|

|

| Write stuff: Mohsin Hamid |

|

| Daniyal Mueenuddin |

|

| Kamila Shamsie |

|

| Mohammed Hanif |

At the mid-town Manhattan offices of William Morris Agency, adrenalin levels were running high. Messages were flying in thick and fast, the phones were ringing, Blackberries were on overdrive, the decafs were flowing and all eyes were watching in nervous anticipation as the auction progressed.

The man causing the flutter was a young Pakistani writer, lawyer and sometime farmer Daniyal Mueenuddin, whose collection of short stories In Other Rooms, Other Worlds had led to unprecedented interest from 10 US publishing houses at the September 26 auction. Many of the stories had been previously published in The New Yorker. Among the bidders were editors from Random House, Riverhead, Knopf and Norton. Within hours, the price crossed the magic six-figure line and finally it was Norton that carried the day.

Five days later, the setting was London and the Soho offices of William Morris. Once again, three major publishing houses were interested in Mueenuddin’s work. The deal went to Bloomsbury for a five-figure sum. In India, the deal was secured by Random House India, which pre-empted the other publishers and signed the writer who has been described as the equivalent of Ivan Turgenev and William Faulkner.

The buzz created by Mueenuddin is part of a wider picture, as young Pakistani writers in the West make their mark on the global literary landscape. “The western world is fascinated by Indian and Pakistani culture,” says Cathryn Summerhayes, Mueenuddin’s literary agent. “There is more than an obvious release of energy from Pakistan. Our phone was red hot with the interest from publishers.”

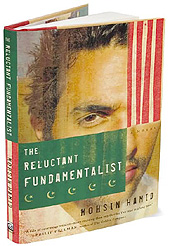

Weeks before the auction, the nomination of Mohsin Hamid for this year’s Booker Prize had put Pakistani writers firmly in focus. If Hamid carries off the £50,000 prize on October 16 for his The Reluctant Fundamentalist, it will do for Pakistani writers what Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children did for Indian writers in the Eighties, and the renewed interest in Indian writers that Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things sparked in the Nineties.

Hamid has already sold over 12,500 copies since the Booker nomination. The novel — set in a café in Lahore’s Anarkali Bazar where Changez, a young US-returned Pakistani, converses with an American stranger — has been described by last year’s Booker winner Kiran Desai as “a brilliant book that unpicks the underpinnings of the most recent episode of distrust between East and West.”

The interest in Pakistani writers coincides with the global attention on events in Pakistan. The trend, Pakistani writer Kamila Shamsie holds, has been visible for some years now. “This year the Booker nomination has put it in focus,” says the author of the critically acclaimed Salt and Saffron and Broken Verses. “My first book was published in 1998, Mohsin Hamid published Moth Smoke in 2000, Moni Mohsin (The End of Innocence) was published last year by Penguin. The trend has been happening from around the turn of the millennium.”

Pakistan, Shasmie points out, is in the news. “There is a lot of interest in the country and the new writers emerging from it,” she says. “Also, more people are writing now. At the time when I began writing, most people would say I was wasting my time. But writing is no longer something that seems like a ridiculous idea in Pakistan. It needs the success of a few writers to fuel others.”

Her thoughts are echoed by Mohammed Hanif, head of the British Broadcasting Corporation’s Urdu service, whose novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes is due for publication in May 2008 by Random House in the US, Jonathan Cape in the UK and by Random House India. The former Pakistan Air Force officer’s novel, set in the last years of General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime in Pakistan, gives a fictional account of what happened to the Hercules C130 — the world’s sturdiest plane — which crashed on August 17, 1988, killing the Pakistani President, and examines a number of conspiracy theories about his death.

“It was lazy journalism,” laughs Hanif. “There were always so many theories (about Zia’s death) that I thought I would put them down and fictionalise the story.”

Hanif was taken on by sought-after agents Clare Alexander and Gillon Aitken (formerly Rushdie’s agent) and soon had publishers bidding for his debut novel on both sides of the Atlantic.

“I hope this interest is happening for the right reasons. I think people want to hear stories from that part of the world, and publishers get interested,” he says.

Chiki Sarkar, chief editor, Random House India, definitely thinks so. In London to secure the deal with Mueenuddin, she says that the fiction that has most struck her over the last few years has been Pakistani.

“There’s a blackness, political engagement and relevance in the writing of young Pakistanis that I love and find as a publisher incredibly exciting,” says Sarkar. “Mohsin Hamid’s Moth Smoke was to my mind the most interesting novel that came out of my generation of subcontinent writing, and his second book has followed up on that promise.”

She describes Hanif’s writing as “gritty and cynical”, words she says she will not use to describe much of Indian fiction. Writers such as Mueenuddin, she feels, are like the R.K. Narayans of Pakistan, writing about feudal Pakistan — of cooks having love affairs with the maid, of masters and servants — “a world that in the English language has never been brought alive till now.”

The writers are not just limited to fiction either. Greetings From Bury Park by Sarfraz Manzoor, a television presenter and Guardian columnist, recalling his childhood in a working class neighbourhood in Luton, has won critical acclaim. He agrees that some of the interest in Pakistani writers has happened because of the new-found interest in Islam, fundamentalism and therefore the market for interesting stories from these communities. His own book, he feels, was bringing a personal story about a Pakistani family in a way not written about before.

“I would hesitate, however, to describe it as a trend,” says Manzoor. “I think there are a lot of writers around. They are writing different things and they have different styles.”

Similarly Ed Husain’s critically acclaimed The Islamist which documented the author’s days as a member of the fundamentalist Islamic organisation, Hizb-ul-Tahir, in Britain and his eventual disillusionment with it, is evidence that the West wants a look-in on a world it is just discovering. Novels from Afghanistan, such as Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner, have drawn an audience in a world intrigued by the Taliban. Tales from Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad, with a heady cocktail of generals, mullahs, feudalism and fundamentalism, are attracting readers like never before.

While Hanif Kureishi, Tariq Ali and Bapsi Sidhwa were the only names associated at one time with Pakistani writing, the list has now become seamless. The reason may go beyond what Mohsin Hamid describes as the “fast-bowler” effect: the reason Pakistan produced a string of fast bowlers was because they all wanted to emulate Imran Khan and his success. Today’s writers have found their own voice: novels, short stories or memoirs, they are doing it their way. The new kids on the block have arrived and the chances are there will be many more.