|

Zahan ke peechey kisi aur satah pe kahin

Jaise chupchap barasta hai tassavur tera

(Jhari)

In the depth of my thoughts, at another level somewhere

I think of you like the rain, falling silently

(Drizzle)

At the Frankfurt book fair a year ago when India held the spotlight, a poet met an author and discussed a common favourite: Mirza Ghalib.

Gulzar had written a biography and made an eponymous television series on the 19th century poet. Pavan Kumar Varma, career diplomat, had also written a well received biography of Ghalib and was eager to translate Gulzar’s poems. So Selected Poems came into print — a collection mined from previous works, mainly Raat Pashmine Ki and Pukhraj, reflecting Varma’s choice.

“Pavanji has chosen words along with its fragrances and shadows. So that is why I feel my poems are a little different,” Gulzar says.

“Along with the thought, it is the expression or the imagery that comes right from our everyday living which is a little unusual, I would say. And after all these years, I can take that much liberty with myself, to say it. And very modestly I wish to express this,” Gulzar says, his chuckles and throaty laughter erupting frequently.

The word charmer can bend letters to his will. The director of masterpieces such as Mere Apne, Angoor, Aandhi and Maachis is on hiatus for the moment. The lyricist of Omkara and Bunty aur Babli — including chartbusters Chhaiyan Chhaiyan, Kajra Re and Beedi Jalaile — is deferring to the poet for now.

Gulzar writes in Urdu, a spiral notebook filled with verses in black ink, with some sketches to fill the pause that comes as image transforms into words. He has doodled a tiny cartoon of a mother and child sparring. It’s cute isn’t it, chuckles Gulzar. Those notebooks are collector’s items, I say, coveting a leaf for myself. He laughs even more.

“It’s because of the script, not because of the writing. I write in Urdu which is so rare today. People write mostly in Devnagari. But this was my first medium from school. I love this language. In Jhelum (now in Pakistan) and later in Delhi where I grew up, I kept my first medium of writing Urdu,” he says.

The poet writes in his notebook, closes it, gets it out of his system and then revisits it — a month or a year later. He is constantly revising and chiselling his words and “sometimes even spoiling them.”

His search, he says, is like an attempt to express the vacuum that exists between the last day of college and the next day of stepping into something new. “I try to express that line,” says this winner of the Sahitya Akademi award and the Padma Bhushan.

Gulzar sits in his Mumbai home across the sturdy book-stacked table in his study shielded by a chik curtain. From a wall, a young Meghna aka Bosky stares out of a striking black and white picture taken by her father. Gulzar dedicated Selected Poems, released earlier this year, to Meghna, her husband Govind and Pluto, the erstwhile planet that was demoted.

Dressed in, what else but, trademark white kurta-pyjamas, the imprint of Gulzar’s 74 years is as invisible in his charismatic appearance as in his contemporaneous lyrics. How many sets of white KPs does he own?

“Two. I wash one and wear one.” I almost believe him, till he tells another story. “This is what my daughter had asked me when she was very young. She said, ‘Papa, why don’t you wear anything else?’ I said, ‘I don’t have anything.’” So how many kurtas do you have? “Two. And my little innocent girl told her friends, ‘my father has only two kurtas. He wears one and washes the other’,” he recalls, amusement warming his voice. For the record, in cold climes he trades his pyjamas for white woollen trousers, but the kurta remains. And the tally stays a secret.

Along with couturiers, he also denies cell phone companies any business. He doesn’t like keeping a mobile phone, although music maestro A.R. Rahman once gave him one. “Shah Rukh (Khan) just asked me, ‘so you are the only person in the world who does not have a cell phone?’ I am sure he must have come to know because he was working with Rahman, but that’s how it is,” he twinkles.

Weaving between different genres presents no conflict to this poet.

Film writing is not a tussle — he has prepared for it for 40 years.

“How do you cook an omelette and make a film? It is part of the same person. No one lives a one-layered life,” he reasons.

Now we have veered towards film lyrics. How does he unfailingly catch the pulse of the moment? Again it flows from his serenade to life. And he points to Bengal as the best example of it. “It is the most alive state, with the liveliest of people. I will give an example,” he says.

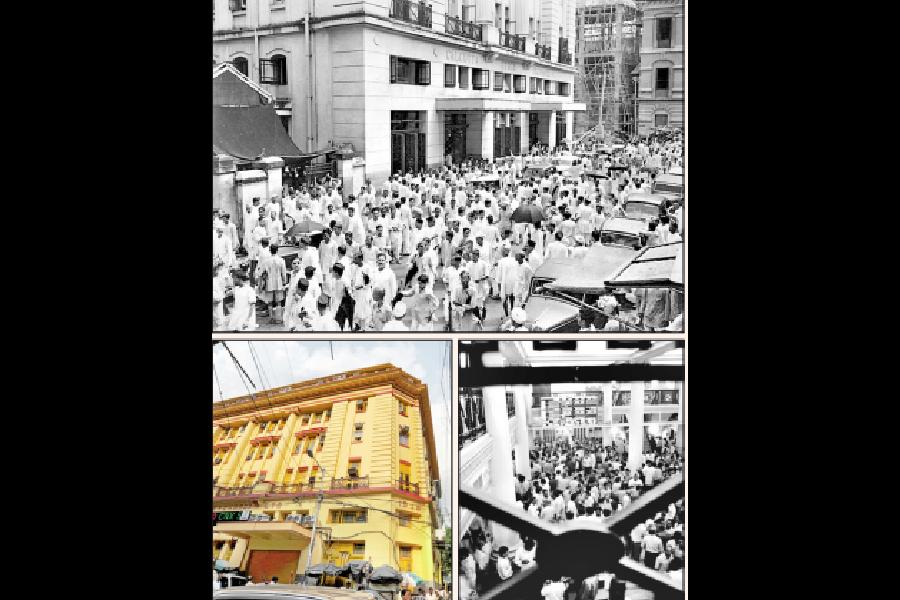

“Woh datun bhi kar rahey hain, road pe baithey huey — he is brushing his teeth, sitting on the roadside,” he narrates, and then bursts into fluent Bangla. “And he says, kothai jachchhen moshai! Ektu maachh kintey jachchhilum. Ei dik diye choley jaan, okhaney boma phutchhe. Ab samajh mein aaya? Main machhi kharidne jaa raha hoon, is taraf bomb phut raha hai, us taraf tram chal rahi hai,” he says. A man is out to buy fish — but there are trams running in one direction, and a bomb going off in another.

Still, he adds, the man has to buy fish. “You have to be alive to life, that’s all,” he says, rounding off his point after a telephone call.

Not only is he undeterred by constant well meaning if completely redundant interruptions by his interviewer, Gulzar has a knack for holding course and the point he is making — returning unflaggingly to almost the very word before the pause. It’s much in the manner of how he neatly rounds off unplanned diversions in life, especially on the road trips that he used to make in trusted Ambassadors. Like the time he bought irresistibly fresh fruit and vegetables while on a trip, and then handed them over to the chowkidar of a mountain rest house, after hoodwinking him into believing he was the guest of a fictitious Major Bakshi. “It’s a method I had practised to get rooms without notice: say the name of any military officer. I am sorry I cheated,” he cracks up again.

Many decades ago, Gulzar came to Mumbai (then Bombay) and worked as a mechanic. It was a job that spared time for literature and writing. “I only knew bearing and steering had the same rhyme! I used to match paint for accident cars. I had a natural knack for preparing that combined colour. For example this sari of yours, there is red and white but also a tint of black in it. I instinctively know and can work it out.”

A poem entitled Gulzar in the new book raises the question about how his name came to be. It’s the name on every document and bank account, except for his passport and income tax papers. “I don’t even like mentioning my full name. I don’t like anyone mentioning it. I don’t like being asked about it either. For this is my identity,” he asserts.

A visitor is announced. As we wind up, one wonders when one will see him return to the director’s chair again. He will, when he reaches saturation point. It’s been nine years since his last film, Hu tu tu, but now the saturation point is near. And the desire is for a small film without a big star cast and commercial compromises. “The scope for small films exists today. I have done 15 hours of filming of Premchand’s works, including Godan, which is a nearly a five-hour film that I have made with Pankaj Kapoor. Others may not agree, but I feel this is filming. I want to bring literature to screen. I want to film 15 hours of Tagore, especially his poem stories. Doordarshan promised but they have not given me the formal letter till date,” he says bluntly.

For now, he is busy with his two collections of poems and a collection of short stories ready to go into print. There is even one novel that is brewing. “I will write it in Urdu, and then make it in English,” he explains.

As for his mastery over Bengali, he had two unmatched gurus. Tagore’s writings, starting with The Gardener, which made the schoolboy want to read the original work, and famed director Bimal Roy, who would give the mechanic his first film break. “Reading came earlier, when I was an assistant. Writing came with my love letters, to my wife (actress Raakhee). The best way of practising Bengali is to fall in love with a Bengali girl and start writing letters to her. So that she’d give me an answer. Amar matribhaasha noy, kintu amar bou bhasha boltey paari ami.” It’s not his mother tongue, but, he reasons, it’s his marital — wife is the word he uses — tongue.

Laughter hangs in the air.