoria and Albert Museum have commissioned 12 artists from around the world to imagine what Europe might look like 2,000 years from now, and how our present might be viewed from the future”.

Great credit then to London-based art college lecturer Jasleen Kaur, born in Scotland of Punjabi parents from India, and the Raqs Media Collective from Delhi (whose intriguing colonial statues I saw at the Venice Biennale last year) who are among the dozen.

Jasleen, who is making a video, says: “My pseudo-documentary provokes questions around whose voice history is written in.

“With Shah Rukh Khan as the default protagonist a future is proposed where the West’s history is written by the East,” the artist tells me.

Tittle tattle

London is looking exceptionally pretty with all the Christmas decorations. Among the stores, Fortnum and Mason is a treat.

But causing misery for millions are strikes on Southern Region, where a crazy management wants to introduce trains without guards on platforms and remove all staff from ticket offices. Plus, there is the seasonable walkout by post

office workers.