|

|

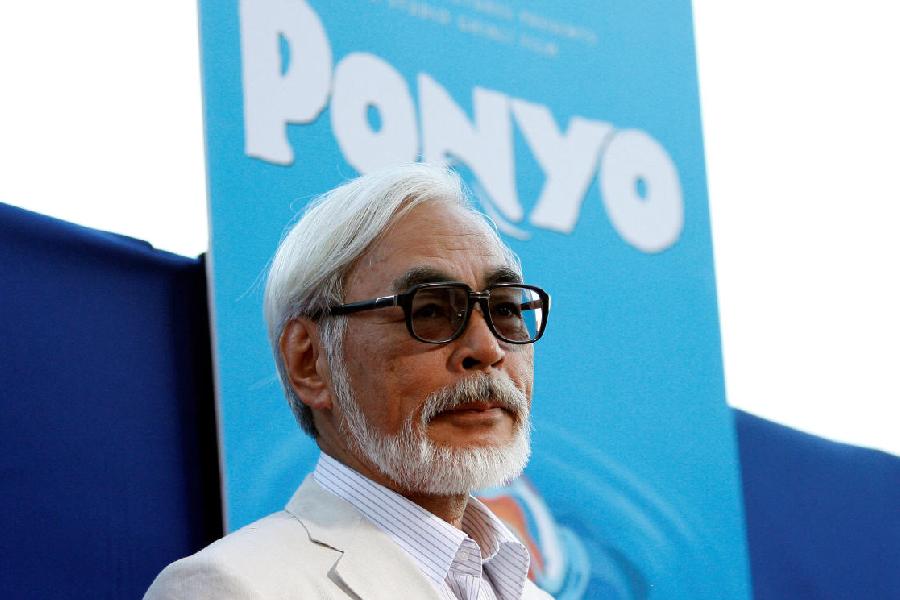

| REAP HEAP: A farmer in Cuttack district who grew BGREI rice last year. Picture by Debaashish Bhattacharya |

Rain buffets him in all its fury. But Aniruddha Mohanty sits unmoved in a corner of a sodden rice field, sowing the seeds of paddy — and of a Green Revolution. The wiry, middle-aged man from Kherasa village in Odisha’s Cuttack district is among a band of farmers roped in across eastern India to experiment with what’s being called scientific farming in India’s most ambitious agriculture project since the 1968 Green Revolution.

“The life of a farmer is going to change for ever,” says Mohanty.

BGREI (bringing Green Revolution in eastern India), unveiled barely two years ago by the Union agriculture ministry, aims to turn agriculturally laggard regions into a food-surplus zone. It is being implemented in seven states, with an outlay that jumped from Rs 400 crore in 2010 to Rs 1,000 crore in 2012.

The new project proposes a chain of measures to raise productivity without setting any specific targets. It also proposes building agricultural infrastructure in Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Assam, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and eastern Uttar Pradesh, where the project has been underway.

A key BGREI component is the creation of demonstration centres of 1,000 hectares each in selected blocks by getting the farmers to share their land and give modern farming a go.

If the first Green Revolution was largely about increasing wheat produce in north India, the second revolves around rice production, even though wheat and pulses have also been included in the programme. What’s driving BGREI is an aggressive use of micro nutrients and hybrid paddy seeds being used in the demonstration centres to raise productivity.

Clearly, India needs to jack up its food production to feed its ballooning population. But that may prove difficult unless Indian farmers give up their age-old tilling practices in favour of modern-day farming.

“The only way to ensure food security, a concern of every Indian, is to grow enough foodgrains domestically,” says Union agriculture ministry joint secretary (crops) Mukesh Khullar, the BGREI programme director.

The programme is indeed vital to the nation’s food security. India imported nearly 6.5 million tonnes of wheat to meet a domestic shortfall in 2006-2007. It continues to import foodgrains every now and then to meet domestic demand.

No wonder the project, a special initiative of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, found an emphatic mention in this year’s budget speech of finance minister-turned-presidential candidate Pranab Mukherjee.

|

BGREI is equally important to the farmers. “The project is necessary to ensure the livelihood security of nearly 70 per cent of the rural population that depends on crops and animal husbandry,” says agriculture scientist M.S. Swaminathan, credited with the success of the Green Revolution. Agriculture in India is “as much a livelihood enhancement enterprise as a food production one”, he says.

Indeed, Abhiram Parida, a 58-year-old farmer of Odisha’s Dhanamandal village, hopes more production will translate into more money saved. He wants to put his two sons through college and marry off his daughter to a man with a steady income.

Last season, he harvested 80 quintals of paddy from his one-hectare plot — 30 quintals more than his usual annual yield. But he had to sell it at Rs 750 per quintal even though the government procurement price was Rs 1,080 per quintal. “There were no takers. So I had to finally sell it to middlemen who took full advantage of the lack of an open market for paddy,” the farmer rues. But he hopes that with BGREI, the paddy procurement system will change over time.

It’s not easy to nudge farmers, who have for generations worked the land in an almost unchanged fashion, to change.

Mohanty, for instance, wasn’t convinced to begin with. Like most of his fellow farmers in Kantapada block who had helped build a 2,000-hectare demonstration centre with their land, Mohanty says he was sceptical about the efficacy of scientific farming. But district agriculture officials brought him around and Mohanty says he is now inspired by the results.

“I got 70 quintals of paddy from one hectare of land last year versus 45 quintals in the previous year,” says the beaming Odisha farmer.

The effort is beginning to pay off. Most of the seven states have reported at least a 15 per cent jump in rice production in the blocks where the project was implemented last year.

“We achieved a 15 to 20 per cent growth in paddy in the kharif season and a nearly 25 per cent growth in the bodo season last year in areas under BGREI,” says Bengal principal secretary (agriculture) Hirdyesh Mohan. “This is a major success.”

Evidently, eastern India — once depicted by the National Commission on Farmers as the “sleeping giant” of Indian agriculture — has a vast untapped potential. It, for one, has plenty of water, the mainstay of Indian agriculture.

“Water management is the main problem in eastern India, not water availability,” says Swaminathan. The east was selected for the project essentially to harness the region’s “abundant water resources”, necessary to enhance the production of foodgrains, adds Khullar.

Though the seven governments are implementing BGREI in their respective states, the Union agriculture ministry is providing “certified” or better quality hybrid seeds to help enhance production. Farmers are clearly excited.

“Getting the right seeds on time is always a problem. But we were given free certified seeds in June last year just when we needed to sow them,” says farmer Alauddin Mondal of Rajballavpur in Bengal’s North 24 Parganas district. Mondal usually relied on cheap “local seeds” that hardly helped raise production.

Like other farmers from the Habra block, Mondal says he followed the BGREI guidelines carefully during cultivation, using micro nutrients such as zinc. He ended up with eight bags of paddy — each bag containing 60 kilos — from his land against the normal yields of six bags.

The right seeds and right micro nutrients have helped other farmers as well. “I just could not believe it. I usually get 40 bags of paddy from my five bighas of land. But this time, I got 55 bags,” says Ratan Chakraborty of Salka village in Habra.

The scheme is also expected to correct some of the wrongs of the Green Revolution. The Sixties’ movement — which saw the use of high-yielding, genetically-modified seeds — lifted the country out of an “agricultural dark age”, experts say, but it had many pitfalls too.

Experts point out that BGREI was drawn up to reduce pressure on Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh — regions that have been feeding the people for long. The over-exploitation of groundwater for irrigation left the three states virtually depleted in terms of water resources, a major concern of the country’s agriculture planners.

Further, the heavy use of chemicals, especially pesticides, damaged the soil and ecology of northern and western India, adversely affecting the health of people and livestock, points out Jagadish Pradhan, a former member of the National Commission on Farmers.

To top it, the “overproduced” wheat from the northern regions had to be transported to non-wheat consuming areas such as Bengal, Odisha, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, changing the food habits of locals and affecting their health.

“Tribals were the worst affected since they went for wheat not produced by them instead of millet which they produced and which was far more nutritious,” Pradhan stresses. “But there is also no denying that the Green Revolution was an absolute necessity for India when it took place in the 1960s.”

The BGREI seeks to plug some of the loopholes of the earlier revolution — especially by reaching out to areas in the east.

Already, buoyed by the success of the scheme so far, most of the seven states are expanding the cultivation areas under BGREI. Bengal, for instance, had 67,000 hectares in 16 districts under the project last year. “But this year, we are covering nearly 2,00,000 hectares,” says principal secretary Mohan.

The other states have a similar story to relate. “This project is an unqualified success as of now. We plan to bring the entire state under BGREI in the current financial year,” says Odisha principal secretary (agriculture) R.L. Jamuda.

Odisha had 52,000 hectares across 15 of its 30 districts under BGREI in 2011. It’s now set to expand to 1,55,000 hectares this year. The state has reported a 20 per cent average hike in food production in the areas where the project was implemented last year.

Interestingly, Bengal is also trying to push up its wheat production under BGREI, especially in Murshidabad, Birbhum and Malda districts. “We had a 20 per cent increase in wheat production in these areas under BGREI,” Mohan says.

The state is also setting up procurement centres, weigh bridges and kisan mandis in all 341 blocks by way of “asset building”, as envisaged in the project.

All this costs money. Fuelling the project is the Centre’s generous funding. In fact, some experts ascribe the programme’s initial success to nothing more than cash. “This programme is a tremendous success primarily because important components such as certified seeds and micro nutrients are being used generously. We could not do this earlier because we had a funds crunch,” says agriculture expert Subir Choudhury, a consultant to Bengal’s agriculture department.

Needless to say, the total BGREI allocations for the seven states have leaped two and a half times in the last two years. If Bengal got Rs 102.37 crore in 2010-2011, it received Rs 269 crore for 2012-2013. Odisha’s allocations have similarly gone up from Rs 79.67 crore to Rs 217.25 crore in the last two years.

Bihar will get Rs 119.25 crore this year, up from the Rs 63.94 crore it received two years ago. Assam and Jharkhand will get Rs 95.50 crore and Rs 59 crore, respectively, this year against the Rs 17.50 crore and Rs 14.80 crore of 2010-2011. The figures for Chhattisgarh and eastern Uttar Pradesh, too, have gone up from Rs 67.15 crore and Rs 57.27 crore to Rs 131.50 crore and 105.50 crore, respectively.

So far, so good. But not everyone is impressed.

Swaminathan calls the government approach to the second Green Revolution “technocratic”, with the sole emphasis on hybrid rice. “The other aspects, particularly water management, assured irrigation and soil health management are not receiving the same attention,” he stresses.

A Bihar official says though the project seems to be taking off, concerns such as irrigation and a remunerative support price for paddy persist. Farmers, too, say they worry more about selling their paddy without any loss than about raising their production.

“Where is the incentive to grow paddy in the first place? We have no open market to sell it,” says Suhas Das of Simulpur village in Bengal. He says rice growers like him have had to sell a 60kg bag of paddy for only Rs 700-750 to rice mill agents, incurring a loss of at least Rs 200.

|

Odisha farmers complain of the labour force disappearing from the villages, thanks to the boom in construction in urban areas and a spurt of rural projects under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. “Farm hands are hard to get. They’ve also become very expensive,” says Niranjan Pradhan of Dhanamandal village in Cuttack district.

There is also storage problem, with fewer mandis available. Coastal Odisha doesn’t have enough rice mills despite being called the state’s rice bowl.

R.S. Gopalan, director, agriculture department, Odisha, says farmers are also not very keen on hybrid paddy since the hybrid seeds cannot be used for a second year.

True, Indian agriculture relies on many factors, including the monsoon, and the project’s proponents stress that it is not possible to put everything right under one scheme. But they insist that a start has been made and it is now for the seven states to take the project forward.

Encouraged by the “positive impact” the project has had on the seven states, the agriculture ministry is now thinking of bringing six other northeastern states under BGREI. Khullar stresses that the project has “no time limit” and there is little chance that the funds will dry up anytime soon.

Even if the project were to wind up in the future, few officials see the farmers going back to their old ways because of the way they have been “sensitised”, as Guruprasad Tripathy, deputy director of the Bhubaneswar-based Institute on Management of Agriculture Extension, puts it.

“There is no going back now that we know what leads to more yields. I am going to use zinc and certified seeds for the rest of my life, whether the government provides them or not,” says farmer Suranjan Sarkar of Raghavpur in Bengal.

The ultimate success of India’s second Green Revolution is riding on that.